Unplanned Births: Another Outcome of Economic Inequality?

Affluent women are likely to have access to more-reliable forms of birth control, and they're more than three times as likely to have an abortion in the case of an accidental pregnancy.

There are lots of examples of the growing distance between the nation’s haves and have-nots, and the gap between unintended births for the most-affluent women and the least-affluent women is yet another area with a widening economic divide.

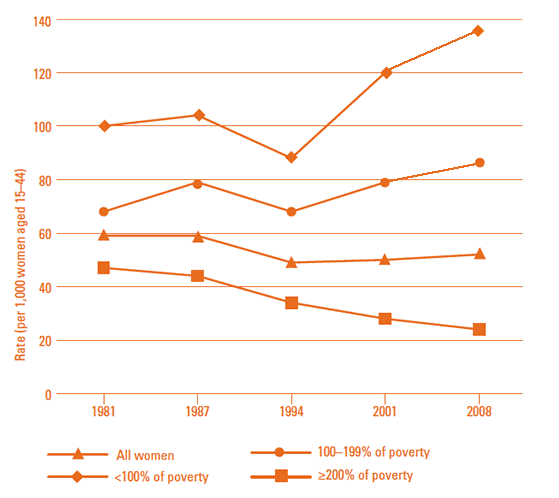

About half of all pregnancies are unplanned, which can make the possibility of an unintended pregnancy seem like not that big of a deal. But the financial impact of unintended pregnancies, and subsequent births, can be significant—particularly for low-income women. Unplanned pregnancies were five times as likely for those at or below the federal poverty level in 2008, according to data from the Guttmacher Institute, a nonprofit that provides research and policy analysis of sexual and reproductive topics. There are economic consequences, for both tax payers and individuals: A 2011 study from the Brookings Institution estimated that healthcare costs for unintended pregnancies and resulting births total about $12 billion in tax-payer dollars each year through government-subsidized medical-care programs like Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Studies have found that these pregnancies can negatively impact educational attainment for mothers. A 2010 paper from Boston University suggests that unplanned pregnancies and births can be detrimental to a woman’s economic status and income, and can reduce the probability of labor-force participation by as much as 25 percent.

A recent study from the Brookings Institution takes a look at women in various economic classes in order to assess what factors play a significant role in unintended births, and their prevention. The paper used data from the National Survey of Family Growth to look at 3,885 single women between the ages of 15 and 44 who said they were not trying to get pregnant. They were separated into five economic groups that measured their proximity to the federal poverty line, which is about $11,770 for a single individual in 2015. Researchers then tried to look at instances of contraceptive use, motivation to have—or prevent having—a child, and abortions in order to parse potential reasons for the differences in unintended births between the economic groups.

What did the researchers find? Well, it’s definitely not about sex. The report found that for every income bracket, just about two-thirds of women had sex in the past year. In fact, women in the highest income bracket reported the highest rate of activity, with 71 percent saying they'd been sexually active. That means that the actual level of sexual activity has little to do with why poorer women are more likely to unintentionally get pregnant and bear children.

It’s also not really about the lack of motivation to prevent pregnancy. “I do think there's something to the idea that there's a bit of a trade off, that the more you have to lose the more determined you are likely to be to use contraception and perhaps access abortion,” says Richard Reeves, one of the study’s co-authors and a senior fellow in economic studies at Brookings. “The danger of that idea is that it might make one a bit complacent about the sort of gaps we find. I think that the evidence is much more strongly on the other side of the equation, that it's access to effective and safe forms of contraception and abortion.”

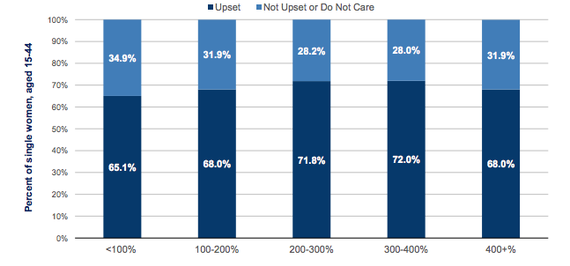

When it comes to the notion that poorer women may be less worried about getting pregnant than their more affluent counterparts (leading them to be more lax in contraception use)—the answer isn’t cut and dry. Across all income groups, the study asked women who were not trying to conceive whether they’d be upset if they did get pregnant. And for each income level the results were pretty much the same, with about one in three women saying they would not be all that upset if they got pregnant, while two-thirds considered such a possibility very upsetting. According to Reeves, intent to get pregnant—or the level of motivation not to—is particularly hard to assess. “You will find some people who are saying, ‘I never want to get pregnant, but I'm not using contraception,’” he says.

Unsurprisingly, the gaps in contraception use were significant between the most and least affluent. Among the wealthiest women, only 11 percent of those who had sex reported not using contraception, for those in the poorest group the rate was more than twice as high. Naturally, that led to a higher rate of pregnancy for lower-income women: 9 percent versus only 2.9 percent for those who had the highest incomes.

The study notes that while contraception coverage is a requirement for many federally-backed insurance plans, abortion (except in the case of rape, incest, or life-threatening emergency) is prohibited by programs that utilize federal funding, like Medicaid—leaving low-income recipients to pay for the procedure with their own money.

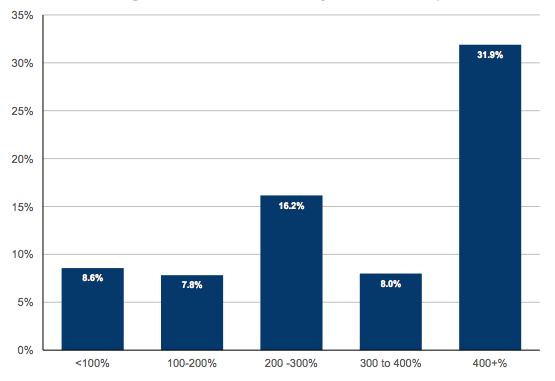

That may help explain what Reeves deemed the most surprising data in the study: The very large gap in abortion rates between the lowest and highest earners. According to the research, when it comes to reports of abortion, the most affluent group was more than three times as likely to have the procedure than the lowest-income group. Of women whose incomes were 400 percent greater than FPL or more, that’s about $47,000, 32 percent reported ending unintended pregnancies through abortion. For the group that falls at or below the poverty line, the figure was only 8.9 percent.

Researchers say that while this divide doesn’t explain the entire gap between the income groups, it is significant. And the figures might help to shed a bit more light on the rates of unintended births for the groups: 7.2 percent for the poorest women and 1.5 percent for the top earners. While there may be many factors at work that help explain the difference in abortion rates, such as different cultural or religious views, the correlation to economic status can’t easily be disregarded.

According to the report, in addition to issues of using federal funds for abortion procedures, there are policies at the state level that can also make obtaining an abortion expensive and difficult. For instance, some private insurers are prohibited from covering the procedure, and tightening regulations are leading to fewer providers in some states, like Texas, which means that those seeking abortion face higher financial burdens due to expenses like travel and absenteeism.

The comparison in childbearing, particularly when it comes to unplanned pregnancies, often brings up the question of whether these discrepancies can be explained by lack of knowledge about reliable contraception and safe abortion options, or if it's the lack of resources that prevents poorer women from gaining access to the most effective methods of birth control and abortion. And the answer seems to be both: More affluent women are more likely to have a better base of knowledge about more effective methods (like IUDs), but they’re also more likely to have the resources to gain access to such forms of birth control which—while cheaper in the long run—generally have higher up-front costs than less reliable options, like condoms or contraceptive/estrogen and progestin pills.

Reeves expects that, in time, the Affordable Care Act will help allay some of those costs. “It would be surprising if there weren't some improvement in levels of contraceptive use among the group we're most concerned about, lower-income women who are the ones who should be helped by ACA,” he says. According to the study, if women who fall below the poverty line had used contraception to the same extent that wealthy women did, their birth rate from unintended pregnancies would fall to 3.4 percent. If they had abortion rates that were similar to those of wealthy women, the birth rate for the group would fall to 4.9 percent.

That signals that though increased availability, and use, of contraception is seemingly the most important factor in bridging the gap between the richest and poorest women, increasing the accessibility to safe, affordable abortions might be part of a comprehensive, effective solution, too.