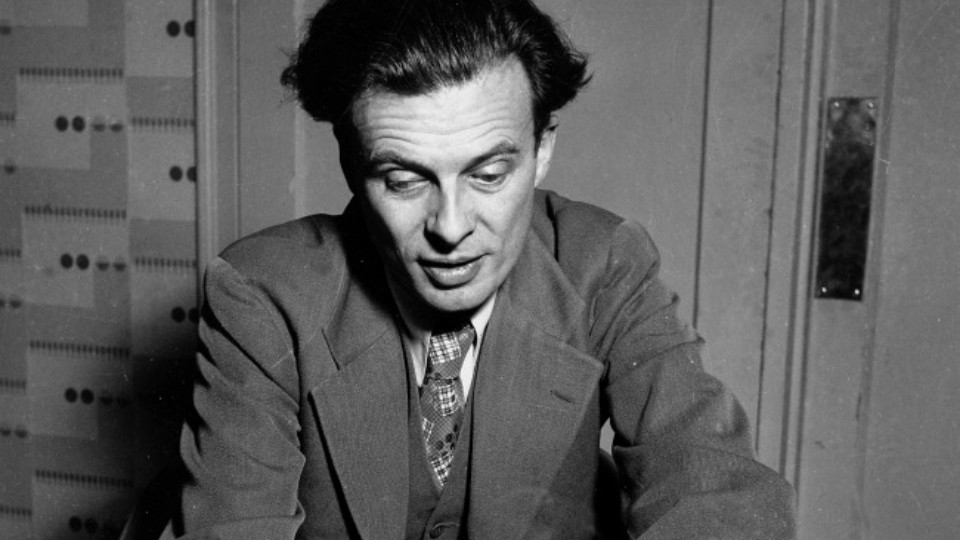

In 1955, Aldous Huxley Wrote This Very Creepy Story for The Atlantic

In honor of the Brave New World author's 119th birthday, an excerpt from "Voices," about a disgruntled orphan's dealings with her high-class relations and a murderous dinner party

In 1955, "Voices," a short story by Brave New World author Aldous Huxley, was published in The Atlantic. Huxley's satire describes one night in the life of Pamela, a disgruntled orphan, and her high-class relations, who (as Pamela likes to remind the reader) have no hope of ever understanding her.

The story begins with a party, hosted by Pamela's aunt. It's all pleasantries until, halfway through the evening, one of the guests, Miss Dillon, starts to hear voices at the dinner table. All of the others listen intently, enraptured. They can hear them, too. When Pamela realizes how seriously her aunt is taking these voices, she decides to try to recreate them -- a game that eventually becomes a murder.

Just before "Voices" appeared in The Atlantic, Huxley -- who would have turned 119 today -- wrote The Doors of Perception, a famous collection of essays about how taking mescaline led him to enlightenment. He wrote this biting satire of upper-class life a year later. Below is an excerpt from "Voices," and you can read the full text here.

There was silence in the lily pool. And now she would refresh her abhorrence of the humans. Keeping to the shadows, Pamela walked over to the house. There they were, behind the plate glass, like things in an aquarium. Mr. Bull was doing the crossword in the London Times. In the yellow sofa beyond the fireplace, Aunt Eleanor was busy on the embroidery of that altar cloth for Bishop Hicks. Beside her sat Alec Pozna with a book, reading aloud. Under the bristles of his mustache those juicy sea anemones that were his lips moved steadily, inaudibly. He turned a page and Pamela had a glimpse of the title: Spiritual Something or Other -- the second word escaped her. She smiled sardonically, remembering that phrase she had read in an article by some Austrian psychoanalyst -- "Menopause Spirituality." In Aunt Eleanor's case it was Menopause Spirituality combined with Senility Spiritualism. You could express it in the form of an equation: -

"Change of Life multiplied by Fear of Death equals

Spiritual Something or Other plus

Give us a Message."

Result: poor old Mr. Bull had to listen to voices, and the unspeakable Pozna (whose personal taste, as she knew, ran to Mickey Spillane and naked girls with bullet holes two inches below the navel) had to spend his evenings reading about Mental Prayer and Religious Experiences.

How peaceful they looked in their aquarium, how domestic, and at the same time how extraordinarily high-class! Like an illustration to a story about Mother's Day -- but Mother's Day at the Vanderbilts'. She made a grimace of disgust and turned back toward the summer house. "Loathsome," she whispered, then touched her face and tried again. "Absolutely loathsome."

This time, it seemed to Pamela, there was a real improvement. Much less breath coming out between the teeth, hardly any movement of the lips. And the throat, the whole face, felt easier, looser, altogether more natural.

She entered the dark cavern of the summerhouse and, feeling all at once very strong and confident, resumed her seat.

"I'll show them!" she said aloud.

"I'll show them," repeated the echo in the vaulted roof.

A wave of heat ran up her spine. There was a prickling inside her ears, and from under her arms there issued a kind of crawling. Like centipedes, like innumerable caterpillars, crawling up her throat, crawling over her breasts -- horrible beyond words and yet one wished it could go on forever. The sensation disappeared as suddenly as it had come. She drew a deep breath and set to work again.

"Loathsome." That was good, she said to herself approvingly, that was very good indeed.

"They're vermin," she went on -- and how absurdly easy it was to get a whistle even on a V! "They're lice, they're bedbugs." And then, "Insect powder!"

She saw a vision of herself spraying Aunt Eleanor with an enormous Flit Gun, sprinkling DDT on Pozna and Mr. Bull. What antics, what a buzzing and a flapping! She laughed aloud. Overhead in the plaster dome, the echoes gasped and cackled. The vision faded, the noise of the merriment died away. Pamela wiped her eyes and prepared to go on with her practicing. What should it be now? More about vermin -- or something else? Suddenly there was a little whisper behind her.

"Not a joke," she seemed to hear; and then, much more distinctly, "I'd really like to kill them."

She started violently, turned and, at the sight of that huge pressure looming out of the darkness above her, was filled for a brief appalling moment with mortal terror. Then she laughed unsteadily. It was only Venus, and she was obviously getting whispers in her brain.

She raised her hands to her face.

"I'd really like to kill them," she repeated.

Under the cool skin not a muscle had stirred; the breath came quietly, evenly, and it came through the nostrils. Incredulous, she tried again.

"Kill them," she whispered, "murder them. Murder them!"

Even at the highest pitch of emphasis her fingers recorded nothing.

"I've made it!" she cried exultantly.

"Made it," said the echo.

And then, in the ensuing silence, she heard the tiny voice again. "Break her neck," it said.

For a moment it was like being on a roller coaster - the bottom falling out of the stomach, the heart rushing up into the throat. Then she remembered a phrase that had been used in her psychology class at UCLA - "Unconscious verbalization" - and was able to smile indulgently at her own terrors. Unconscious verbalization - but of course! And meanwhile, Pamela reminded herself triumphantly, she had made it! She was ready to go and wipe the floor with them, ready to take her revenge, to get some of her own back - at last.