Ferguson's Fortune 500 Company

Why the Missouri city—despite hosting a multinational corporation—relied on municipal fees and fines to extract revenue from its poorest residents

Take a walk along West Florissant Avenue, in Ferguson, Missouri. Head south of the burned-out Quik Trip and the famous McDonalds, south of the intersection with Chambers, south almost to the city limit, to the corner of Ferguson Avenue and West Florissant. There, last August, Emerson Electric announced third-quarter sales of $6.3 billion. Just over half a mile to the northeast, four days later, Officer Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown. The 12 shots fired by Officer Wilson were probably audible in the company lunchroom.

Outwardly, at least, the City of Ferguson would appear to occupy an enviable position. It is home to a Fortune 500 firm. It has successfully revitalized a commercial corridor through its downtown. It hosts an office park filled with corporate tenants. Its coffers should be overflowing with tax dollars.

Instead, the cash-starved municipality relies on its cops and its courts to extract millions in fines and fees from its poorest residents, issuing thousands of citations each year. Those tickets plug a financial hole created by the ways in which the city, the county, and the state have chosen to apportion the costs of public services. A century or more of public-policy choices protect the wallets of largely white business and property owners and pass the bills along to disproportionately black renters and local residents. It's easy to see the drama of a fatal police shooting, but harder to understand the complexities of municipal finances that created many thousands of hostile encounters, one of which turned fatal.

The familiar convention of the true-crime story turns out to be utterly inadequate for describing the social, economic, and legal subjection of black people in Ferguson, or anywhere in America. Understanding this requires looking beyond the 90-second drama to the 90 years of entrenched white supremacy and black disadvantage that preceded it.

To get a sense of what life is like in St. Louis County’s primarily black neighborhoods, one need only look at the extraordinary climate of police harassment that culminated in the death of Michael Brown. Thanks to detailed research and reporting, much of it since the shooting, we now know that over the past two years, 85 percent of traffic stops there involved black motorists, even though the city is only 67 percent black, and that its roads are traveled by a large number of white commuters. After being stopped, black residents were twice as likely to be searched and twice as likely to be arrested as white residents—despite the fact that, in the event of a search, whites proved to be two-thirds more likely to be caught with some sort of contraband. Municipal violations for having an unmowed lawn, or putting out the trash in the wrong place at the wrong time, were issued overwhelmingly to black residents. Ninety-five percent of the citations for the “manner of walking in the roadway” and “failure to comply” were issued to African Americans.

In the same period of time, the city issued over 9,000 warrants for missed court appearances and unpaid (or incompletely paid) fines. According to a report by the Arch City Defenders a non-profit legal advocacy group focused on issues facing St. Louis County’s poor and homeless population, citizens who failed to appear or to pay fines that were “frequently triple their monthly income” were liable to be jailed, sometimes for as long as three weeks. Those with outstanding warrants were rendered ineligible for most forms of public assistance and government-provided social services.

“Ferguson’s law enforcement practices are shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs,” the Justice Department concluded in a March 2015 report on Ferguson’s police department. The report found that the boundary between the fiscal and police functions of the city government of Ferguson had completely broken down. The city manager and the police chief had discussed using tickets to meet revenue benchmarks, and police officers were being evaluated on the basis of their ticket-pushing “productivity.”

In 2013, the city of Ferguson not only had more outstanding arrest warrants per citizen than any other city in Missouri, according to The New York Times. It also harvested $2,635,400 in municipal court fines, which accounted for 20 percent of the city budget. By way of comparison, the nearby middle-class, majority-white community of Kirkwood draws about 10 percent of its revenue from fines; prosperous Ladue, 5 percent. “Absolutely, they don’t want nothing but your money,” the Arch City Defenders’ white paper quotes one defendant as saying. “It’s ridiculous how small municipalities make their lifeline off the blood of the people,” said another. “It’s an ordinance made up for them,” said a third, “It’s not a law. It’s an ordinance.” These ordinances—put in place by a white mayor, city manager, and police chief—generate an unusually large chunk of Ferguson’s revenue. And the excessive fines, combined with the denial of necessary social services and exclusion from public housing, often send residents out on to the streets. Ferguson dramatizes James Baldwin's observation that it is extremely expensive to be poor.

The Department of Justice traced all this back to a lack of training, supervision, and oversight, exacerbated by shoddy record-keeping and clear racial bias. But there’s one question its report didn’t address: How can all this be happening in a community that is home to a Fortune 500 company? Why is the city government filling out its budget with municipal court fines when Emerson Electric is doing $24 billion a year in business out of its headquarters on West Florissant Avenue?

The answers trace back through the history of St. Louis, Missouri—modern American history in extremis. By most measures, St. Louis today is one of the three or four most segregated cities in the country. African Americans can go months at a time without seeing a white person in their neighborhoods—apart, that is, from policemen patrolling their beats, or municipal court judges collecting fines.

The modern history of racial segregation in St. Louis began with the city’s 1916 law establishing separate neighborhoods for blacks and whites. In the 19th century, St. Louis had been one of the nation’s least-segregated cities, but as America prepared to enter the First World War, thousands of blacks from Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas took the Illinois Central northward in search of industrial jobs. During the spring of 1917, 2,000 blacks a week were said to be arriving in St. Louis. That summer, white workingmen rampaged through black neighborhoods in and near the city, killing as many as 200 people and burning the buildings that housed 6,000 more. Black residents of St. Louis concentrated in the downtown area, a pattern that was maintained even after the end of de jure residential segregation (by a 1917 Supreme Court decision).

Through sporadic but consistent violence against black families who moved into white neighborhoods—and various legal mechanisms that stopped short of explicit segregation of neighborhoods but produced the same result—the racial template of St. Louis was maintained over the course of the 20th century. In the decades after World War II, whites moved out to suburbia, but blacks were left behind. Between 1943 and 1960, “mostly white St. Louis County received five times as many [federally guaranteed] FHA loans as did the racially mixed city of St. Louis,” writes the historian and fair-housing advocate George Lipsitz. As whites moved further out from the city, especially westward toward St. Charles County, I-70 was expanded to serve them. In these same years, the city of St. Louis, again with federal support, embarked upon a program of “urban renewal,” bulldozing of some of the city’s oldest black neighborhoods and replacing them with office buildings, to which the increasingly suburbanized middle-class workforce commuted everyday along an ever-expanding number of lanes of federally-funded interstate highway. Longtime St. Louis civil-rights activist Ivory Perry termed these twin programs of urban redevelopment and highway expansion “black removal with white approval.”

Federal law did stipulate that urban-redevelopment projects could only proceed if alternative housing was available to those whose homes were to be destroyed. So federal and city authorities tried to build subsidized housing for St. Louis’s mostly African American displaced population, as well as for the growing number of St. Louis residents seeking affordable housing outside the city limits. But this resettlement only intensified the segregation of an already segregated city. The white population of St. Louis County organized “neighborhood improvement associations,” sponsoring restrictive covenants, running collusive whites-only real estate markets, purchasing empty property, and buying out black homeowners.

Most importantly, they divided the county into a patchwork of new municipalities—“postage-stamp municipalities,” as the urban historian Colin Gordon calls them. Their first acts were generally to pass restrictive zoning codes. The toniest of these new towns completely banned the construction of multi-unit housing, which made it impossible for the government to build federally subsidized housing there. To make the neighborhood even less accessible to poor people, and thus all-too-often black people—the associations sometimes required home lots to be at least one acre in size, effectively placing them off-limits to all but the affluent. The majority of St. Louis’ African Americans took up residence in a gradually expanding corridor running from the downtown area northwestward, towards Ferguson.

Like most of the rest of St. Louis County, mid-century Ferguson was defended by exclusionary zoning codes and whites-only collusion in the real estate market. In the 1960s Ferguson was known as a “sun-down” community: African Americans, mostly from neighboring Kinloch, came in to work in the houses of wealthy whites in Ferguson during the day, but were expected to be out of town by the time the sun set. To this day, the adjacent cities are joined by only two through streets, the Ferguson city line runs down a neutral zone lined on either side with mirror-image three-way intersections. If you have been to St. Louis, you likely landed in Kinloch. Over the last three decades, the vast majority of that city’s black residents have been displaced to accommodate the expansion of Lambert-St. Louis Airport. Over the same period of time, a small number of African American homeowners and a much larger number of African American renters have gradually replaced whites in Ferguson. Ferguson, which was almost entirely white in 1970, today has a black majority.

In 1981, a federal judge in Missouri declared that the “severe” residential segregation of the St. Louis metropolitan area had produced a constitutionally impermissible degree of segregation in the region’s schools. The court tasked the East-West Gateway Government Council and the Missouri Housing Development Commission with developing a plan to desegregate the metropolitan area, but they simply ignored the ruling. At the turn of the 21st century, almost one-half of St. Louis County’s 90-odd municipalities had black populations under 5 percent.

It is not simply the proliferation of municipalities in St. Louis County, nor their segregation, that accounts for the revenue crisis in Ferguson. The city is, after all, home to a Fortune 500 firm. Whatever the history of residential real estate in Ferguson, its commercial properties might be expected to provide plenty of revenue.

But Ferguson is extraordinarily constrained in its ability to pay for the services that its residents require. Municipal tax revenue is limited by the Missouri constitution. In 1980, Representative Mel Hancock—the founder of a group called the Taxpayer Survival Association—wrote an amendment that required any increase of local taxes, licenses, or fees to be approved by a citywide referendum, with very few exceptions. Along with gun-license fees, which are explicitly exempted from the provisions of the “Hancock Amendment,” municipal fines provide Missouri cities with one of the few sources of revenue they can expand without a referendum.

The Hancock Amendment, like similar laws in other states, radically constrains the possibilities of municipal governance. Unable to raise tax rates, many municipal governments have only one tool at their disposal: lowering them. They cannot raise money, but they can give it away.

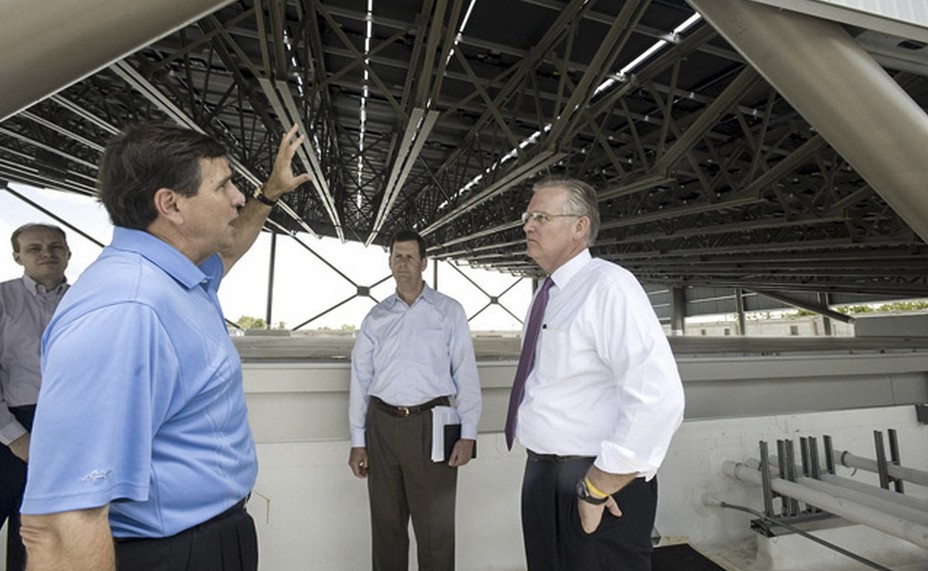

Take Emerson Electric. On July 27, 2009, Emerson opened a brand-new $50 million flagship data center on its Ferguson campus. Subsequent press reports about the data center were filled with numbers: 100 dignitaries at the ribbon cutting, including Missouri Governor Jay Nixon; 35,000 square feet; 550 solar panels; $100,000 in annual energy savings for the company; ability to withstand an 8.0 magnitude earthquake. They noted how many people Emerson employed globally, nationally, and in the St. Louis metropolitan area, although the number of people who might eventually be employed in the new data center itself was hard to find.

In fact, a state-of-the art data center might eventually employ about two dozen people, none of whom were guaranteed to live in (or anywhere near) Ferguson. The economic function of a data center, after all, is to eliminate clerical workers, not to provide them with jobs, and many of its operations can be performed remotely. But the most remarkable missing number of all was the amount of property tax revenue the county and city housing this state-of-the-art building would gain from its construction.

In 2014, the assessed valuation of real and personal property on Emerson’s entire 152-acre, seven-building campus was roughly $15 million. That value has gone up and down over the last five years as Emerson has sold off some buildings and built others, but it has not exceeded $15 million in the period since the data center was completed. So what happened to that brand-new $50 million dollar building?

One explanation would be if Emerson had received a Chapter 353 “local real property tax abatement” to support the construction of the building. For the past 50 years, the St. Louis area has been using these abatements to encourage new development in areas it designates as Enhanced Enterprise Zones. Companies that bring new development there get certain tax incentives. One of these incentives, according to the state, is a 10-year real estate tax abatement. That means a $50 million data center built in one of these zones would be allowed to remain all-but invisible for tax purposes for the first decade of its existence; after that, its appraisal value would be halved for the next 15.

Indeed, in 2008, the St. Louis Economic Development Partnership announced that the data center was being built within a state-designated Enhanced Enterprise Zone. But Emerson denies that it received tax abatements to support the center’s construction. According to company spokesman Mark Polzin, “none of our campus real estate is under abatement.”

Polzin explained to me that Emerson had been eligible for abatements, but it had foregone them out of a concern for fairness. “We never availed ourselves of such ... We felt that our real property had already been being fairly assessed historically by St. Louis County.” According to Emerson, the company is voluntarily paying more than required by law.

It might seem improbable that a corporation would forego tax abatements, to which it was legally entitled, in the name of fairness. But Emerson offered a plausible explanation: Emerson didn’t need the abatement because its taxes were already low enough. At the very least, this raises important questions about the assessment value of property in St. Louis County.

For tax purposes, Emerson’s Ferguson campus is appraised according to its “fair market value.” That means a $50 million dollar solar-powered data center is only worth what another firm would be willing to pay for it. “Our location in Ferguson affects the fair market value of the entire campus,” Polzin explained. By this reasoning, the condition of West Florissant Avenue explains the low valuation of the company’s headquarters.

In fact, the opposite is true: The rock-bottom assessment value of the Ferguson campus helps ensure that West Florissant Avenue remains in its current condition, year after year. It severely limits the tax money Emerson contributes to the Ferguson-Florissant district’s struggling schools (Michael Brown graduated from nearby Normandy High School, a nearly 100 percent African American school that has been operating without state accreditation for the last two years), and to the government of St. Louis County more generally. On the 25 parcels Emerson owns all around St. Louis County, it pays the county $1.3m in property taxes. Ferguson itself receives far less. Even after a 2013 property tax increase (from $0.65 to the state-maximum $1 per $100 of assessed value), Ferguson received an estimated $68,000 in property taxes from the corporate headquarters that occupies 152 acres of its tax base—not even enough to pay the municipal judge and his clerk to hand out the fines and sign the arrest warrants.

St. Louis County doesn’t just assess Emerson a low market value. It then divides that number in three—so its final property value, for tax purposes, ends up being one third of its already low appraised value. In some states, Ferguson would be able to offset this write-down by raising its own percentage tax rate. Voters would even be able to decide which services needed the most help and raise property taxes for specific reasons. But Missouri sets a limit for such levies: $1 per $100 of property. As Joseph Pulitzer wrote of St. Louis during the first Gilded Age, “millions and millions of property in this city escape all taxation.”

Emerson Electric isn’t the only business on Ferguson’s West Florissant Avenue. The street is also home to a number of big box stores including a Home Depot, a Walmart, and a Sam’s Club, located at the city’s northern limit. These companies all came to town in 1997 through something called tax increment financing—known (to the extent it’s known at all) by the acronym TIF. Along with low appraisals and tax abatements, TIF districts are one of Missouri’s principal tools for encouraging new development.

It works like this: A community like Ferguson wants to bring more money into its economy and increase its property values. So it designates a TIF district and borrows money by selling municipal bonds. Those funds are most often used to make the area more attractive to businesses—clearing old buildings, adding roads, upgrading infrastructure. All of this is based on the assumption that the new commercial development will bring a certain amount of revenue—in the form of rising property values on adjacent parcels, increased revenue from sales taxes, and so forth. That revenue will be used to retire the bonds that funded the TIF.

In theory, these incentives don’t cost taxpayers any money. Cities issue these bonds feeling confident that the new businesses will generate more than enough revenue to pay the money back. The problem is that the amount the city must pay each year is locked in at the beginning of the bond issue. If the increased revenue is not as high as expected in any given year, the city finds itself in the red.

Actually, it’s even worse than that. The municipal bonds issued by cities like Ferguson are bundled and sold on a secondary market, in much the same way as the bundled sub-prime mortgages that figured so prominently in the financial crisis of 2008. The purchasers of these bonds then become, in effect, the creditors of the cities that have issued them. Municipal bonds are generally a good investment for multiple reasons. First, under federal law, the interest they pay their holders is tax-exempt. Second, municipal bond holders have the legal status of first-paid creditors: Before a struggling city fixes its roads, or pays for the new park or the school on Main Street, it is legally obligated to pay the investors on Wall Street.

Like any other municipal bond, TIF bonds are ultimately secured by the ability of the issuer to raise revenue: in this case, by Ferguson’s ability to tax its citizens in order to pay off the bonds its has issued. If the revenue falls short of projections, the debt has to be covered by local citizens. Not by the banks—they’re insulated because they have not loaned money directly to the under-performing retailers. And not by the retailers—they’re protected because the city has paid for the capital improvements of the area, limiting their sunk-cost investment in the area. It’s the taxpayers (and fine payers) who have to make up the difference. And in Ferguson, that’s precisely what happened.

The Halls’ Ferry TIF in Ferguson—the one that was used to underwrite the construction of the big box stores on West Florissant Avenue—was originally valued at $8 million. Over the last several years, however, the revenue generated by the TIF district has not been sufficient to cover the bond. The TIF-specific deficits—$43,000 in 2012—had to be covered with taxpayer money.

Not all TIFs fail to match projections. As it happens, there is also a successful TIF in Ferguson. Unfortunately, it demonstrates the ultimate emptiness of the rising tide’s repeated promise to lift all boats. The South Florissant TIF was initiated in 2012 to build multi-use retail and residential space in Ferguson’s downtown area. If it has not been entirely successful in the planning document’s stated goal of establishing Ferguson as a “regional destination,” along the lines of the Delmar Loop shopping and restaurant district, it has nevertheless supported the emergence of the sort of photo-ready pleasantness illustrated in the planning documents. And it is in the black.

So: What’s not to like? Ferguson’s Downtown TIF was self-consciously designed to provide a front door for the city’s subsequent economic development—but it wasn’t designed to improve life for existing residents. Its proponents envisioned an artery of retail and residential development that connects the city (as well as the City of Cool Valley, which was also involved in the planning) to the campus of the University of Missouri-St. Louis and to the industrial development sprawling along I-70. The planning document mentioned that the new district would open downtown Ferguson to the employees of UMSL, Express Scripts, and Emerson. But that document never addressed the disconnection of South Florissant Road from West Florissant Road.

To get from the neighborhood where Michael Brown died to downtown Ferguson, one has to travel a long, undeveloped stretch of Ferguson Avenue and then make a near 180-degree turn under a railroad bridge to merge onto another street that leads to the downtown. There are no sidewalks bordering this stretch of road, and many of those who travel it do so by walking on the shoulder —a notable issue given the risk of being cited for “manner of walking in the roadway” faced by black pedestrians in Ferguson. The “two Fergusons” mentioned by many commentators are effectively connected by a back door.

All of this inverts the whole purpose of funding economic development through taxpayer dollars. Under Missouri laws, TIF district plans are limited to areas that have been designated “blighted” by that municipality. They were designed to bring the benefits of capitalist development to areas that would otherwise be regarded as inhospitable to investment. Along with Chapter 353 tax abatements, which have a similarly framed focus on “blighted” areas, TIF bonds were designed to use the market economy to push forward the not-yet-realized project of racial equality in the United States. In the event, however, these tools have often been turned inside out: used to generalize the risk of investment to the entire population of a city while concentrating their financial benefits in small tracts of development.

The final twist in the story is an extraordinary one. Under the Hancock Amendment, municipalities can raise their sales tax without a local referendum in order to pay for the retirement of TIF bonds. And according to the Ferguson city budget, sales taxes account for the largest share of the city’s revenues. Next come municipal court fines. And after that franchise taxes—taxes on telecommunications, natural gas, and electricity usage. Only after that comes revenue from property taxes.

This means Ferguson extracts more revenue from African American renters seeking to heat their homes in the winter, light them after dark, and talk on their cell phones than it does from those who own the homes themselves. Taken together, these regressive taxes account for almost 60 percent of the city’s revenue. In contrast, property taxes—which are, at least in theory, progressive taxes—account for just under 12 percent. The vast wealth of the city, scarcely taxed at all, is locked up in property that African Americans were prevented from buying for most of its history.

The Ferguson city budget for 2013-2014 noted that the city had not “recovered” from the loss of $1.5 million annually in tax revenue dating back to the financial crisis, which began in St. Louis County in 2006. And yet, instead of making up the shortfall by slashing expenses, the city government responded with renewed spending on, well, the city government. In the last two years, Ferguson built an $8 million fire station, issued bonds to fund the $3.5 million-dollar renovation of the police station, and gave all municipal employees (almost half of whom work for the Police Department) an 8 percent raise. The city’s budget that year also earmarked money to purchase three new Chevrolet Tahoes, presumably including the one Officer Darren Wilson was driving when he confronted Michael Brown and then shot him with one of the 60 brand-new handguns the city purchased in 2013.

So much spending on government infrastructure might have been appropriate in a city that was running a budget surplus, but Ferguson was relying on municipal traffic fines to close the gap between its growing expenditures and its declining revenue. Ferguson had also been dipping into its designated Parks Fund to cover bond payments and operating expenses, to the tune of a million dollars per year. But even this could not cover the renovation of the Ferguson Police Department. The city is using revenue from the Downtown TIF fund for that purpose; what the TIF does not cover will be paid in sales taxes.

The newly elected Ferguson City Council, the first in the city’s recent history to even roughly reflect the city’s racial make-up, will be burdened by this legacy. Which is not to say that the make-up of the city council does not matter. The problems brought about by rock-bottom tax assessments, abatements, and TIF bonds are the same ones facing many municipalities, in Missouri and in other states. They are not unique to Ferguson. They do not make the Ferguson city government especially craven, prone to poor decision-making, or susceptible to self-dealing. As it happens, however, in recent years the Ferguson city government has been all of those things. Faced with only bad choices, the Ferguson city government has repeatedly made dreadful ones.

The story of Emerson Electric’s disappearing data center and the financial malfeasance of the Ferguson city government shows how tools of governance that were intended to harness the power of the market to advance racial equality have often had the opposite effect. In Ferguson, TIF bonds are serviced by regressive taxes and fines levied on black motorists. In Ferguson, commercial real-estate taxes are so low that a Fortune 500 company foregoes tax abatements in the name of fairness, while the city taxes the consumption of ordinary consumers to fill its coffers and those who cannot afford to pay their fines go to jail. In Ferguson, economic development has been collateralized by the citizenry.

When cities like Ferguson come to serve as tax havens or bond-underwriters, they come to depend upon the philanthropic generosity rather than the civic obligations of the corporations located within their limits.

On September 18 of last year, Emerson Electric announced a program of support for early childhood education, jobs for young people, college scholarships for students from surrounding high schools to study engineering at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, and outreach to North County entrepreneurs in need of advice about business plans. Emerson’s announcement concluded with the announcement of a $25 million, 15,000-square-foot addition to the company’s Ferguson campus.

These commitments do represent a substantial improvement. The uprising in Ferguson has led Emerson to refocus its substantial giving in the St. Louis metropolitan area (previously bestowed upon the Zoo, the Botanical Garden, and the Symphony, among others) on the community right outside its gate.

Asked about the company’s response to the uprising in Ferguson, Polzin emphasized “all that Emerson has done in the community over the years.” And he made the point that Emerson has “been there nearly 70 years and has made a decision to remain there. Our role there did not start with those Ferguson initiatives.” This commonsense formulation echoes the familiar axiom that corporations should give back to the community in the form of philanthropy. And Polzin insisted that Emerson deserves credit for its decision to stay in Ferguson. “The real story in our view is not appraisals or incentives,” he said. “It’s loyalty.”

But the point isn’t to belittle Emerson’s good intentions—quite the opposite, in fact. Emerson’s Ferguson initiatives, after all, are substantial and likely to have a consequential effect on the lives of those chosen to receive their benefits. It has been a longtime, and generous, supporter of the United Way. Emerson itself was recently named one of the United States’ Top 100 Corporate Citizens by Business Ethics magazine. The company’s gifts to Ferguson, though, provide the opportunity to reflect more broadly on the idea that philanthropy is a more appropriate form of corporate citizenship than paying taxes.

Emerson’s Ferguson initiatives are the work of a small group of corporate executives who have come to their own conclusions about what the community needs. This is a fundamentally feudal model of corporate citizenship. The vast resources concentrated at the top of our society are distributed according to notions of corporate notions of charity and just desserts, in a pattern that confirms, rather than challenges, the standing order of inequality. For whatever reason, at whatever time, Emerson can decide to stop funding the programs it supports and do something different with its money. The beneficiaries of corporate largess are in thrall to their patrons.

The problem goes deeper than that. The kind of giving Emerson is doing may improve sub-standard education and employment opportunities for African Americans, both of which are products of the city’s long history of racial segregation. But it doesn’t address the underlying structures that created that segregation and maintained it for so long. If a corporation wanted to promote lasting change in Ferguson, it could spend money to address abusive policing throughout the St. Louis metropolitan area, or pay off the outstanding municipal fines of all Ferguson residents. It could fund the construction of affordable multi-unit housing in Crestwood, the 94 percent white West County suburb from which Darren Wilson drove to work on the day he shot Michael Brown. It could buy property along West Florissant Avenue from the real-estate holding companies that own it and make it available on favorable terms to locally owned businesses. It could even ask to have its real estate taxes retroactively recalculated on the basis of the actual rather than “fair-market” value of the buildings on its Ferguson campus.

If these suggestions sound improbable, even absurd, that’s because no company would ever earmark its donations for purposes like these. After all, it’s the job of state and municipal governments to initiate projects like these and raise the revenue needed to make them happen. Corporations shouldn’t have to keep their communities afloat through charitable giving. That’s what taxes are for, and that’s why paying them is typically considered a civic obligation, not an act of generosity.

The death of Michael Brown drew attention to disenfranchised black communities and overzealous policing all across the United States. It also opened the way for another long overdue conversation—about the connections between race and real estate that have become so commonsense as to be able to hide in plain sight.