The 16th-Century Origins of Food Porn

For several hundred years humans have treated food not just as sustenance, but as spectacle.

Thanksgiving is as good a time as any to remember that, for humans, eating is never just about the food. It’s also about ritual, be it the perfectly brewed cup of morning coffee or the annual appearance of grandma’s pumpkin pie. Presentation is what separates us from other animals. We all must eat, but only humans have gone beyond sustenance to make napkin origami and Mayflower centerpieces—and then post pictures of them on the Internet.

Though the contemporary phenomenon of food porn may feel like an Internet-era excess, there’s a long history of different cultures taking part in obnoxious public displays of meals. The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals, currently on display at the Getty Research Institute, considers the history of table decoration and food display in early modern Europe. The underlying message of these centuries-old examples feels echoed in contemporary TV cooking contests like Cake Wars or The Great British Baking Show: So much of eating is about spectatorship, about consuming feats of gastronomy with the eyes more so than the mouth. So lavish Pinterest planning and meticulous Instagram filtering of Thanksgiving dinner isn’t a corruption of the ages-old communal joys of eating—it’s a natural extension of it.

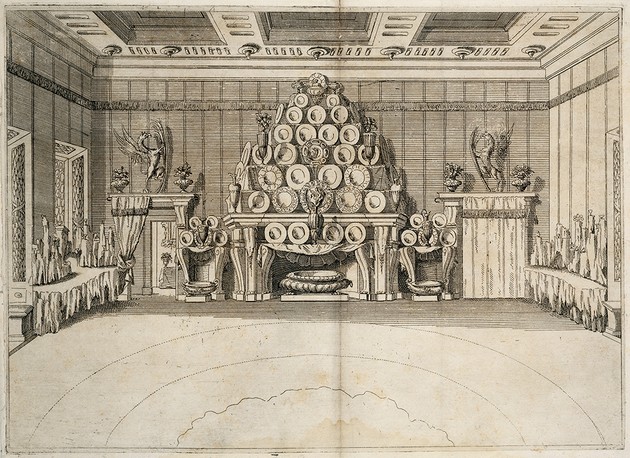

When it comes to party food especially, the sense of sight has always trumped the senses of taste. For Voltaire and other philosophes of the 18th century, taste was not a single sense but the act of discrimination in general, whether applied to painting or pastry. Its opposite was bad taste, or tastelessness. The meat mountains, fruit pyramids, and marzipan castles that graced princely and aristocratic tables from the 16th century onward may have pleased the palate, but they were primarily intended as feasts for the eyes: visibly expensive, fragile, and time-consuming to create, using hard-to-find ingredients like white sugar or out-of-season produce.

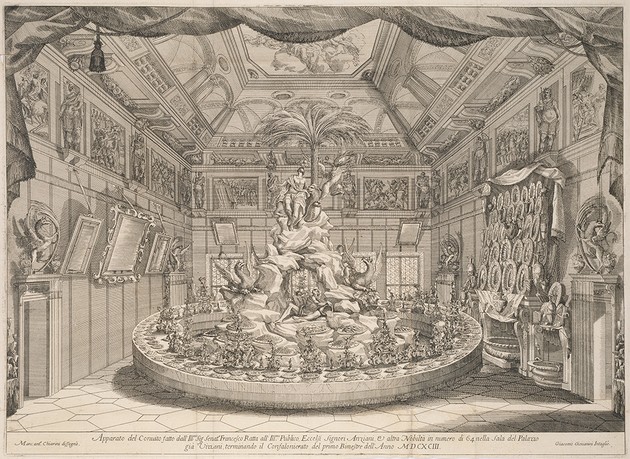

Taking the gluttonous feasts of ancient Rome as their models, Renaissance and baroque festivals—whether public or private—invariably featured beautifully displayed foods in vast quantities. One banquet thrown by the Duke of Newcastle at Windsor in the early 1700s included pickled crawfish, pigeon bisque, lamb roasted in blood, wild boar pie, a drawn and quartered pig, green geese and ducklings, a “stack of pies,” and two pyramids of fruit. Civil occasions were celebrated with temporary architecture and sculpture, including tree-like greased poles hung with fowl and other foods, which revelers could climb for sport and a tasty reward.

These fabulous dishes, decorations, and table settings were meticulously depicted and widely disseminated in mass-produced prints, books, and broadsides, which was at least partly the point of going to all that trouble in the first place. Food was ephemeral, but food porn—the visual culture of food—had a long afterlife in print. As a result, these elaborate entertainments served as propaganda tools. Food festivals were about fostering community spirit, making political statements, displaying wealth, and creating shared memories and histories—the same emotional appetites that drive today’s competitive foodie culture. Though they may depict things like 60-foot-high centerpieces of molded sugar and triumphal arches of bread and cheese, these centuries-old books and images have the same kind of half-instructive, half-smug tone you’d find in the pages of Martha Stewart Living.

Because these monuments were more about spectacle, they may have been technically edible, but they weren’t always eaten. Roasted peacocks and swans looked stunning on a banquet table, but they didn’t taste especially good. The nursery rhyme about “four and 20 blackbirds baked in a pie” isn’t just doggerel; a pie cut open to reveal live blackbirds who sing on cue was precisely the sort of culinary performance art that early modern partygoers expected. What the Germans called “Schau-Essen”—literally “show food”—was usually placed on the table as the grand finale to a meal, once everyone was already full, and not intended to be eaten.

The popularity of edible table decorations beginning in the late-15th century was closely linked to the growing availability of sugar, imported to Europe from Africa and the Caribbean. On a state visit to Venice in 1574, Henry III sat down to a lavish “sugar course” and lifted his napkin, only to have it break apart in his hand. The king was amused to discover that not only the napkins but all the crockery and cutlery were crafted from sugar. These sugar courses were not just sweet nothings; properly deployed, they flattered distinguished guests while simultaneously advertising the host’s wealth, munificence, and good taste, in all its connotations.

In the 18th century, sugar courses became less common but even more ornate, covering whole banquet tables in sugar sculptures depicting formal gardens populated by classical temples and statuary, or illustrating stories from literature or the theatre, staged on mirrored trays to reflect light and reveal hidden details. “All columns, cornices and fixtures, all statues and figures ... and everything visible are cast entirely from sugar,” Julius Bernhard von Rohr marveled in 1729. But sugar was no longer the luxury item it had once been; increasingly, even the middle classes sweetened their tea and coffee with it. Edible dessert table decorations—already virtually indigestible—were replaced by a more permanent doppelganger, biscuit porcelain pieces, which resembled sugar sculptures but cost more, and lasted longer.

These images of ancien régime extravagance can’t help bringing to mind that most modern of party planning tools, Pinterest. Today, instead of royal birthdays and religious festivals, we stage-manage elaborate entertainment to celebrate big episodes of favorite TV shows, divorces, or baby-gender announcements; instead of larger-than-life sugar sculptures and fountains flowing with wine, we impress our friends with artisanal tailgating and ridiculously over-the-top children’s birthday parties. Having a few people over to watch the big game no longer means chips and dips but an Instagram-worthy spread of mini chicken-and-waffle sliders, Nutter Butter referees, and football-shaped pumpernickel sandwiches, the stitches piped on in mayo (but only at the last minute, lest they soak into the bread). When every meal is on camera, all food is porn.

The spirit of early modern Europe’s wealthiest lives on in the foodie culture of today. It’s there in the audacity of the edible helium balloon served by Chicago’s Alinea restaurant, in the $1000 Golden Opulence Sundae at New York’s Serendipity 3, in the $30 million, gem-encrusted cake made for a socialite on the show Cake Boss. And on a more relatable level, we may cringe at the idea of baking live blackbirds in a pie, but is it really any more offensive (or labor intensive) than a turducken? Whether on television or on the table, festive food is all about the big reveal.