A New Age of Animation

Many animated series in the U.S. are hand-drawn in South Korea, but the country’s recent transition to digital tools could spur a transformation in American television.

Animated sitcoms have long offered sharp insight into American culture. The Simpsons is so astute that, 16 years ago, the show predicted Donald Trump’s run for president. A running joke on Bob’s Burgers revolves around the “Burger of the Day,” with past entries including the “Sweet Home Avocado Burger” and “Mission A-Corn-Plished Burger.” The Boondocks follows a black family as they adjust to life in a mostly white suburb. Family Guy—a subversive spin on a family with 2.5 children and a dog living in Rhode Island—has lampooned everything from the legalization of marijuana to summer camp.

Although these primetime series appear as American as apple pie, and are conceptualized and written in the U.S., the bulk of their animation is done in South Korea. Animation requires 12 frames for every second of airtime. Korean studios take the voice recordings and the storyboards, and their artists draw out each frame—on paper. They start with characters’ key poses, then do the “in-betweening,” or the painstaking process of crafting incremental micro-movements so the motion looks smooth. Korean animators can draw 240 pages for a single 20-second scene, and around 7,000 drawings per half-hour episode.

Outsourcing has its benefits—largely, that it lowers costs. But the two-country system has led to a technical divide that slows things down. While studios in the U.S. moved to using digital animation tools years ago, Korean studios have been slower to make the shift. Because they still mostly work on paper, each finished frame has to be scanned individually for delivery to American studios. If what’s drawn on the page doesn’t match what the show’s creators imagined, revisions can take a week or more—entire scenes have to be thrown out and reworked from scratch. But one company is finally helping Korean studios go fully digital, and the impact for animation in the U.S. could be significant.

The process of outsourcing animation began in the 1970s, when the three major American networks—ABC, CBS and NBC—aired Saturday morning cartoons like Scooby-Doo and Fat Albert. These shows were hugely popular, and American production studios struggled to meet the demand for more episodes. “They had no other choice but to outsource production,” says Nelson Shin, the founder of Seoul’s AKOM Production, which has animated The Simpsons for more than 25 years. Korean artists proved themselves to be technically astute and fast, and by the 1990s, Animation World Magazine estimated that 30 percent of the world’s animation production was done in Korea.

Today, the Korean animation industry is a complex web of around 120 studios, creating work for Fox, DreamWorks, Nickelodeon, and the Cartoon Network. “Not many people know about the close relationship between Korean and American animation production,” says Shin. The only tell, he says, comes if you pay close attention to a show’s credits.

This configuration has interesting ramifications. For one thing, there’s a cultural divide between the people drawing the series and the people who dreamed them up (not to mention the people who watch them). Animated sitcoms aren’t just American, they’re hyper-American—pointing out the absurdities of U.S. culture is their reason to exist. Any American who’s ever watched a K-Pop video and felt confused by the artistic choices on display might empathize with how Korean animators sometimes feel about the American shows they’re creating.

Joel Kuwahara is the co-founder of Bento Box Entertainment, the Los Angeles-based studio that produces Bob’s Burgers. He notes the cultural complexity of the two-country system. “It can be hard to communicate precisely what we want,” he says. “It can be acting nuances—or dance moves. How do you articulate a particular dance move that we want to animate to a Korean studio?”

The fix: American production companies employ “overseas animation directors” to work within Korean studios and check animations before they’re sent back to the United States. Philippe Angeles has served in this role for years, currently for Bob’s Burgers, and sees himself as a bridge between the two cultures. “We have a different perception of humor. Something very funny to us might not be funny to them,” he says. “We have a different approach to everything, including body language and expressions.”

Even a simple movement can become complex. “Say we want to just adjust an eyebrow by five pixels,” says Kuwahara. “The paper way, we have to explain where that eyebrow should be, that note will get sent to Korea, then an animator has to get a new sheet of paper and draw it, and that piece of paper has to be scanned and recomposited.”

Kuwahara knew this convoluted revision process was crazy. A former producer on The Simpsons, he co-founded Bento Box in 2009 with a vision for bringing Korean animation into the 21st century. He reached out to Toon Boom, makers of the animation-industry standard software, Harmony, and the companies spent two years collaborating to improve functionality for Korean animators. From there, Kuwahara scheduled meetings with the heads of Korean animation studios, to show them how an all-digital pipeline would simplify their process and allow American and Korean studios to work together more seamlessly.

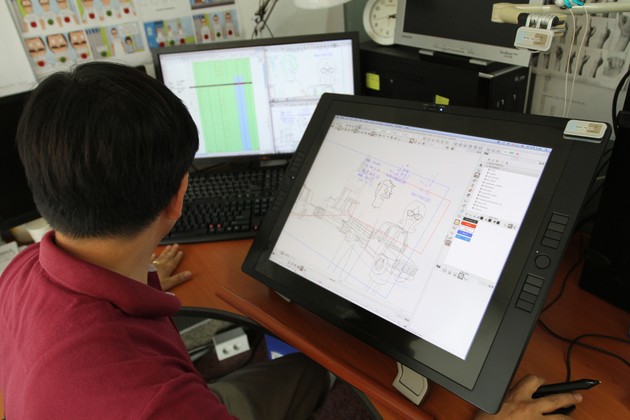

Kuwahara showed them how drawing on-screen would allow in-betweeners to create consistent line quality every time. He showed them how going fully digital would ease the revision process, making it so that anyone—in Korea or the U.S.—could open a file and make adjustments. He demonstrated how the eyebrow problem could be fixed in mere seconds.

Still, in meeting after meeting, Kuwahara got the same response: Korean studio owners couldn’t justify the expense, given that most clients weren’t asking for the change. “How do you move a big show like The Simpsons into a different production pipeline?” Kuwahara says. “When you’ve done so many episodes a particular way, it’s tough to adjust all the moving parts.”

Korean studios have faced technological change before. Animators here—like their American animation predecessors—once drew on translucent cells, which were then painted by hand. In the 1990s, Korean studios moved to doing “ink and paint” digitally—they started scanning line drawings and coloring them via software. Today, changing a color in a scene means a few clicks rather than redrawing everything. “When people were on paint, it was like, ‘Why should we stop painting?’’’ says Kuwahara. “Now, no one can conceptualize having to go back on paint.”

Eventually, Yeson Entertainment—where Angeles works—became the first Korean studio to say “yes” to an all-digital pipeline, to work on Bob’s Burgers. The show’s first season included cutout animation—the cheaper provenance of shows like South Park—but Bento Box had the budget to make season two fully hand-drawn. Yet, Angeles stresses that switching was a risk. “I cannot emphasize enough how much courage it took when Yeson accepted,” Angeles says. “A lot of people were looking at us in the distance and they didn’t think we were going to make it. I think some hoped it would fail.”

Not every animator adores all-digital animation. Some point out that it can have a homogenizing effect, and one told me bluntly, “Pencils don’t crash on you.” And as Bento Box began training Yeson’s animators in using Harmony, the learning curve proved steep. “I always know that on day one, I’m going to get 80-90 percent resistance,” says Kuwahara. “At the end of week one, I’m going to get every excuse under the sun for why the decision to use this software is wrong.” But somewhere in week two, he says, there’s an a-ha moment.

Angeles says it takes about 12 weeks for an animator to get back up to speed after switching. It’s a time investment, but the new workflow, he says, has “changed my life.” Revisions are now easy, which gives him more time to focus on the overall artistry. “We can add more quality,” he says. “For example, shadows. Now if the creator or director wants them a little darker, it’s a click of a mouse. That’s all it takes.”

In January, Fox premiered Bordertown, a series about a disgruntled border-patrol agent and his Mexican neighbor, produced by Bento Box and Seth McFarlane. Two Korean studios, including Hanho Heung-Up, switched to an all-digital workflow to animate the show. The owner Seok-Ki Kim is a 30-year animation veteran who worked on G.I. Joe in the 1980s, and who wanted to work on Bordertown for a simple reason: He loved the premise. Despite living in Seoul, he relates to the culture clash along the U.S.-Mexico border, and sees universality poking through the specificity. “It’s about the minority and how they interact with the majority,” he says.

Many who work inside Korean animation studios sense a tipping point nearing. Kuwahara knows of five Korean studios who’ve now gone all-digital, and Toon Boom estimates that 30 percent of their Korean customers have either tested or are moving toward an all-digital pipeline. Even Shin of The Simpsons says he is “thinking about” fully digitizing.

“The chain reaction has started,” says Angeles. “Eight years in the future, the industry in Seoul will look radically different.”

For Korean animators, this change could mean a different kind of work life — perhaps one characterized by fewer late nights, and an increased ability to work from home. Beyond that, Kuwahara thinks the change could influence who wants to become an animator. The paper method seems oddly out of step in a city like Seoul where Internet access fully permeates life. Many young people are more interested in working in video games or CGI.

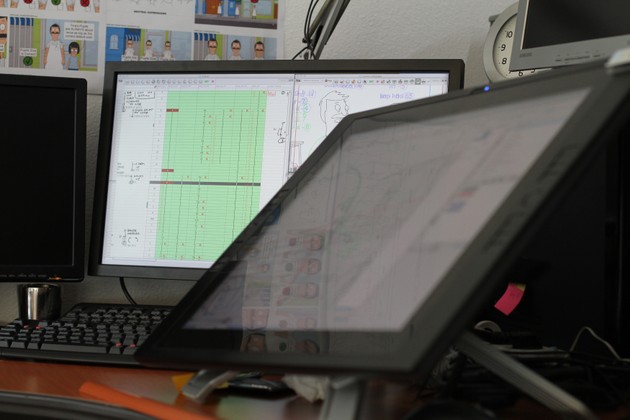

“When they think of 2D animation, they think of someone sitting behind an animation desk with a stack of paper and pencils. It looks nostalgic,” says Kuwahara. “I see the faces of college students when we give tours of our process. They see the multi-screens on an artist’s desk, and they’re just like, ‘Wow.’”

As the industry shifts, American viewers might not actively notice the changes. But changes there will be. Because the all-digital pipeline makes producing animated television more streamlined, the shift could mean a greater number of animated sitcoms dotting the primetime landscape. American networks want animated series that feel “iconic,” says Kuwahara. He sees the fully digitized process letting show creators dream vividly, and giving production companies the tools to deliver on series that feel bold and unique.

Fox announced this week that Bordertown has been cancelled. Still, the show may well represent what American viewers will see more of Korean animation goes fully digital. Bordertown’s unique feel comes from its fast pace and visual complexity. While many jokes land via punch lines, even more pop into view, embedded in rich backgrounds. Kuwahara points to the title sequence. “It’s one of the most complicated main titles I’ve ever worked on,” he says. “The creator of the show had a million ideas.”

The 25-second sequence begins with the show’s characters floating in a storm cloud. The field of vision snaps back, and the audience flies over a desert landscape, chasing the cloud as it rains down on buildings and people to form a town. The show’s main character, Bud Buckwald, lands in the back of a pickup truck, and the shot follows him to an empty lot, where his family and their next-door neighbors, the Gonzalezes, fall into place. A hand enters the frame—“almost like a hand of God,” says Kuwahara—and bumps the ground, before placing the series name in the sky.

The frenetic sequence took weeks to make. Animators in Korea worked on the characters while animators in Los Angeles worked on the special effects—all looping their work together into the same digital file. The sequence could have been done the old-fashioned way, but it would have taken longer and the pieces would have been hard to fit together. The speed is great, says Kuwahara, but the real triumph is audiences getting the uncompromised vision.

This, to Angeles, is the key point. “[Going fully digital] has allowed us to be more daring,” he says.

Bob’s Burgers airs its 100th episode on May 22. Perhaps one of the reasons for its success is that its makers have more tools to experiment. Take the episode “Speakeasy Rider,” which aired in January 2015. The show’s young siblings—Tina, Gene, and Louise—join a go-kart league. It’s difficult to animate moving vehicles by hand, so the scenes were created by pulling CG models into Harmony for animators to use as a guide. The result: Go-carts zoom around a track, slide sideways, and pass each other with realistic perspective. The viewer ends up in the driver’s seat, backgrounds gliding to and fro over the steering wheel, and landmarks shifting in the rear windshield.

Angeles notes that, as the move toward an all-digital pipeline in Korea advances, American viewers will see series of higher quality. Shows will have more consistent line strokes, more customized colors, more ambitious camera movement, more creative scenes.

“They might not see the difference,” he says, “but they will feel it.”