How Ghana's Gory, Gaudy Movie Posters Became High Art

In the ’80s and ’90s, artists were charged with making films seem as lurid and enticing as possible, regardless of plot.

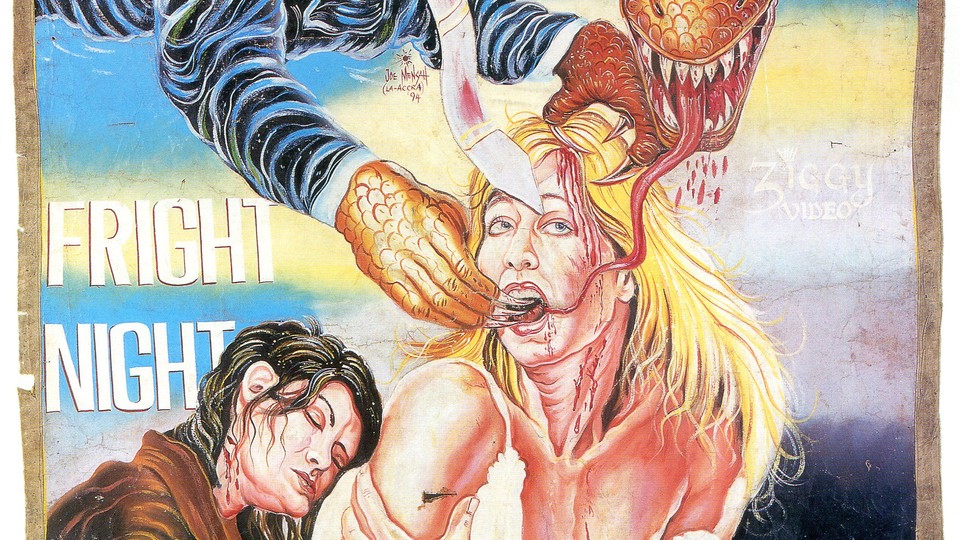

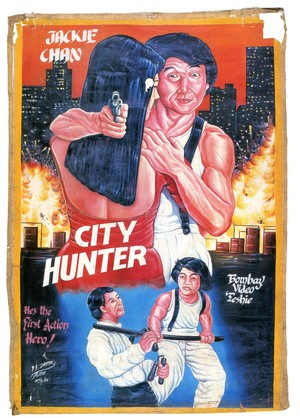

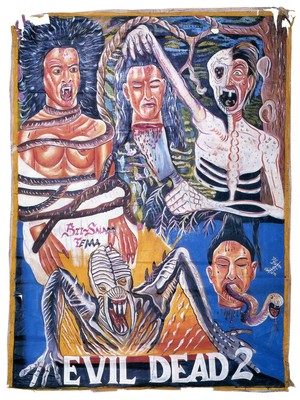

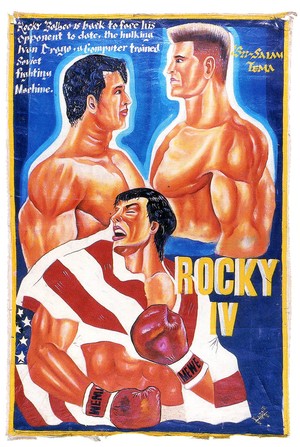

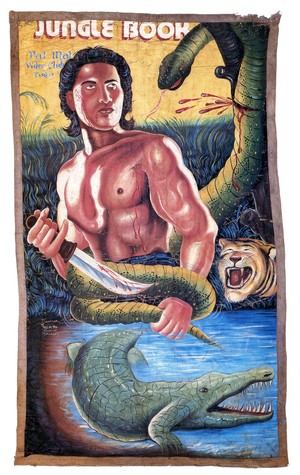

When Frank Armah began painting posters for Ghanaian movie theaters in the mid-1980s, he was given a clear mandate: Sell as many tickets as possible. If the movie was gory, the poster should be gorier (skulls, blood, skulls dripping blood). If it was sexy, make the poster sexier (breasts, lots of them, ideally at least watermelon-sized). And when in doubt, throw in a fish. Or don’t you remember the human-sized red fish lunging for James Bond in The Spy Who Loved Me?

“The goal was to get people excited, curious, to make them want to see more,” he says. And if the movie they saw ended up surprisingly light on man-eating fish and giant breasts? So be it. “Often we hadn’t even seen the movies, so these posters were based on our imaginations,” he says. “Sometimes the poster ended up speaking louder than the movie.”

In fact, many of the posters painted by Armah and other Ghanaian artists in the 1980s and ’90s have gone on to achieve a fame almost entirely detached from the films they depicted. Today, they’re collectors’ items, hanging in art galleries in the U.S. and Europe and frequently retailing for upwards of $2,000 a pop. And the most successful of the artists—who once churned out dozens of images a year on razor-thin margins for local cinemas—now make their wares on demand for their cult following of international fans.

“World cinema is a lingua franca we all understand,” says Ernie Wolfe, a Los Angeles art dealer and collector who first noted the unusual artistry of Ghana’s cinema advertisements while traveling in the country in 1990. He now collects the posters. “These posters appeal to people because [they] invite this really incredible dialogue—a comparison between what you know of a film and how the painter imagined it. And they’re also just really good art.”

That, Wolfe says, is the kernel of the posters’ enduring mass appeal—they represent a sliver of cinema history that is now irretrievable, before the world-flattening effects of technology and globalization rendered it all but impossible to advertise a film in anything but the most literal terms. For nearly two decades in Ghana, the concepts behind the world’s most famous movies mixed freely with the imaginations of its most talented painters, creating a gaudy, gory, glittery tradition of pop art like none other in the world.

* * *

Outside the workshop of the painter Daniel Anum Jasper in the Accra neighborhood of Teshie, a dusty stretch of road is crammed with a shifting band of hawkers roaming the streets with veritable mobile supermarkets balanced on their heads: everything from air fresheners and donuts to toddler-sized blue jeans and inflatable swimming pools. Among their most valuable wares, however, are stacks of bootleg DVDs.

To the American eye, the selection is wildly global—there are American rom-coms and Bollywood love stories alongside low-budget Nigerian thrillers and east Asian martial-arts movies. But as Jasper is quick to point out, Ghanaians have long been omnivorous consumers of the world’s cinema. As far back as his childhood in the 1970s, urban Ghanaians were enjoying Hollywood, Bollywood, and Nollywood with equal enthusiasm in the city’s many cinemas.

“As a kid, we loved movies,” he says. “We went all the time.”

Outside of major cities, films were a far rarer commodity. Many villages lacked electricity, let alone the set up for a movie theater. But it didn’t take long for a few enterprising businesspeople—a population West Africa seems to possess in unusual abundance—to come up with a solution. They bought diesel generators, movie projectors, and VCRs, tossed them in the backs of trucks, and headed out to the hinterlands with their mobile cinemas in tow.

And along with Accra cinema owners, they soon began hiring local artists like Jasper—who in the mid 1980s was a young sign painter in Teshie—to paint posters advertising their wares.

“Sometimes they showed me the cassette of the movie, other times they would just describe the story,” he says. And from there, he was off, sketching his designs on old flour sacks and supplementing images of the film’s main actors with fires, guns, snakes, hacked-apart limbs, and laser beams. Nothing was too outlandish. “Just something to capture people,” he says.

Take the poster for the 1987 Arnold Schwarzenegger film Predator. In the original, a dirt-smeared Schwarzenegger occupies the entire frame, his gun and sullen gaze aimed squarely at an enemy just off-screen. In the Ghanaian version, however, Schwarzenegger is merely a sideshow to a hairy, horned monster, his green talons wrapped around the body of what looks like a naked Playboy model in the throes of ecstasy.

Other posters, meanwhile, seem to operate like a game of Pictionary—providing images that would certainly help you guess the title of a movie, if not, perhaps its actual content. There’s the Ghanaian take on Stephen King’s Cujo the Killer Dog, for instance—a sheepish suburban spaniel with a trickle of blood running down his snout. And the figure looming most largely in the poster for Cat Woman is, well, a cat with a forked tongue of course.

For Jasper and others, it was obvious from the start that this wasn’t exactly the most lucrative of jobs. A good poster, he says, one that really made a splash, took at least three days to paint, and the cinema owners could never afford to pay much. For a quick buck, it was far easier to paint road signs or billboards.

“That one of the ways you know this was an artistic movement—these posters were always far more beautiful and detailed than they needed to be to fulfill their practical function,” says Wolfe, who has published images of more than 500 of the posters in two coffee table books, Extreme Canvas and Extreme Canvas II.

Indeed, much of the contemporary art in the region, he points out, doubles as something practical, from richly detailed barbershop signs to coffins sculpted in the shape of pencils, paintbrushes, and even soccer cleats to carry off the dead in style. In every case, he says, there’s an attention to craft that clearly transcends the object’s purported practical value.

“I can look at these posters from across a room and tell immediately who painted what—these guys had distinctive styles and competed against each other to stand out and be better,” Wolfe says. “That was how they got jobs, but also how they developed their reputations.”

That the poster-making tradition ever took off at all, however, also owes a great deal to a strange quirk of Ghanaian history. During the military dictatorships of the 1970s and ’80s, restrictive laws cut off the importation of the large-scale offset printing presses popular for poster making elsewhere in the world. So even though the necessary technology had been available as close by as Nigeria, Ghanaians continued to hand-craft movie posters and other signage well into the 1990s, creating a unique space for a generation of artists to develop their talents.

“For me, they demonstrate what was possible before this radical shift towards technology,” says Joseph Oduro-Frimpong, a Ghanaian sociologist and movie-poster collector.

Unfortunately, it couldn’t last. By the turn of the millennium, in Ghana as elsewhere, it was far easier and cheaper to mass-produce posters than to have them painted by hand. Ironically, the poster painters’ extra attention to detail was part of their downfall. They had always worked too slowly. They had always cared too much. And it was far more difficult to sell an ethnically ambiguous James Bond with a red fish sidekick when the viewer showed up to the cinema already steeped in the international pop culture—celebrity photos, movie trailers—that traversed the globe via the newly minted World Wide Web.

* * *

Still, Jasper and at least a few of his fellow artists might be getting a second chance. Since the mid-2000s, Ghanaian poster artists have received a steady flow of international attention, including interest from the makers of the movies the original posters were sketched for. When the director Clive Barker saw the Ghanaian version of the poster for his 1988 horror flick, Hellraiser III—featuring a non-existent scene in which the lead character swallows an unfortunate victim whole—he became an immediate fan.

“There is, needless to say, something immensely satisfying about seeing an image you originated … reworked and rediscovered this way,” he wrote in a blurb for one of Wolfe’s books.

Meanwhile, would-be customers from overseas began contacting Jasper and others, eager to have their own versions of the day’s popular films on canvas. (A struggling video store in Chicago, for instance, commissioned an improbably bloody retelling of Mrs. Doubtfire.)

Today, Jasper and Armah both paint posters and ship them on demand. But the transactions, these days, are coldly economical—sapped of the rivalry and innovation that once made the poster-making industry so unique and lively. “If you want to make your living as an artist, you paint whatever people ask you for,” Jasper says bluntly.

Anyway, he says, part of the magic of the old days was that the posters had lives of their own, completely outside the films they depicted. Now, he Google image searches movie posters he’s hired to reproduce in one of Teshie’s Internet cafes.

For Wolfe, the original charm of the posters he encountered in the ’90s lay in how wildly unself-conscious they were—vivid, ostentatious, and strangely beautiful without a flicker of care as to how the outside world would perceive them. In an era where an increasing number of African painters train overseas and paint largely for western audiences, Ghana’s golden age of movie posters points to an era when it was possible to paint without wondering who was watching.

“They were absolutely fearless in their interpretations of plots and events,” he says. “Now the world is a small, flat place.”