The U.S. Supreme Court Walks a Fine Line on Race

A 5-4 decision limits the use of policies that cause segregation, but not segregation itself.

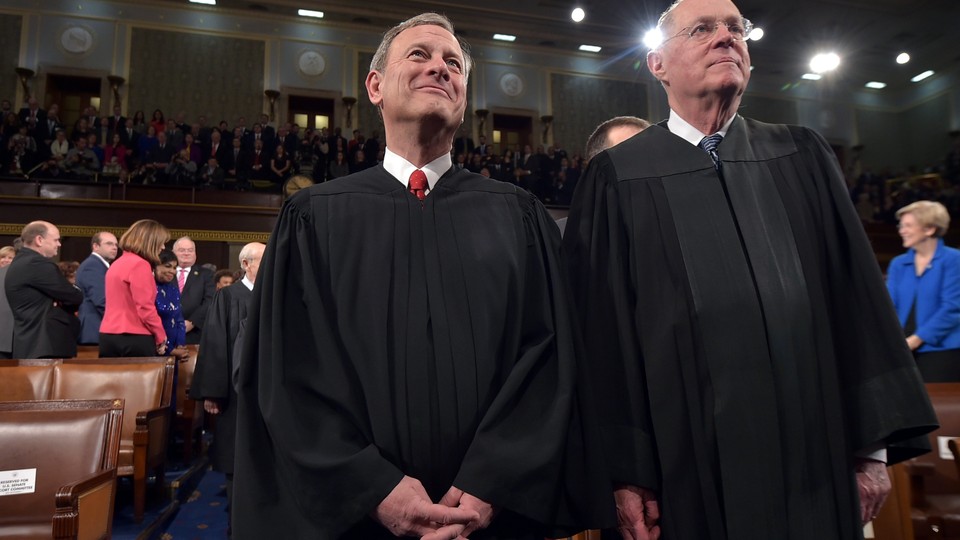

The Roberts court has had a lot to say about race. It upheld a Michigan ban on affirmative action for university admissions. It struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, arguing that laws addressing the South’s history of racial discrimination were no longer needed. And it nixed voluntary school-desegregation plans that assign students to schools based on racial quotas.

But the court isn’t blind to the effects that decades of discrimination have had on minorities in this country, as became evident Thursday in its 5-4 decision upholding the “disparate-impact” standard of the Fair Housing Act. That standard allows groups to challenge policies that adversely affect minorities, that, for instance, segregate them in high-poverty, high-crime areas of town. Discrimination doesn’t have to be intentional to be unlawful, the court found.

The case was brought by a Dallas-area non-profit, the Inclusive Communities Project, who argued that the Texas Department of Housing and Community Development had approved housing projects predominantly in high-poverty, minority neighborhoods, a policy that had a “disparate impact” on minorities.

The court agreed, writing that disparate-impact claims have proven useful across the country as a way to combat discrimination that has gotten more subtle since the civil-rights era.

Recognizing disparate-impact liability “permits plaintiffs to counteract unconscious prejudices and disguised animus that escape easy classification as disparate treatment,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, in his opinion for the majority. “Disparate-impact liability may prevent segregated housing patterns that might otherwise result from covert and illicit stereotyping.”

The decision was hailed as a win for civil-rights groups, who had argued that disparate-impact claims are the only way to remedy policies that lead to segregation. But it’s important to note that in this decision, the Supreme Court did not approve compulsory integration. In fact, Kennedy’s opinion specifically warns that policies that integrate housing by race quotas are unconstitutional. Instead, the ruling allows groups to continue to challenge the policies that perpetuate segregation, not segregation itself. The distinction may seem small, but it’s important.

ons that have discriminatory impact,” he said.

As I’ve detailed before, the Inclusive Communities Project argued that the points system Texas formerly used to award low-income-housing tax credits to developers favored building projects in high-poverty areas, isolating poor, minority residents in poor, minority neighborhoods. Social scientists say this makes it more difficult for families to escape poverty and to access the resources, such as good schools and jobs, that they would be available in more affluent areas. But under this ruling, a remedy could not simply order the state to build housing projects for minorities in white areas. Instead, a remedy would have to address the policy guiding how tax credits are assigned, taking into account whether that policy as a whole perpetuates segregation. (In 2010, for instance, a District Court ordered Texas to change how it awards tax credits, which it did.)

When courts find remedies in disparate-impact cases, they should “concentrate on the elimination of the offending practice” that leads to arbitrary racial discrimination, Kennedy writes.

In that way, the decision is in line with the Parents Involved decision about school segregation, said Andrew Scherer, the policy director of the Impact Center for Public Interest Law at New York Law School.

“Inclusive Communities and Parents Involved are not about quotas, they are about the obligation to be aware of the consequences of government and private action, and to avoid acti

The remedy that Texas came up with back in 2010 as a result of the lawsuit was race-neutral, a giddy Mike Daniel, the lawyer for the Inclusive Community Project, told me on the phone.

“This says you have to give equal points to projects located in high income and low-poverty areas,” he said. “There’s no race there. And it did, in fact, work.”

After the state changed its formula, developers proposing projects in high-opportunity areas received more points than they had before. Since then, more developers have built tax-credit developments in the suburbs, Betsy Julian, the executive director of Inclusive Communities, told me.

Fearing legal action, Dallas-area cities with predominately white populations, including Frisco and McKinney, also agreed to build affordable properties in the last few years. Though Inclusive Communities had to fight “tooth and nail” to get these projects built, “what you’ll see is a lot of the fears that people had with regards to the effect of the project on the value of their homes didn’t really have merit,” Julian said. One of the projects built because of an Inclusive Communities is in Sunnyvale, a Texas town that banned multifamily units and fought multiple court orders to allow them. D Magazine recently called it “the whitest town in north Texas.”

Still, Justices Thomas, Scalia, Alito, and Roberts heartily dissent with the decision. In a separate opinion, Justice Thomas reminds the court that racial imbalances don’t always disfavor minorities—Chinese were minorities in Malaysia, for instance, but still controlled the industry in that nation.

Furthermore, “This Court has repeatedly confirmed that ‘racial balancing’ by state actors is patently unconstitutional,’” Thomas writes.

But the majority does not see the policies behind Inclusive Communities as “racial balancing,” and indeed, warns against such policies. Instead, it allows housing developers to work with states to show that certain projects serve a valid interest, whether it be rejuvenating a depressed neighborhood or creating new housing for minorities in a wealthy area.

“The [Fair Housing Act] does not decree a particular vision of urban development; and it does not put housing authorities and private developers in a double bind of liability, subject to suit whether they choose to rejuvenate a city core or to promote new low-income housing in suburban communities,” Kennedy writes.

Many housing advocates still worry that this ruling will lead to less spending on housing in high-poverty, inner cities that need the most help.

“They're going to leave the neighborhood-based programs in the dust,” Mark Rogers, the executive director of Guadalupe Neighborhood Development Corporation, an East Austin-based housing group, told me.

Indeed, some Austin projects built before the Inclusive Communities lawsuit that have helped to revitalize high-poverty neighborhoods would not have won tax credits now, Julian Huerta, the deputy executive director of Foundation Communities, an Austin tax-credit developer, told me. M Station, a project approved in 2009 and located in East Austin, would have lost in the tax-credit process to another Foundation Communities development in Austin’s wealthy west side, called Southwest Trails.

This was also a concern expressed by the minority in the Supreme Court case. Frazier Revitalization Inc. had filed a brief arguing that recognizing disparate-impact claims could limit its goal of bolstering a high-poverty neighborhood. Giving credits to wealthy areas violates “the moral imperative to improve the substandard and inadequate affordable housing in many of our inner cities,”the brief argued.

Failing to improve substandard housing could also be argued to have a “disparate impact” on minorities, Justice Alito argues. The decision leaves it up to HUD to decide which policies adversely affect minorities, and which don’t. But that plan is too vague to work.

“The effect of these regulations, not surprisingly, is to confer enormous discretion on HUD—without actually solving the problem,” he writes.

But John Henneberger, an affordable-housing advocate in Texas, says there is a way to balance both concerns, and the court’s majority understood that. At the end of the day, this case is less about race, he said, than it is about choice.

“There needs to be a balance, and everybody acknowledges that, between revitalization and creating choices in other areas,” he said. “What it means is that a state like Texas cannot deny applications, cannot steer all of its affordable-housing stock into the poorest and most racially segregated parts of the city. It has to provide its citizens choice.”