The Equalizer: Bill de Blasio vs. Inequality

The New York City mayor has some big ideas, but they may be too much too fast.

This past may, Bill de Blasio, the first-term mayor of New York City, traveled south from his home turf to Washington, D.C. He had come to solve America’s problems. “What I’m trying to do with the progressive agenda goes far beyond the boundaries of the Democratic Party,” he told me, in the large suite of offices that New York City maintains in downtown D.C. “It’s about changing our national debate and, ultimately, changing policies.” In less than an hour, de Blasio would present what he was grandly calling “The Progressive Agenda to Combat Inequality” during a sweaty press conference on the Capitol lawn, thereby seeking his place as one of the principal combatants in the current battle for the soul of his party.

“I think the Democratic Party needs to get back to its roots,” he told me, his words rapid and full of impatient certitude. “We are a party that’s supposed to be about progressive economic policies and economic populism. And we’re supposed to speak for the needs of working people of every background, of every region. And I don’t think, as a whole, the party has done a good enough job.”

De Blasio is an ungainly 6 foot 5, with the hooded eyes and dour countenance of Sam the Eagle, the Muppets’ harrumphing, censorious patriot. He can sometimes be oblivious to the way his actions come across, and as we spoke, he rubbed moisturizer into the backs of his long, hairy hands. He periodically pulled a flip phone—which he keeps for personal use to supplement the BlackBerry holstered at his hip—out of his suit pocket to check his text messages.

In de Blasio’s view, the Democrats got slaughtered in the 2014 midterm elections not because voters rejected liberal ideas but because voters wanted more of them—and too few Democratic candidates delivered. It is time, he said, to jettison the timid centrism—tough on crime! pro-business! down with Big Government!—that Democrats have relied on since the Bill Clinton years. “What happened in the 2014 election is a lot of candidates—I would certainly say this about a lot of Democrats—did not want to say out loud the crisis that we’re facing, and I think that’s a huge mistake,” he said.

The crisis he was referring to, income inequality, has risen to become one of the central preoccupations of American politics as the 2016 presidential election comes closer. In a Pew survey last year, inequality was Americans’ top choice for “greatest threat to the world.” Even Republicans are talking about it. None other than Mitt Romney has said, “The rich have gotten richer, income inequality has gotten worse, and there are more people in poverty than ever before.”

In the Democratic presidential primary, Senator Bernie Sanders’s insistent focus on inequality, which he calls “the great moral issue of our time,” has posed an unexpectedly stiff challenge to Hillary Clinton. But Clinton’s allies in the party’s more centrist wing fear that adopting a crusading, progressive tilt would be an electoral dead end. This intraparty debate could determine the orientation of American politics for years to come, and de Blasio wants to be in the middle of the fray.

He is uniquely positioned to make his claim on the party’s future. Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts has won the left’s heart with her tirades against big banks. And Sanders, from Vermont, has become something of a folk hero—and seen his unlikely campaign catch fire—for his rumpled rabble-rousing. But as members of the Senate minority, they can do little but spout rhetoric. De Blasio has something they don’t have: power. He commands a city bureaucracy hundreds of thousands strong; he has more constituents than most senators and governors do; he presides over a city council that is both ideologically sympathetic and structurally weak. In the nearly two years since he took office, he has embarked on an aggressive program to make the city less unequal—a program whose significance he believes most New Yorkers have yet to grasp.

De Blasio wants what he’s doing in New York to serve as an example for the rest of the country. And he wants Hillary Clinton—whose successful U.S. Senate campaign he managed in 2000—to embrace that example. To formulate the agenda he was presenting at the Capitol in May, he had summoned an all-star cast of liberals, such as Toni Morrison and Van Jones, to Gracie Mansion. He has given speeches across the country, in places like Nebraska and Iowa, about what he calls “the crisis of our time.” He planned to host a forum on income inequality in Iowa in early December, and invited the top candidates from both parties to participate—but had to cancel it when none agreed to attend.* For months, he pointedly refused to endorse Clinton, saying he needed to be satisfied that she had positioned herself correctly on his pet issue. “I think it’s time, in the coming weeks and months,” he told me in May, “for her to offer a specific vision for addressing income inequality.”

The long-delayed endorsement—part sincere expression, part attention-grabbing stunt—struck many commentators as a boneheaded move that speaks to an unearned and unbecoming grandiosity. As one source well placed in Clintonland put it to me: “Give me a fucking break.” When de Blasio marched on Washington in May, 13-point plan in hand, the New York media seemed mostly to be asking, Who do you think you are? Noting that de Blasio’s approval rating stood at just 44 percent among his own constituents, Bob Hardt, the political director of NY1, a local cable network, observed in a column, “Before heading off to the fields of Iowa again, perhaps it’s time to look homeward.”

Even some allies fret that de Blasio is getting too big for his britches. “When you’re mayor, you have the latitude to do those things, but only after you tend to business at home,” David Axelrod, the Democratic strategist and former Obama adviser, who has known de Blasio for more than a decade, told me. “He has to be very careful, I think, not to play so hard at the national game that he is perceived as neglecting his responsibilities.”

De Blasio brushes off such concerns. “I think we have a broken situation in Washington, D.C.,” he told me. “That is not a news flash. We know this. We know the issue of income inequality is not being addressed. We know the middle class is in great danger. We’ve got to have a breakthrough here. And I have the honor of being mayor of the biggest city in the country. It’s my obligation to act on these issues for my own constituents.”

Whether de Blasio is able to change the course of the country will depend on a couple of questions: Is his project in New York working? And do people like it? The mayor is finding, over the course of nearly two years in office, that the answers to those questions are not as closely linked as they might seem.

In september, New York’s Transport Workers Union took out a newspaper ad featuring de Blasio’s face superimposed on a graffiti-covered subway car. “Mayor de Blasio risks taking us back to the bad old days of the 1970s and 1980s,” it said. Chris Christie, the governor of New Jersey and a Republican presidential candidate, has decried the “diminution in the quality of life” in the city, blaming it on de Blasio’s “liberal policies.” In one poll last spring, just 8 percent of New Yorkers rated the mayor’s job performance as “excellent”; one voter, Rochelle Weinberg, a Democrat from Queens, told The Wall Street Journal: “I can’t stand him. Everything he does makes me angry.”

The New York Post, the city’s conservative tabloid, has seized on anecdotal reports of disorder, from the prevalence of panhandlers to the appearance of topless performers in Times Square, to depict de Blasio’s New York as an urban hellscape. A cover last year blared, “Squeegee men back: BAD OLD DAYS,” teasing an investigative report that had turned up all of two examples of the marauding Windexers famously targeted by former Mayor Rudy Giuliani in the ’90s. Squeegee men, the article said, had returned and were “terrorizing” the city.

This tableau of decline is not what de Blasio sees when he surveys his domain. What he sees is progress. His signature achievement to date has been the introduction of free prekindergarten education for every child in the city, a feat he accomplished in his first year. He created a war room across the street from City Hall that met seven days a week to steer the breakneck implementation. And when the new pre-K classrooms opened in September 2014, even some of the mayor’s critics conceded that it was a huge accomplishment. Now in its second year, the program serves more than 65,000 city children—more pre-K students than there are students of all ages in the entire Boston school district—including half of New York’s homeless children.

Under de Blasio, the city has also mandated that employers offer paid sick leave, raised the minimum wage for certain workers, and created a new ID card that helps undocumented immigrants get access to banks and other services. The card has proved hugely popular—more than half a million have been issued. Some rents have been frozen, for the first time in half a century—providing relief to more than 1 million New Yorkers—and more than 20,000 units of affordable housing have been created or preserved. Together with Police Commissioner William Bratton, the community-policing pioneer who held the job under Giuliani in the 1990s, de Blasio has dialed back the NYPD’s stop-and-frisk policy and stopped arresting people caught with small amounts of marijuana.

De Blasio, in other words, is making the city less unequal, little by little, just as he promised to do. “The sheer amount of dollars de Blasio’s policies has shifted into the hands of working class New Yorkers is truly staggering,” the Daily News columnist Juan Gonzalez wrote in September. “No wonder the 1%—those who had it so good for so long—want him out.”

These aren’t just nice new programs, allies argue—they’re proof that liberals can be effective, contra the stereotype of mushy-headed do‑gooders whose well-intentioned efforts fall prey to dithering, bureaucracy, and overspending. “New York City, the supposedly ungovernable city, added an entire grade to the largest school system in America without a hitch,” Peter Ragone, a longtime adviser to de Blasio, told me. “That only happens through really strong management. There’s no way around that.” The economy is strong, the city’s budget is running a surplus, test scores are up, and overall crime is down. Over the summer, when many other cities saw an increase in murders, New York had the fewest in 25 years.

But this sunny picture has not exactly been the popular perception. A series of trivial flubs have chipped away at de Blasio’s public image. He was widely mocked for eating pizza with a knife and fork, and at his first Groundhog Day ceremony, he dropped the groundhog, which later died. (At his second Groundhog Day, to prevent mishaps, Staten Island Chuck was presented in a plexiglass enclosure.) Throughout his first year, he was chronically late, even by New York standards. His attempt to limit the growth of Uber—perhaps on behalf of the taxi union, a political ally—was shelved after the company targeted de Blasio with protests and attack ads. And during a violent standoff on Staten Island in August, during which a firefighter was shot, de Blasio was discovered working out, mid-morning, at a gym in Brooklyn. Even among those constituents who do not see de Blasio as a radical bent on redistributing their wealth to minorities, a view persists of his administration as an embarrassing comedy of errors, and the mayor as its fool—tall, doofy, and deluded. Who cares how much good you’re doing if New Yorkers have decided you’re a putz?

In october, de Blasio appeared on CNN with his own version of Donald Trump’s signature hat. It read make america fair again. Although de Blasio embraces the term progressive, with its suggestion of forward motion, his liberalism has a fundamentally nostalgic cast. He believes he is reaching back to an older tradition—a vanished time when broadly shared prosperity gave people good jobs and good wages. He invokes the progressive heritage of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Fiorello La Guardia, two men his Italian mother and her two sisters so admired that it often felt like they were invisibly present at family gatherings in the 1970s and ’80s.** “They talked about them all the time,” de Blasio told me. Never mind that the postwar years were far from fair for women, or blacks, or gays; de Blasio, like Trump, is tapping into a widespread sentiment that America’s best days may have passed.

Bill de Blasio was born Warren Wilhelm Jr. (as a young adult, he adopted a combination of his childhood nickname and his mother’s maiden name) in 1961 to a pair of 44-year-old liberal intellectuals. His family was haunted by McCarthyism: In 1950, both of his parents, Maria and Warren Wilhelm, had to defend themselves against charges of communist sympathies before a government-loyalty board. (Maria worked as a researcher at Time magazine, where her outspoken liberalism raised the hackles of one of the writers, the noted anti-communist Whittaker Chambers.) Though they were cleared, the investigation stymied Warren’s career as a Commerce Department economist and set off a gradual, alcohol-fueled decline. He left the family when de Blasio was in elementary school. A decade later, he shot and killed himself in the parking lot of a Connecticut motel.

De Blasio’s friends say this heritage has given him a profound leftist identity. “His mother was denounced by Whittaker Chambers. His father basically had his career ruined by McCarthyites,” one told me. “On a deep, deep level, he knows that there really is a right wing, and it’s not nice.”

Thus, while many in his generation thrilled to the vision of Ronald Reagan, de Blasio had a very different reaction. Reagan’s election, he told me, was “a shock like you would not believe,” one that he sees as the root of virtually every pernicious economic trend—“deregulation and trickle-down economics and globalization.” When I noted that a lot of people had found Reagan compelling, de Blasio shot back, “Well, I don’t know many of those people.”

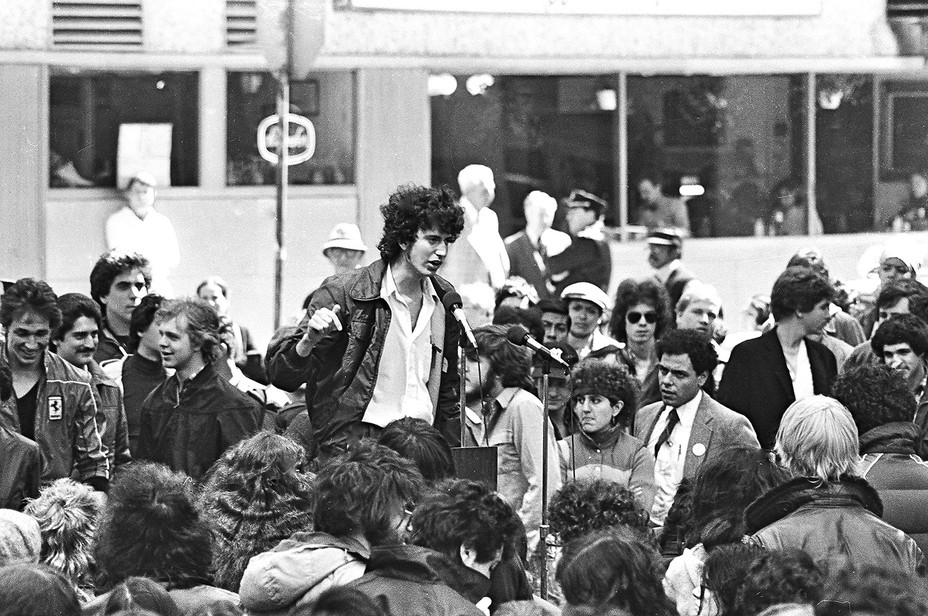

De Blasio’s young adulthood reads as a near-parody of a 1980s lefty’s life. After earning a master’s degree in international affairs from Columbia University, he went to Nicaragua to help the Sandinistas; he marched in protests against the Three Mile Island nuclear-power plant. He worked on David Dinkins’s 1989 mayoral campaign, then took a job at City Hall, where, in 1991, he met Chirlane McCray, an African American poet, activist, and speech writer. In 1979, McCray had written an essay for Essence titled “I Am a Lesbian.” De Blasio wooed her nonetheless, and in 1994, they were married in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park.

De Blasio continued to pursue a career in government, working under Andrew Cuomo in Bill Clinton’s Department of Housing and Urban Development. In 1996, he directed the New York State campaign for Clinton’s reelection. When Hillary Clinton, then still the first lady, decided to run for Senate in 2000, she tapped de Blasio to manage her campaign.

Harold Ickes, the former Clinton adviser, who has known de Blasio since his Dinkins days, told me that de Blasio initially hesitated to take the job managing the Senate campaign, because he was intimidated by the complexities of the Clintons’ world. “I said to him, ‘You can bring the good news and I’ll bring the bad news,’ ” Ickes said. “We did that a lot of times—he’d call me and say, ‘Would you mind calling Hillary and talking about X, Y, or Z issue?’” De Blasio’s management style was laid-back and indecisive, and toward the end of the campaign he was removed from the chain of command, according to The New York Times. Ickes told me that wasn’t the case. The perception, he said, was based on a misunderstanding of de Blasio’s role: His job was to guide Clinton through the ins and outs of New York politics, not to serve as an overall strategist.

It was clear to Ickes even then that de Blasio intended to seek office himself someday. “He always talked about it, but in New York, it’s like getting your ticket to the fish counter at Zabar’s on a Friday night—you have to stand in a long line,” Ickes told me. After Hillary Clinton’s election, de Blasio ran for a Brooklyn city-council seat. “And the rest is history, as they say.”

To de Blasio’s allies, the twin strands of his biography—staunch liberal who’s sure of his principles, and political operative who understands electoral sausage making—constitute just the combination needed to bring about New York’s progressive transformation. “He’s basically an idealist who makes deals to get things done,” Howard Dean, the former governor of Vermont and a friend of de Blasio’s, told me. “He’s not starry-eyed. But he’s also not a guy who’s only interested in his own power.”

One persistent criticism, however, is that de Blasio’s certitude leaves little room for alternate approaches. At one point, I asked him how he would adjust his worldview if his policies turned out to be ineffective—if, as his critics warn, crime and deficits and the squeegee men returned. He said his approaches had already been tested. “We’ve picked up on some policies that have already been successful elsewhere,” he said. When it came to questions like the value of prekindergarten, he said, “I think the jury came back a long time ago.”

Despite new york’s reputation as a liberal bastion, before de Blasio’s election the city had not had a Democratic mayor since Dinkins left office, in 1993. The odds-on candidate to replace Michael Bloomberg in 2013 was the city-council speaker, Christine Quinn, who had cozied up to business interests and helped Bloomberg win a third term by getting rid of the city’s two-term limit. (She had defeated de Blasio for the speaker position in 2005.) Bloomberg was still popular with majorities of city voters and of Democrats; Quinn positioned herself as the candidate who would stay the course in good times.

But de Blasio correctly sensed that a liberal wind was blowing. He was at the vanguard of a progressive takeover of city politics that began in 2009, when he won the primary for the citywide office of public advocate in a surprise upset. De Blasio was endorsed by the Working Families Party, a labor-backed, left-wing coalition that also helped seven liberal challengers win city-council primaries and special elections that year. Once in office, they joined with other liberals on the council to form an 11-member progressive caucus. They were a minority on the 51-seat council, but they quickly proved capable of driving the agenda—and irritating Bloomberg—by, for example, pushing for paid sick leave and against stop-and-frisk. Quinn opposed the progressives on both issues, beginning her alienation from the Democratic base.

De Blasio promised, in his campaign, to fund his pre-K proposal through a new tax on incomes above $500,000—a way to help the poor by taking from the rich. But once he assumed office, after coasting in the general election with 73 percent of the vote, the Democratic governor, Andrew Cuomo, countered by announcing that the state would fund the pre‑K expansion without raising taxes. De Blasio insisted that the tax hike was necessary to ensure future funding, and he lobbied lawmakers to pass it. At the same time, he announced that some public charter schools would no longer get free space in public-school buildings—a policy change that charter-school advocates took as a declaration of war.

Eva Moskowitz, the CEO of the Success Academy public-charter chain and a target of de Blasio’s, told me that she believes de Blasio has been blinded to alternate approaches by his ideology and by his loyalty to the teachers union. “His views of the solution don’t look that different from those being proposed 30 years ago,” Moskowitz said. “I’ve watched up close for many, many years, and those solutions do not work.”

Not long after de Blasio was sworn in, as he was trying to gin up support for his pre-K tax, charter-school advocates held a massive rally in Albany—headlined by Cuomo—and aired television ads blasting the mayor as anti-student. The blowback helped doom de Blasio’s tax proposal. So while he publicly claims victory for getting pre-K funded and running, sources close to him say he privately acknowledges that he lost the battle. “He got his clock cleaned by Cuomo in Albany the first year,” says one de Blasio ally. “He knows he misplayed it.”

De Blasio was determined to get better results from the second legislative session of his term. He stumped across the state to get more Democrats elected to the legislature in 2014. And he strenuously avoided criticizing Cuomo. That wasn’t easy, as the governor continually found large and small ways to needle the mayor, from refusing to consider de Blasio’s plan to redevelop a rail yard in Queens to announcing a restrictive Ebola quarantine in the fall of 2014 without consulting him. Last winter, Cuomo, who oversees the city’s transit system, blindsided de Blasio by announcing that the subways would close ahead of a snowstorm—de Blasio found out about the closure when it was reported by the media. A cartoon in the Daily News depicted de Blasio as a housefly and Cuomo as a sadistic teenager ripping off one of his wings.

De Blasio ignored the provocations. He even helped Cuomo at a crucial moment. Up for reelection in 2014, Cuomo faced a primary challenge from Zephyr Teachout, a law professor recruited by the Working Families Party. The party saw Cuomo as exactly the sort of Wall Street Democrat it was trying to drive out: Despite being the son of one of de Blasio’s progressive idols (the mayor’s “tale of two cities” campaign slogan was also the refrain of Mario Cuomo’s landmark Democratic National Convention speech in 1984), Andrew Cuomo built his career on a socially liberal but fiscally conservative platform, cutting taxes on the wealthy as he pushed gay marriage through the legislature. The Working Families Party’s mission is to make this kind of moderation unacceptable. “We want to do to Democrats what the Tea Party did to Republicans,” the party’s national director, Dan Cantor, told me.

Though the WFP had persuaded Teachout to run against Cuomo, de Blasio urged the party to support the incumbent, seeing an opportunity to build leverage with a governor who was almost certain to win reelection. De Blasio brokered a deal in which the governor made a series of promises to the progressives: He said he would fight to help Democrats retake the state Senate, to increase the minimum wage, and to enact campaign-finance reform. Cuomo recorded a videotaped address to the WFP’s convention, where members were hotly divided over which candidate to back. When some complained that in the video Cuomo had avoided making his promises explicit, de Blasio arranged to get Cuomo on speakerphone to make the commitments the delegates were waiting to hear.

It was a close call, but Cuomo won the group’s endorsement, which would seem to have put him in de Blasio’s debt. Yet the governor proceeded to renege on the deal. He not only didn’t lift a finger for Democratic Senate candidates, he started a new party, the Women’s Equality Party, aimed at undermining the similarly acronymed WFP and draining its ballot share. Cuomo won reelection with 54 percent of the vote, a slimmer margin than expected. De Blasio and the Working Families Party, in the words of New York magazine, “got played.”

De Blasio’s efforts to get more Democrats elected to the legislature also backfired. Almost all the candidates he’d campaigned for lost; some were attacked for their association with the liberal mayor. The Republicans elected in their stead were annoyed with de Blasio as a result of his efforts against them. When the legislature convened this year, Cuomo completed the humiliation by antagonizing de Blasio more brazenly than ever. Cuomo and the split legislature conspired to deny virtually all of de Blasio’s requests, refusing the changes to housing policy he sought and passing an insulting one-year extension of mayoral school control, rather than the permanent extension he had asked for. In newspaper articles, an anonymous “top Cuomo administration official” trashed de Blasio’s strategy, telling the Daily News, “He puts himself in these situations.” The press quickly sniffed out this official’s identity: Cuomo himself.

De Blasio had finally had enough. In an interview with NY1, the cable network, he abandoned the pretense of comity and accused Cuomo of shortchanging the city out of pure spite: “In my many efforts to find some common ground, suspiciously, it seemed that every good idea got rejected or manipulated.” Many on the left cheered at the venting of their long-held frustrations. But beyond catharsis, it wasn’t clear what de Blasio hoped to achieve with his broadside. In recent polling, Cuomo’s approval rating in New York City came in higher than de Blasio’s.

The greatest test of de Blasio’s progressive ideals has been the city’s convulsions over police brutality. Last December, after a grand jury declined to indict the white police officer who’d choked Eric Garner to death, the mayor seemed to side with the protesters and against the police. De Blasio said he worries about the danger his own son, who is biracial, faces at the hands of police. “We’ve had to literally train him, as families have all over this city for decades, in how to take special care in any encounter he has with the police officers who are there to protect him,” he said.

Two weeks later, two officers were shot and killed as they sat in their patrol car. “There is blood on many hands tonight,” the head of the police union, Pat Lynch, said of the killings. “That blood on the hands starts on the steps of City Hall, in the office of the mayor.” At the slain officers’ funerals, hundreds of police officers turned their backs on de Blasio.

Had this happened in the 1990s, when fear of crime was at its height, such a moment could well have been a breaking point—the moment when the mayor lost the city, when the silent majority’s fear of disorder turned into a visceral rejection, when New Yorkers joined the officers in turning their backs on the mayor. But in 2015, that didn’t quite happen. Instead, about 70 percent of New Yorkers told pollsters they disapproved of the union’s actions and Lynch’s comments.

The incident made clear that times have changed since Bill Clinton and the Democratic Leadership Council saved the party from itself in the ’90s—a time when the party’s image as soft on crime was its biggest obstacle to mainstream success. Public sentiment has changed in other ways, too, since Clinton urged the party to move to the middle. Americans are far more liberal than they used to be on social issues like gay marriage. This year, 24 percent of Americans said they consider themselves liberal, a record high in Gallup’s two decades of polling the question (though still well behind the 38 percent who call themselves conservative and the 34 percent who call themselves moderate).

“The Wall Street Democrats do not seem to understand that the debate has changed,” Michael Podhorzer, the political director of the AFL-CIO and one of the left’s top strategists, told me. “There is a sense of entitlement, and a failure to comprehend that the threat is more than rhetorical. But the reality is, a Wall Street Democrat can’t win today.” Podhorzer advises Democrats against campaigning explicitly on “inequality,” a word, he says, that resonates only with elites. But a platform of worker-friendly issues, such as raising the minimum wage and implementing paid family leave, can galvanize a wide spectrum of voters.

Moderate Democrats, meanwhile, tend to break out in hives when they hear de Blasio argue that they would win more elections if they just tacked to the left. They hear in his words a latter-day echo of the Jesse Jackson–style interest-group liberalism Bill Clinton rejected. “There are a lot of Democrats and Republicans who aspire to be wealthy themselves,” Jack Markell, the centrist governor of Delaware, told me. “If we say to people, ‘The rich are the problem,’ I don’t think that’s a particularly good strategy.” Elaine Kamarck, a political scientist and Democratic operative who in 1989 co-wrote a manifesto that established the stance of the centrist Democratic Leadership Council, told me bluntly that if Democratic candidates move sharply to the left, “they will lose.”

Hillary Clinton, in her current incarnation, has largely seemed to take the centrists’ side of the argument. In Ohio in September, she told a group of women, “You know, I get accused of being kind of moderate and center. I plead guilty.” But there are signs she feels compelled to heed the party’s vocal left wing. After scrupulously avoiding taking a position on the fracas over trade that split the Democrats in the spring, Clinton came out against the Trans-Pacific Partnership in October. (Warren, Sanders, and de Blasio had all strongly opposed giving Obama authority to expedite negotiations for the free-trade agreement, a major Obama priority for which Clinton had advocated as secretary of state.) She has also come out against the Keystone XL pipeline, which environmentalists loathe, and proposed a set of new regulations to rein in Wall Street.

In late October, de Blasio finally ended the suspense and endorsed Clinton, calling her “the candidate who I believe can fundamentally address income inequality effectively.”* The Clinton campaign buried the news in a press release announcing the support of 85 mayors across the country.

If de Blasio’s influence on the national discussion remains a work in progress, that hasn’t stopped him from trying to steer the global one as well. In September, he welcomed Pope Francis to New York, hailing him as “the leading moral force on this Earth” and positioning himself as an ally in the global struggle against poverty. He has made official visits to Paris and Israel. He has spoken on more than one occasion with Alexis Tsipras, the on-again, off-again prime minister of Greece, whose crusade against austerity he applauds. De Blasio told me that he recently had a “powerful conversation” with the then-mayor of Rome, who shared his frustration at being far out in front of his national government.

The New York press has consistently depicted these activities as presumptuous—a pattern that clearly irks de Blasio. Why shouldn’t the mayor of America’s largest and most cosmopolitan city be not only a national leader but an international one, too? “My job is to produce for my people in this city, the 8.4 million people that I represent,” de Blasio told me. “But I am also cognizant of the fact that we do have an impact on the national discussion. Even a little bit on the international discussion.”

Nonetheless, there are signs that de Blasio is starting to pay more attention to his image at home. On a rainy Friday in October, he was scheduled to visit Washington once again, this time to give the keynote address to a liberal group called American Family Voices. But Hurricane Joaquin was headed for the East Coast, and at the last minute de Blasio canceled his appearance. Frequently called out in the New York media for his forays onto the national stage, the mayor seemed eager to avoid the spectacle of being caught speechifying out of town while his constituents struggled to cope with a storm.

Once criticized for his refusal to engage with trivial political controversies, de Blasio lately stands accused, in a New York Times article, of having become too reactive. When Staten Islanders complained that he hadn’t spent much time in the borough, for example, de Blasio quickly scheduled a trip there. After long insisting that the city didn’t need any more police, he agreed to add 1,300 new officers. He’s even started showing up for events on time. As de Blasio continues to learn, having a strong sense of direction is only one part of being a transcendent leader. The other is convincing people to follow you.

* This article has been updated from the print version of the December issue to reflect that Bill de Blasio endorsed Hillary Clinton and canceled a planned forum on income inequality after the issue went to press.

** This article originally referred to the Democratic heritage of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Fiorello La Guardia. La Guardia was not a Democrat. We regret the error.