The Deconstruction of the K-12 Teacher

When kids can get their lessons from the Internet, what's left for classroom instructors to do?

Whenever a college student asks me, a veteran high-school English educator, about the prospects of becoming a public-school teacher, I never think it’s enough to say that the role is shifting from "content expert" to "curriculum facilitator." Instead, I describe what I think the public-school classroom will look like in 20 years, with a large, fantastic computer screen at the front, streaming one of the nation’s most engaging, informative lessons available on a particular topic. The "virtual class" will be introduced, guided, and curated by one of the country’s best teachers (a.k.a. a "super-teacher"), and it will include professionally produced footage of current events, relevant excerpts from powerful TedTalks, interactive games students can play against other students nationwide, and a formal assessment that the computer will immediately score and record.

I tell this college student that in each classroom, there will be a local teacher-facilitator (called a "tech") to make sure that the equipment works and the students behave. Since the "tech" won’t require the extensive education and training of today’s teachers, the teacher’s union will fall apart, and that "tech" will earn about $15 an hour to facilitate a class of what could include over 50 students. This new progressive system will be justified and supported by the American public for several reasons: Each lesson will be among the most interesting and efficient lessons in the world; millions of dollars will be saved in reduced teacher salaries; the "techs" can specialize in classroom management; performance data will be standardized and immediately produced (and therefore "individualized"); and the country will finally achieve equity in its public school system.

"So if you want to be a teacher," I tell the college student, "you better be a super-teacher."

I used to think I was kidding, or at least exaggerating. Now I’m not so sure. When I consulted a local career counselor who is on the brink of retirement after a lifetime in the public schools, he said I was wrong about my prediction—but only about it taking 20 years. "Try five or 10," he said.

I smiled and laughed, and then suddenly stopped. I thought about how many times I had heard the phrase "teacher as facilitator" over the past year. I recalled a veteran teacher who recently said with anguish, "we used to be appreciated as experts in our field." I thought about the last time I walked into a local bookstore, when the employee asked if she could order a book for me from Amazon. Are teachers going the way of local bookstores? Suddenly I felt like the frog in the pot of water, feeling a little warm, wondering if I was going to have to jump before I retire in 20 years. Try five or 10.

I started reflecting. A decade and a half ago, I dedicated two years toward earning a master’s degree in English literature; this training included a couple of pedagogy courses, and it focused on classic literature, the nature of reading and writing, and the best ways to teach it. A decade ago, my school sent me to an Advanced Placement English conference at which I studied literary analysis for three days. As with the graduate program, I don’t remember the conference involving technology—it was simply the teacher, students, and a lot of books. Now, I don’t remember the last time I’ve attended, or even heard of, any professional-development training focused on my specific subject matter. Instead, these experiences concentrate on incorporating technology in the classroom, utilizing assessment data, or new ways of becoming a school facilitator.

When I did some research to see if it was just me sensing this transformation taking place, I was overwhelmed by the number of articles all confirming what I had suspected: The relatively recent emergence of the Internet, and the ever-increasing ease of access to web, has unmistakably usurped the teacher from the former role as dictator of subject content. These days, teachers are expected to concentrate on the "facilitation" of factual knowledge that is suddenly widely accessible.

In 2012, for example, MindShift’s Aran Levasseur wrote that "all computing devices—from laptops to tablets to smartphones—are dismantling knowledge silos and are therefore transforming the role of a teacher into something that is more of a facilitator and coach." Joshua Starr, a nationally prominent superintendent, recently told NPR, "I ask teachers all the time, if you can Google it, why teach it?" And it’s already become a cliche that the teacher should transfer from being a "sage on the stage" to being "a guide on the side."

I started looking around me. Teachers like me are uploading onto the web tens of thousands of lesson plans and videos that are then being consolidated and curated by various organizations. In other words, the intellectual property that once belonged to teachers is now openly available on the Internet.

And the teachers unions don’t seem to be stopping this crowdsourcing; in fact, the American Federation of Teachers created sharemylesson.com ("By teachers, for teachers"), which says it offers more than 300,000 free resources for educators. And even though its partner, TES Connect, often charges money for its materials, the private company claims that nearly 5 million resources are downloaded from its sites weekly. Meanwhile, TeachersPayTeachers.com, an open marketplace for lesson plans and resources that launched in 2006, says it has more than 3 million users, including 1 million who signed up in the past year. Close to 1 million educators have purchased lesson plans from the site, while several other teachers are earning six figures for creating the site’s top-selling materials.

I think it used to be taboo for teachers to borrow or buy plans written by other professionals, but it seems that times are changing. Just last week, I spoke with a history teacher from Santa Maria, California, who bluntly said, "I don’t ever write my own lesson plans anymore. I just give credit to the person who did." He explained, rather reasonably, that the materials are usually inexpensive or free; are extremely well made; and often include worksheets, videos, assessments, and links to other resources. Just as his administrators request, he can focus on being a facilitator, specializing in individualized instruction.

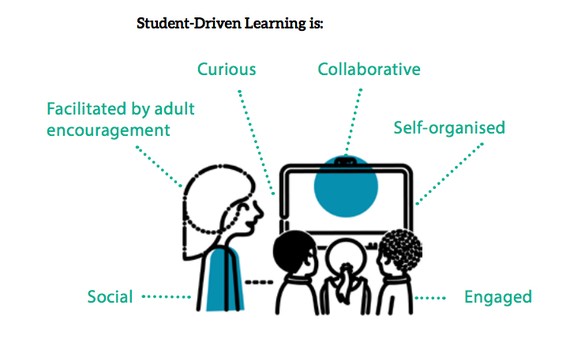

I’ve started recognizing a common thread to the latest trends in teaching. Flipped learning, blending learning, student-centered learning, project-based learning, and even self-organized learning—they all marginalize the teacher’s expertise. Or, to put it more euphemistically, they all transform the teacher into a more facilitative role.

In "flipped learning," the student is expected to absorb the core knowledge at home by watching videos and then engage in projects, problem-solving, and critical-thinking activities at school, as facilitated by his or her teacher. Project Tomorrow’s nationwide 2013 survey found that 41 percent of administrators say "pre-service teachers should learn how to set up a flipped class model before getting a teaching credential," while 66 percent of principals say "pre-service teachers should learn to create and use video and other digital media." And once again, when the teacher relies on digital media to provide the core knowledge, his or her role will inherently shift to that of a facilitator. The University of Washington’s Center for Teaching and Learning, for example, explicitly describes "flipped learning" as a way for students to "gain control of the learning process" while "the instructors become facilitators … the instructor is there to coach and guide them."

Likewise, "blended learning"—in which students take at least part of a class online while supervised by adults—is now offered by about 70 percent of K-12 public-school districts. According the Clayton Christensen Institute—a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank that touts "disruptive innovation"—the number of K-12 students who took an online course increased from roughly 45,000 in 2000, to more than 3 million in 2009. The institute also projects that half of all high-school classes will be delivered online by 2019.

I asked a longtime friend of mine—a high-school principal in northern California—to tell me candidly what he thought about blended learning. He said, "we’re at the point where the Internet pretty much supplies everything we need. We don’t really need teachers in the same way anymore. I mean, sure, my daughter gets some help from her teachers, but basically everything she learns—from math to band—she can get from her computer better than her teachers."

At a seminar about project-based learning, I told the presenter with an increasing sense of desperation, "You know, some of us English teachers still believe that teaching literature is still our primary job." He smirked and put his pointer finger near his thumb and said, "A very little part of your job." And I recently watched the TedTalk that won the $1 million prize at Ted2013, the one in which Sugata Mitra stated that "schools as we know them are obsolete" because the country no longer needs teachers. Here's how he envisions the classroom:

In the original idea of the "flipped classroom," it seems that the teacher was responsible for recording the lecture and posting the video online, but it’s now becoming more efficient to link to a professional video. And there are now thousands of videos from which to choose. The Kahn Academy—a nonprofit that claims to provide "a free, world-class education for anyone, anywhere"—features more than 6,500 free videos and advertises over 100,000 interactive lessons on various subjects. According to Forbes, more than 500,000 teachers worldwide use these videos, which also have over 500 million views on YouTube. Meanwhile, YouTube’s own education channel ("Where anyone, anywhere can learn or teach anything") has 1 million-plus subscribers. And about 2,000 TED talks are available to view for free online and have been seen more than 1 billion times total. The list goes on.

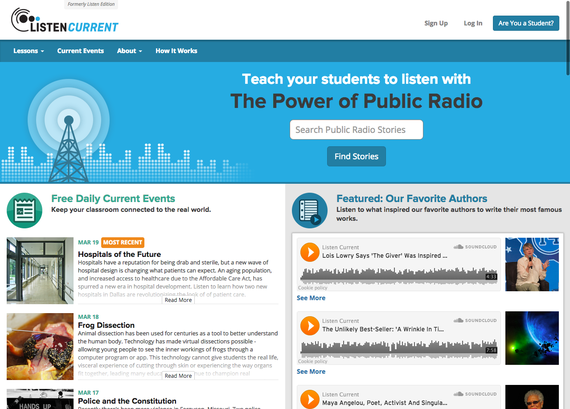

I recently spoke with Monica Brady-Myerov, the CEO and founder of Listen Current, a website that curates the best of public radio, including current events, and offers the three- to five-minute clips alongside a full set of lesson plans and worksheets. When I asked her about the recent boom in lesson-plan production, she said, "It’s like the wild west right now, both in terms of online resources and educational technology. It’s why I quit my job [as a veteran award-winning public radio journalist], so I could ride out west." Here's what Listen Current looks like:

I found brief solace in the idea that I could still be the professional teacher that compiles all these resources—and then I found Edmodo. Branding itself as the "Facebook for schools," Edmodo started in just 2008 and now has more than 48 million members. I signed up just to see what it was all about. Within five minutes, I found a great lesson on Romeo and Juliet by John Green (a favorite author among teens, and on the list of Time’s "100 most influential people"), a Kahn Academy video, immediate access to 100 famous speeches, and a somewhat fun interactive game based on Lord of the Flies. According to EdSurge, the Edmodo CEO earlier this month said, "We want to do for teacher resources what Netflix does for movies."

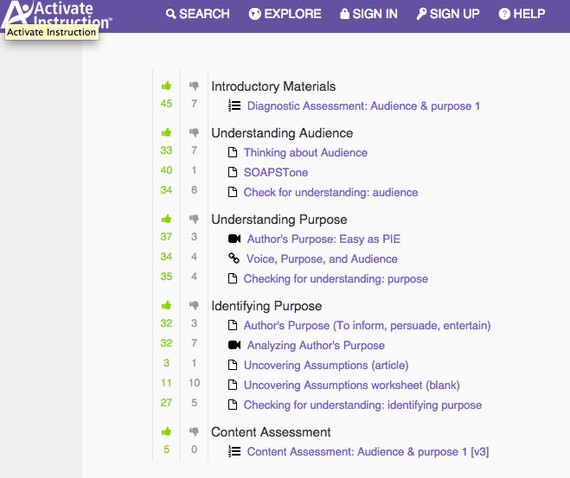

Well then. At least I can organize the video lessons and put them together in a sensible order—except that Activate Instruction is already creating a free and open online tool that is "similar to Wikipedia" and will "help put resources and curriculum in one place that any teacher can use." The company even put these materials in logical "playlists"; the first one I looked at contained 11 different professional resources for teaching a specific skill, including printable worksheets, an engaging video, an essay prompt, and a final assessment. And again, this company is just getting started—Activate Instruction was announced in 2013:

I measured myself against these websites and Internet companies. It seems clear that they already have a distinct advantage over me as an individual teacher. They have more resources, more money, an entire staff of professionals, and they get to concentrate on producing their specialized content, while the teacher is—almost by default—inherently encouraged to transform into a facilitator. Some people might cringe at a "Netflix for teachers," but it’s almost impossible to deny the inherent advantages Netflix has over a local DVD store, and it’s easy to imagine the potential improvements that could happen to these modern services.

For how many more years can I compete? A dozen years ago, I proudly worked for about 20 hours to create a lesson plan that taught poetic meter through the analysis of a rap song (I remember continually rewinding the cassette in my walkman). Last week, the first lesson I saw on sharemylesson.com was a thoroughly analyzed song by Katy Perry, with a printable worksheet that featured at least 10 literary devices, along with a link to her video. ListenCurrent.com gives me immediate access to public-radio clips that took me hours to accumulate just a few months ago. I may not use Edmodo or anything like it this year, but I also didn’t use Facebook in its first few years—or Amazon, or cell phones, or even ATM machines. Isn’t it probable that this educational technology is going to be overwhelmingly awesome in 20 years? I hear the career counselor’s voice: "Try five or 10."

I think to myself: These resources are already good for education, and they’re only getting better. Part of me is really excited that in two decades, the giant interactive classroom computer screen that I foresaw is going to be far more sophisticated than I can possibly imagine. Why should I stand in the way of crowdsourced lesson plans and professionally edited video tutorials? Shouldn’t I stop trying to compete as an individual "sage on the stage," appreciate the modern efficiency of today’s resources, and re-invest my time as their enthusiastic "guide on the side"?

When I told the school’s golf coach about flipped learning, I explained that it would be as if he asked the kids to go home and watch YouTube videos that teach proper mechanics and then practice those skills under his supervision on the course. He laughed and answered, "Oh, we should absolutely do that. Hank Haney’s video’s are way better than anything I can show them."

And if I can compete with Hank Haney, shouldn’t I be Hank Haney? In other words, if I think my lesson plans or video tutorials rival some of the best on the Internet (for now), shouldn’t I be trying to make six figures on the open marketplace at teacherspayteachers.com or as a curriculum designer for a private company? The dilemma intensifies when I suspect that un-credentialed "techs" might bust the teacher unions in 20 years ("try five or 10").

I looked through the current trends for some sign that the future classroom I envisioned won’t be realized within 20 years. I read Terrance Ross’s analysis of the Bridge International Academies and how their "scripted instruction," combined with technology and statistical feedback, has efficiently earned revenue while improving education in Kenya. Fast Company put the company on the list of "The World’s Top 10 Innovative Companies in Education," citing the fact that it’s already serving over 110,000 students, is significantly outperforming neighboring schools in both reading and math, and plans on educating 10 million students by 2025.

In a similar vein, live-streaming and other technology are also allowing some modern churches to move toward a "multisite" format, one in which a single pastor can broadcast his sermons to satellite churches guided by pastors who—this might sound familiar—concentrate on the facilitation of a common itinerary. Ed Stetzer recently wrote on ChristianityToday.com that "multisite is the new normal," and later explained, "it's easier to create another extension site than it is to create another faithful pastor who is a great communicator … it's easier to start a campus and beam my sermons to other locales than it is to raise up leaders and laypeople."

And as I mentioned earlier, last night I watched Sugata Mitra earn a standing ovation, $1 million, and a partnership with Microsoft for his TedTalk that declared that the "future of learning" is a "school built in the cloud"—one that doesn’t require teachers. It seems fitting that I watched the speech from my laptop, and that Mitra is a former computer-science teacher. Last November, Newcastle University opened the first "global hub" based on Mitra’s research, which suggests that children in self-organized learning environments "can learn almost anything by themselves" (and a computer).

This morning I spoke with a well-respected high-school teacher who supervises a blended course in digital photography. The course is mostly taught online, but students meet once every two weeks in the classroom. "So in five years, if a student has five teachers using this blended-learning style, they can just stay home the entire semester?" I asked. Apparently they could. And that, it seems, is homeschooling—with the high school’s resources.

I wonder why larger discussions related to these trends aren’t happening with greater urgency, if they’re happening at all. How hot does the water have to get before the best teachers start jumping for jobs in the private sector? As local communities and school districts nationwide commit to blended-learning programs, are they considering the long-term ramifications to the nature of their classrooms? Does the American Federation of Teachers know that, as its teachers upload their lesson plans into the cloud, they might be helping build an entirely different school, ones with self-organized learning environments instead of teachers?

I don’t have many answers in this brave new world, but I feel like I can draw one firm line. There is a profound difference between a local expert teacher using the Internet and all its resources to supplement and improve his or her lessons, and a teacher facilitating the educational plans of massive organizations. Why isn’t this line being publicly and sharply delineated, or even generally discussed? This line should be rigorously guarded by those who want to keep education professionals in the center of each classroom. Those calling for teachers to "transform their roles," regardless of motive or intentionality, are quietly erasing this line—effectively deconstructing the role of the teacher as it’s always been known.

Meanwhile, back on my campus, I wonder about the advice I should give a new teacher. Should I encourage this aspiring educator to fight for his or her role as the local expert, or simply get good at facilitating the best lessons available? Should I assure this person about my union and the notion of tenure, or should I urgently encourage him or her to create a back-up plan?

And when I think back to the original discussion, I wonder what I’m supposed to tell the college graduates who ask about earning a teaching credential. Because while I used to think I was scaring the youngster with my 20-year predictions, now I’m afraid I’m giving them false hope.