An American History of Lead Poisoning

Flint is the latest outbreak in the country’s longest-running child-health epidemic.

Roughly 9,000 children under the age of six were exposed to high levels of lead in their drinking water in Flint, Michigan, between April 2014 and October 2015. Thanks to a series of government failures, some of their lives will be forever changed by diminished IQ, damaged hearing, learning disabilities, and possibly increased criminality—the hallmarks of lead poisoning.

Sadly, those kids are not alone. Over the past century, tens of millions of children have been poisoned by lead, mainly by its presence in old household paint. And many more will be, thanks to the hundreds of tons of lead paint that remains on the walls of houses, apartment buildings, and workplaces across the United States, decades after a federal ban. Many of the most vulnerable are children living in poor neighborhoods of color.

Flint’s tragedy is shedding light on a health issue that’s been lurking in U.S. households for what seems like forever. But that demands the question: Why has lead poisoning never really been treated like what it is—the longest-lasting childhood-health epidemic in U.S. history?

According to a new paper in the Journal of Urban History by David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz, the public-health historians and co-authors of Lead Wars: The Politics of Science and the Fate of America's Children, the answer lies at the intersection of politics, class, and race.

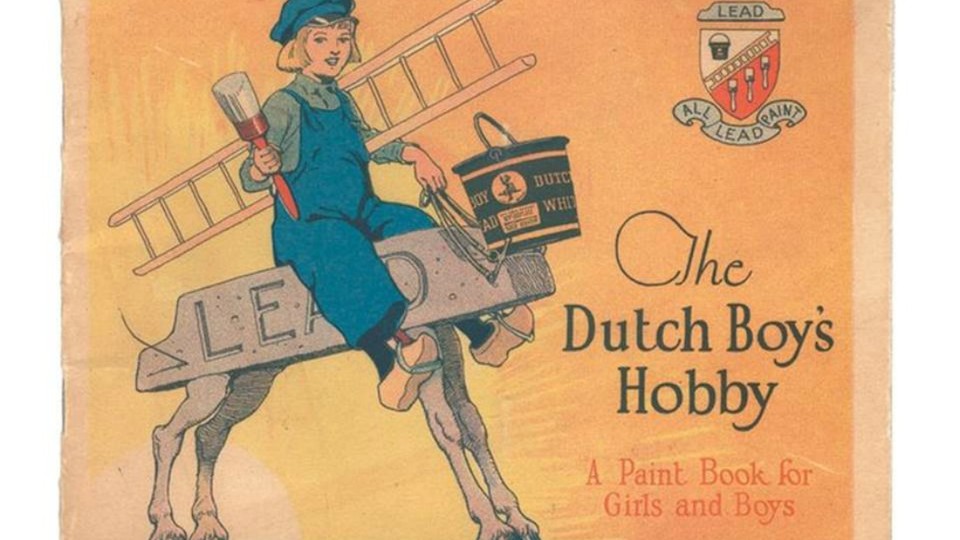

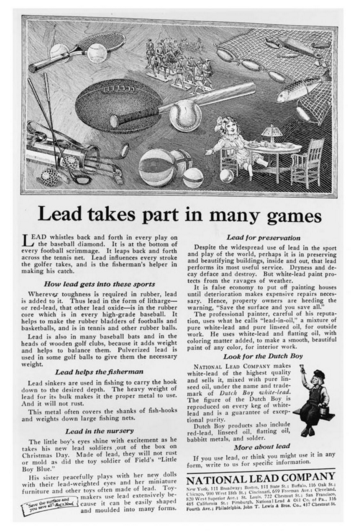

By the 1920s, lead was an essential part of the middle-class American home. It was in telephones, ice boxes, vacuums, irons, and washing machines; dolls, painted toys, bean bags, baseballs, and fishing lures. Perhaps most perniciously, it was in gasoline, pipes, and paint, the building blocks of urbanization and a growing housing stock.

That was precisely how the lead industry wanted their product to be seen. Despite the fact that lead was known to be toxic as early as the late 19th century, manufacturers and trade groups fiercely marketed it as essential to America’s economic growth and consumer ideals, especially when it came to their walls. Latching onto the nation’s post-Depression affection for clean, bright colors, they were successful.

(Deceit and Denial: The Deadly Politics of Industrial Pollution / CityLab)

But pressures on the industry began to mount by the 1950s, by which time millions of children had been chronically or acutely exposed. Federal public-health officials had documented lead’s irreversible effects for young people who ingested even trace amounts. Newspapers and public-health departments began regularly reporting new cases linked to water and wall paint.

If the lead industry had stepped up then (or if it had been forced to by government), maybe lead poisoning would have been treated like any other major childhood disease—polio, for example. In the 1950s, “[F]ewer than sixty thousand new cases of polio per year created a near-panic among American parents and a national mobilization that led to vaccination campaigns that virtually wiped out the disease within a decade,” write Rosner and Markowitz. With lead poisoning, the industry and federal government could have mobilized together to systemically detoxify the nation’s lead-infested housing stock, and end the epidemic right there.

Instead, the industry’s powerful leaders diverted the attention of health officials away from their products, and toward class and race.

“The major source of trouble is the flaking of lead paint in the ancient slum dwellings of our older cities,” Manfred Bowditch, the director of Health and Safety for the Lead Industries Association, argued at the organization’s 1957 annual meeting. “The problem of lead poisoning in children will be with us for as long as there are slums.”

The fault, then, lay not with the industry that had knowingly included poison in its product (a product that had been used to paint new homes just a few years earlier), but with “ignorant” parents living in “slums.” It was necessary “to educate the parents” about the risk of lead paint, Bowditch complained to a colleague in 1956. “But most of the cases are in Negro and Puerto Rican families, and how does one tackle that job?”

This idea, combined with the lead industry’s powerful lobbying and marketing forces, set the stage for the lead debate for decades to come. With the industry unwilling to accept responsibility for a toxic product, and with the “problem” of lead reduced to a certain type of neighborhood, Rosner and Markowitz argue that public-health officials failed to address the lead epidemic beyond reducing known damage. Caseworkers could enter children’s homes and remove lead from the walls after a child had been identified as lead poisoned. But the money and will to do major preventive public-health work—systematically removing lead from wherever children lived, before children got sick—never came.

This was true even in the 1960s, the era of “Great Society” programs such as Medicaid, urban renewal projects, and food stamps. Community activists like the Young Lords in New York and the Citizen’s Committee to End Lead Poisoning in Chicago took up lead poisoning as a symbol of urban poverty, campaigning for more blood testing for children and stronger enforcement of existing housing codes.

Although they did succeed in some respects, Rosner says that these activists still didn’t find support for much beyond reactive, rather than preventive, public-health measures. Lead was still seen as a problem that “belonged” to poor people of color. “Ironically, those activists were actually very successful in making sure that that was how the rest of the country saw it,” he says. And that kept political will to a minimum.

Rosner and Markowitz write: “A generation later, one eminent researcher would summarize the prevailing view in the 1950s and early 1960s: Lead poisoning was ‘considered a disease inevitable to slum dwelling, one for which little could be done.’”

The 1960s weren’t the end of the lead debate. New discoveries in the 1970s and 1980s revealed that the scope of America’s lead problem went well beyond low-income households—even in homes where the most obvious lead sources, like chipped paint and window sashes, had been removed. Lead in gasoline, as well as in houses, was a national problem. “Affluent Kids Also Harmed by Toxic Lead,” read a Wall Street Journal headline from 1981.

his station in Everett, Massachusetts in 1955. (AP / CityLab)

In victories over the lead industry, officials raised their standards on what constituted dangerous blood lead levels, and the federal government succeeded in phasing out lead as an additive in gasoline in the 1980s. But while affluent families could afford to detoxify their homes of lead, low-income families and those living in public housing still weren’t necessarily able to.

As federal agencies added up the enormous cost of proactive lead abatement in the millions of housing units estimated to contain the toxin, the Reagan era’s rejection of major federal programs made it seem impossible to justify. Health officials kept on treating children after they were poisoned, rather than preventing tragedy. And, says Rosner, the lead “problem” went back to something that was linked to the vulnerable and uneducated, so overwhelming in scope as to eliminate hope for eradication.

But lead poisoning in children can be eradicated. No doubt, the scale of the problem in American households is massive. Today the cost of detoxifying the entire nation of lead hovers around $1 trillion, says Rosner. Any federal effort to systematically identify and remove lead from infested households would be complex, decades-long, and require ongoing policy reform.

“But it’s also saving a next generation of children,” Rosner says. “You’re actually going to stop these kids from being poisoned. And isn’t that worth something?”

And Rosner is a tiny bit hopeful. Amid national conversations about economic inequality, a housing crisis, and the value of black and Latino lives, the attention that Flint has brought to lead might usher in the country’s first comprehensive lead-poisoning prevention program.

“It’s only expensive if you think it’s not worth doing,” Rosner says, “which is a value judgement about communities and people. And that’s where things turn tragic.”

This post appears courtesy of CityLab.