How to Get Fewer People to Commute in Cars

As the example of Seattle shows, it helps when employers try to persuade workers not to drive.

Seattle is among the fastest-growing cities in the U.S., thanks largely to Amazon’s addition of 35,000 employees since 2010. For all the economic benefits that come with growth, it has also created a variety of civic headaches, traffic chief among them.

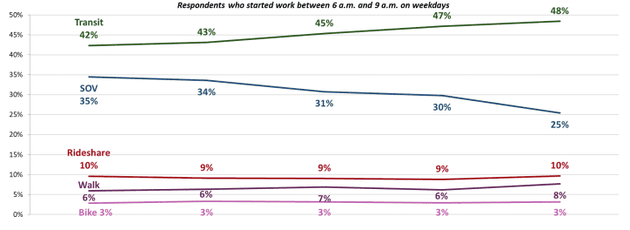

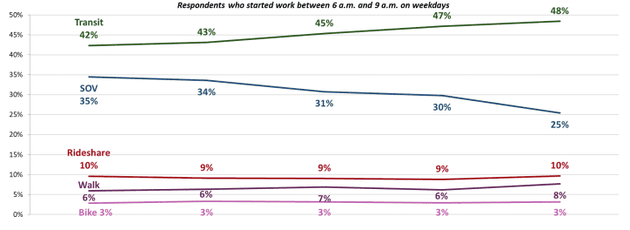

But thanks in part to efforts by the region’s largest employers, the share of commuters driving solo into downtown Seattle is on a dramatic decline. Just 25 percent of workers traveling into the city’s center drove themselves, according to the results of the latest annual commuter survey by the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) and its nonprofit partner, Commute Seattle. This is the lowest share since the city started keeping track in 2010.

The number of cars is also trending downwards, according to responses collected from 1,784 downtown workers. While Seattle has gained about 60,000 jobs since 2010, there are approximately 4,500 fewer single-occupancy vehicles.

Overwhelmingly, new workers are choosing transit. The share of commuters headed downtown by bus or train shot up from 42 to 48 percent from 2010 to 2017, with about 127,000 such trips during the average morning rush hour.* Bus trips (as anyone who’s waited at a packed King County Metro stop on a weekday morning can attest) make up the vast majority of them.

Walking, biking, and carpooling also picked up by thousands of trips per day, according to the survey. Note, though, that ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft weren’t explicitly identified as options in the survey, which comes from a state document that hasn’t changed much since 1991. Respondents might have registered those trips as “drive alone,” “other,” or as “rideshare” (meaning carpool), but there is currently no way of telling. That could be a potentially significant caveat, considering that other transportation surveys in U.S. cities, including Seattle, find ride-hailing services to have a cannibalizing effect on transit. But Jonathan Hopkins, the executive director of Commute Seattle, said the scale of their impact seems to be pretty small in downtown Seattle specifically.

Seattle has been trying to cut back on car commuting in several ways. “We have to for the city to grow,” Hopkins said. As CityLab’s Andrew Small recently reported, the region has consistently invested in expanding transit service, with new light-rail stations, a revamped bus network, and a voter-approved transportation-benefit district sprinkling transit stops within a 10-minute walk to more city residents. Sound Transit 3, the $54 billion ballot measure that passed in 2016, promises to spread more light-rail much further.

In some ways, Seattle transit is a victim of its own success—bus-stop waits can drag on as packed bus after packed bus sails by; one rider recently likened boarding the C line to “being in Lord of the Flies.” But few other cities are confronting their transit problems with significant tax dollars as Seattle is.

Next are employers. SDOT and Commute Seattle work with 270 large companies around the region, including Microsoft, Expedia, and Amazon, to promote commuter-incentive programs and strategic relocations. And not out of the goodness of their corporate hearts: In Washington State, big employers have been mandated by law since 1991 to reduce solo commutes.

The Gates Foundation, for example, has gone from a “drive-alone” rate of 88 percent to 34 percent by distributing a suite of transit benefits to employees, including free Monorail punch cards and free monthly Zipcar hours. It also disincentivizes parking: The company lot charges a daily rate instead of a monthly rate. Weyerhauser, a real-estate investment trust and timber company, decreased its employee drive-alone rates from 82 percent to 9 percent largely by relocating from the suburbs to downtown, according to Hopkins. The construction of new downtown housing options has helped, too.

Amazon has also made strides to reduce its traffic footprint, chiefly through its downtown location. It offers subsidized transit passes, and like Microsoft, it runs a private shuttle option to ferry workers from their suburban homes to its downtown campus. Both companies (alongside Expedia, Costco, and Vulcan) also donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Sound Transit 3 campaign. And, arguably, Amazon’s impending expansion into a second home city may be the greatest traffic gift the company could deliver.

This post appears courtesy of CityLab.

* This article originally stated that commuters took 41,500 trips during the average morning rush hour. We regret the error.