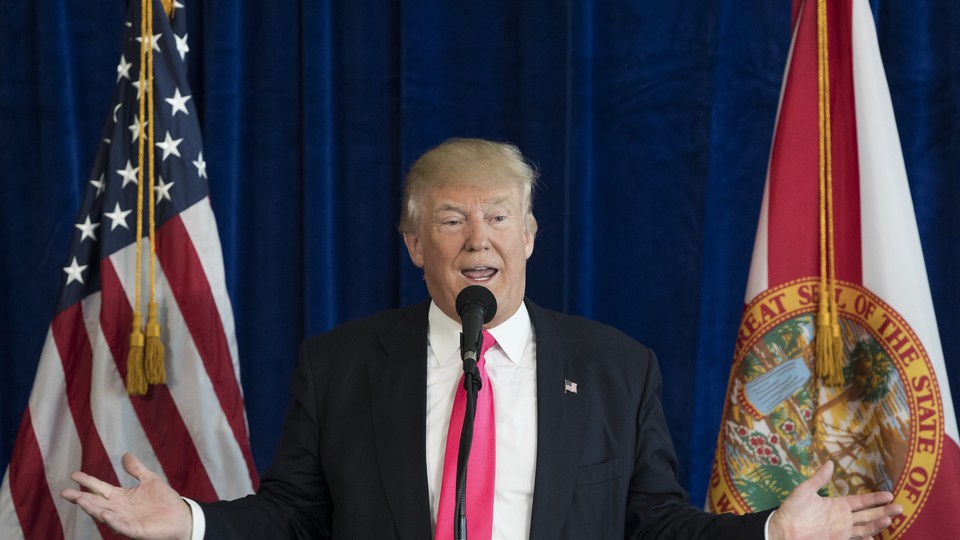

Donald Trump's Crimean Gambit

The Republican presidential nominee appeared to suggest he’d recognize Russia’s annexation of the Ukrainian territory in 2014.

Donald Trump’s call on Russia to hack Hillary Clinton’s emails Wednesday resulted in widespread criticism. But his comments on Crimea, coupled with ones he made last week on NATO, are likely to have greater significance if he is elected president in November.

The question came from Mareike Aden, a German reporter, who asked him whether a President Trump would recognize Crimea as Russian and lift sanctions on Moscow imposed after its 2014 annexation of the Ukrainian territory. The candidate’s reply: “Yes. We would be looking at that.”

That response is likely to spread much cheer through Russia—already buoyant about the prospect of a Trump victory in November. But it could spread at least an equal amount of dread in the former Soviet republics. In a matter of two weeks, the man who could become the next American president has not only questioned the utility of NATO, thereby repudiating the post-World War II security consensus, he also has seemingly removed whatever fig leaf of protection from Russia the U.S. offered the post-Soviet republics and Moscow’s former allies in the Eastern bloc.

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev gave Crimea, a region that had been part of Russia for centuries, to Ukraine in 1954—though, to be fair, Khrushchev probably didn’t foresee that the Soviet Union would be the stuff of history books less than four decades later. Russia maintained close links to Crimea even after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It helped that of all the Soviet republics, save Belarus, Ukraine maintained the most pro-Moscow positions until 2014. More than half of Crimea’s 2 million people were Russian; Russia maintained a naval base in the region; and Russians retired in Crimea in large numbers. But when Ukraine’s pro-Moscow president, Viktor Yanukovych, was ousted, the tensions over Crimea became apparent.

In 2014, pro-Russian gunmen took over government buildings in Simferopol, Crimea’s capital, and held a referendum in May of that year in which an overwhelming majority of voters said they wanted to rejoin Russia. The West reacted with anger and imposed a string of sanctions on Russia—sanctions that even Putin acknowledged adversely affected Russia’s economy, which was already hurt by falling oil prices. Last year, on the anniversary of Russia’s annexation, the U.S. State Department said: “We do not, nor will we, recognize Russia’s attempted annexation and call on President Putin to end his country’s occupation of Crimea.”

Trump, as president, may reverse that policy, and if he does Ukraine won’t be the only country that worries. Another is likely to be Georgia, the former Soviet republic. A brief war with Russia—brief in that Georgia was crushed—in 2008 resulted in Russia extending support to two breakaway Georgian regions, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and wielding its influence with the rebels there. Russia’s recent military exercises, as well as its statements, have also worried Eastern European states such as Poland and the Baltic nations that share a border with it.

Until recently, many of them could have counted on NATO’s support, but Trump last week made military support conditional on whether those countries had paid their financial dues to the alliance—a marked departure from the security policy of every presidential nominee from either of the two major parties since NATO’s founding in 1949. As I pointed out at the time, “If Trump is elected in November and is true to his pledge, then few of NATO’s 28 members will qualify for U.S. support in the event of a war. Only the U.S., Greece, the U.K., Estonia, and Poland meet NATO’s guideline that defense spending constitute 2 percent of GDP.”

Now, with his comments on Crimea, Trump has given the foreign-policy establishment in the U.S. and Europe even more to consider before November.