Erie's Unlikely Benefactor: Its Casino

Legalized gambling is a familiar part of the modern American landscape. But an innovative scheme in a lakeside city in western Pennsylvania shows new possibilities for putting casino revenue to positive public use.

From the beginning, liberal democracies have faced this challenge: how to provide long-term resources for public benefit, in political systems that are always oriented toward the next election and by “what’s in it for me?”

FDR came up with his own solution during the Depression, with his belated discovery of the power of large-scale infrastructure spending. In almost every one of the dozens of cities Deb and I have visited, we’ve found libraries, post offices, overpasses, parks with little plaques showing a construction date in the mid-1930s and the message, “Built by the WPA.” (You can find a fabulous archive of remaining WPA projects at UC Berkeley’s “Living New Deal” site.)

The post-World War II California of my youth, under Governor Pat Brown, could draw on the always-growing revenues from its always-expanding economy to fund its new universities, parks, and freeways. Then as its economy slowed in the mid-1970s the state tragically hamstrung itself by passing Proposition 13, moving its public schools from among-the-best-funded to among-the-worst-funded in the country. On the national scale, I frequently think of the book A Country Made by War, by Geoffrey Perret, which argues that the United States has often leaned on the excuse of “national defense” to do what would be considered “industrial policy” or “long-term economic development” anyplace else. America’s aerospace dominance was fostered by the military; its Interstate Highways were built under the same rationale; so too with early semiconductor and internet research.

As we’ve visited cities around the country, we’ve noted a wide range of variations for better and worse in responses to the challenge of investing for the public good. San Bernardino, California, has much more than its share of “normal” economic woes, which have been worsened by a bizarre city charter that makes it very hard for the city to pay its way. (That charter is at long last now under reconsideration.) Pittsburgh has gone through its long heavy-industrial decline and tech-driven renewal, but it would have been in far worse shape without the concentration of industrial-area philanthropies—Heinz, Mellon, Frick—still involved there. Detroit has outsized challenges but is also the focus of unusual national attention from governmental, charitable, and civic-action groups. Dodge City, Kansas, as we’ve outlined before and will explain in more detail soon, found an inventive way, through its “Why Not Dodge?” campaign, to create a permanent war-chest for civic investments and improvements. Allentown, Pennsylvania, engineered a state tax-refund program that has been a (mainly) effective for redevelopment of its downtown.

And now comes Erie, where a big surprise on our recent visit was the role of something called ECGRA.

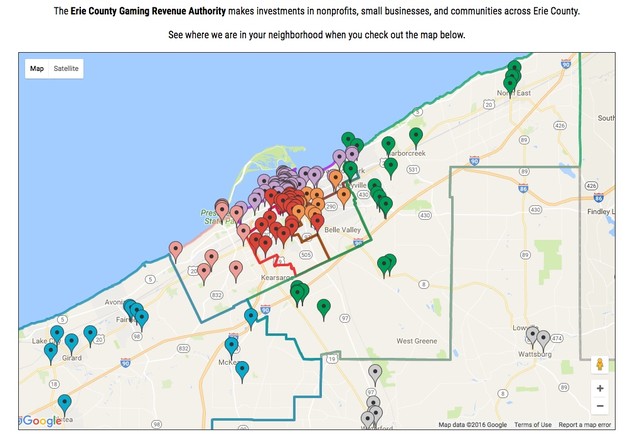

The acronym ECGRA, usually spoken as “eggrah” rather than spelled out, stands for Erie County Gaming Revenue Authority; its site is here. It exists because in 2004 Pennsylvania decided to authorize casinos and revive its horse-racing industry. Now the state has more than a dozen casinos, some stand-alone and some combined with resorts or race tracks. Erie’s Presque Isle Downs and Casino, which is named for the peninsular state park that juts out into Lake Erie but which is located off the Interstate just south of town, is a combined race track/casino. It has been open for about eight years.

For better or worse, nearly all states now allow casinos. (The two staunchest anti-gambling hold-outs are Utah and Hawaii, which don’t even allow lotteries. A few other states and jurisdictions, including Washington D.C., permit lotteries but not other forms of “gaming” businesses. Most everywhere else, place your bets!) Across the country we’ve seen the variety of ways in which the flow of resulting revenues is controlled. Some money goes to moguls: the Adelsons, Wynns, Trumps. Some, to the tribal authorities that run casinos in many states. Some, straight to state or county authorities, as in the unusual State of Kansas-owned Boot Hill Casino we saw in Dodge City. Virtually all lottery and casino schemes devote at least some of their money to schools or some other public-benefit purpose.

What is notable in Erie’s case is the way the community has decided to use its share of the casino revenues. It’s different from what we’ve seen any place else, and I think it deserves attention.

The short version of a complex story is that 1 percent of the Presque Isle complex’s total revenues come back to Erie County; half of that goes to retire bonds for airport expansion and other big-infrastructure projects; and the other half, totaling roughly $5 million per year, goes through ECGRA for use toward the general goal of regional economic development. This share was about about $1 million a year higher until neighboring Ohio opened casinos recently and drew off some of Presque Isle’s traffic. Thanks, Kasich!

The system ECGRA has evolved might look unfamiliar to many gaming-revenue authorities, but it would be immediately recognizable to many of the economic-development and civic-rebuilding strategists we’ve seen in places from Fresno and Riverside in California, to Bend, Oregon, to Greenville, South Carolina. That is, Erie has matched a familiar source of money (gambling) with a widespread civic goal (economic and technical renewal), in a novel and apparently successful way.

“The structure of our gaming-revenue commission is unique, in having the flexibility to use the money for economic development,” Perry Wood, who grew up not far from Erie in the town of Franklin and has been ECGRA’s director for the past five years, told us at his office in Erie on our first day in town. “We’re asking ourselves, What can we do to shape the future of this community? What can we do to make it more attractive to young people? What will make Erie a more vital community?”

After a while in Erie we began to recognize the work that terms like vital and future and attracting young people play in the discourse by Wood and his age-30-something contemporaries in Erie. At first glance, as I suggested here, Erie seems to illustrate just the opposite. The population has long been shrinking; many of the factories look shuttered and closed; the historic downtown is in obvious “pre”- rather than “post”-rebirth stage (as discussed here); and compared with the rest of the country and even the state, its people are on average old and poor.

That’s why it was so impressive to find a group of next-generation Erieites—those who never expected to get a lifetime job at the giant GE locomotive plant and therefore aren’t devastated as GE keeps shifting those jobs to Texas, those who look at the inexpensive real estate and still-present manufacturing infrastructure and see possibilities opening rather than closing—who think they can make this the next hot, successful city. The Erie Reader, a successful print publication (in the model of Seven Days in Burlington, which I wrote about three years ago), publishes an annual “40 Under 40” index of young business, cultural, and civic figures who have chosen to make something happen here.

As a community-journalism conceit this too is familiar. But I bet if you were driving past Erie on the interstate, and perhaps remembering Donald Trump’s recent appearance there to lament its lost glory days and tell his crowd that things were terrible in Erie as they were in the country as a whole, you would not imagine how strong a network of hopeful-seeming younger people was there. We’ve reported on similar trends in the also-hard-pressed San Bernardino; in Charleston, West Virginia; among the aspiring artistes of Fresno; and of course in the “Golden Triangle” of Mississippi. Around the country, the tension between trends that are objectively bad—economic, political, cultural—and the people trying to respond has been a continuing surprise of our reporting.

What does this mean, in specific, for ECGRA? You can read the organization’s latest annual report here, and see their history here, which includes official descriptions of their five focus areas. It describes them as: Quality of Place, efforts generally related to the national “place making” movement; Municipalities, improving cooperation among the crazy-quilt of public authorities that vex governance across Pennsylvania and that have overlapping impacts in the Erie area; Youth & Education, dealing with the unique structural-funding crisis for the city of Erie’s public schools (about which more in a later dispatch); Small Business, a kind of tech startup program; and Neighborhoods & Communities, for civic engagement of various sorts.

In specific, according to Perry Wood, this includes projects like:

- “Ignite Erie,” an across-the-board tech-startup initiative designed to connect universities, technical colleges, entrepreneurs, and financiers to foster new businesses in the inner-city areas. This is a sort of collaboration we have seen succeed in many other areas.

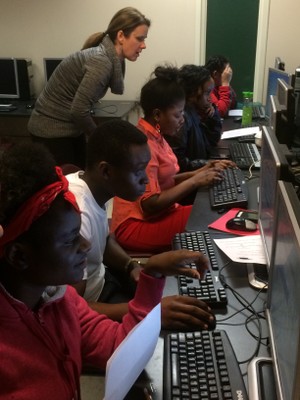

. - “Tech After Hours,” which allows displaced workers, adults, and others to use school-system facilities after the regular school day, for training as welders, machinists, builders, and other high-wage skilled trades.

. - A youth summer-jobs program, which this year hired some 170 people from ages 16 to 19 in construction and landscaping jobs “that give them both an income and some ‘soft-skills’ training,” Wood said.

ECGRA’s web site is quite comprehensively detailed, so you can learn about the range of other programs there. But the nitty-gritty of its operations, which I’ve only begun to learn about, are not really my subject or the reason I mention ECGRA.

Instead my points for now involve creativity, and appearances.

Creativity, in that a place rarely studied as a national trends-setter has devised a novel way of matching a phenomenon of this era (casinos) with a need of the era (recovery in sites of old-industrial decline).

And appearances, in the surprising complexity and energy happening just out of view.

“You probably saw all those closed-looking factories along 12th Street, on your way here,” Wood told us when we first met him, after our drive from the Tom Ridge Airport. (Ridge, former governor and Homeland Security secretary, is a local.) “We sure did,” I said. “It looks bad.”

We’d walked into Wood’s trap: “What you don’t know is that behind nearly every one of those facades that look closed, there is some kind of machine that is humming or forklift being operated. There is essentially no available industrial space on that corridor.”

I asked him what the guiding “myth” of the Erie area was—how people there think of themselves.

“We are hardy people, and we make stuff. We’ve exported our products around the world. Unfortunately, we’ve also exported talented young people, and that is what we believe we can change.”

One more note on perspective: After an item last month on people working to reverse Erie’s fortunes, I got into a polite-but-sharp Twitter exchange initiated by Chris Arnade. Arnade is a decades-long Wall Street trader, originally trained as a physicist, who in 2012 left Wall Street to see cities like the ones Deb and I have visited. In a series of photos, he has starkly documented the people most cruelly harmed, left behind, and broken by the technological dislocations, rich-vs-poor extremes, and new waves of drug-addiction during this Second Gilded Age.

Why, he asked, did he see and highlight what he did in his towns, and I saw and highlighted what I did?

The real answer, I expect, is that both of us see the range from promise to despair—and also believe that recognizing the full extent of that range is important for facing the reality of our times. During the Great Depression, it mattered that Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and others gave unforgettable human faces to the suffering across the country. It also mattered that people were figuring out which parts of the WPA or the CCC were making a difference and how they could be expanded.

Today it matters that people like Arnade are documenting the human stakes of ongoing modern injustices. It also matters that today’s Americans understand the efforts of people working toward greater justice and opportunity—and where and how they are making progress. All parts of today’s contradictory realities matter; Deb and I are chronicling aspects we feel are much less well-known than they should be. The sources of despair, and of hope, are both important elements in the story of our times.