Donald Trump likes to sort the world into winners and losers, which isn’t a bad way of thinking about democracy. Winners and losers of elections have essential responsibilities in functioning democracies. Winners do not exact revenge on their opponent by, say, abusing the powers of their office and jailing that opponent, as the Republican candidate threatened to do at the second presidential debate. Losers do not refuse to accept the results of a vote judged free and fair by a country’s governing institutions.

Yet the Republican candidate has spent the past week—really, much of the general election—strongly suggesting that he will not accept a loss to Hillary Clinton. He has repeatedly claimed that “Crooked Hillary” is “rigging” the election with help from the media and a global network of power brokers. The rigging, he says with certainty but no compelling evidence, consists of the coordinated assassination of Trump’s character, as well as looming voter fraud. And the rigging will, in Trump’s telling, produce nothing less than the dissolution of the republic; the United States will be overrun by immigrants and ISIS. Trump’s message is that the election will be stolen from his supporters, as will the country. Many Trump supporters expect this outcome; roughly half aren’t confident that ballots will be accurately counted on Election Day.

Donald Trump’s loose talk of imprisoning Clinton and his preemptive rejection of the election’s outcome pose one of the most serious challenges to U.S. democracy in recent memory. They endanger the “democratic bargain,” to quote the authors of Losers’ Consent: Elections and Democratic Legitimacy. That study examines how losing works in democracies around the globe, and the bargain at issue “calls for winners who are willing to ensure that losers are not too unhappy and for losers, in exchange, to extend their consent to the winners’ right to rule.” This bargain is also one of the core components of democracy.

On Friday, one of the authors of the study, the political scientist Shaun Bowler, applied his team’s findings to Trump’s warnings about a rigged election. “[G]raceful concessions by losing candidates constitute a sort of glue that holds the polity together, providing a cohesion that is lacking in less-well-established democracies,” Bowler wrote in Vox. Public-opinion surveys from around the world, he noted, indicate that winners and losers interpret the outcome of elections differently. Supporters of losing candidates tend to lose faith in democracy and democratic institutions, even after elections that aren’t particularly contentious. When your preferred politician or party loses, in other words, resentment is inevitable.

This is why the democratic bargain is so important: Winners do not suppress losers, which means losers can hope to be winners in the future. As a result, the losers’ doubts about the legitimacy of the political system gradually recede as they prepare for the next election.

But if the losing candidate doesn’t uphold his or her side of the bargain by recognizing the winner’s right to rule, that acute loss of faith in democracy among the candidate’s supporters can become chronic, potentially devolving into civil disobedience, political violence, and a crisis of democratic legitimacy. How the loser responds is especially critical because losers naturally have the most grievances about the election.

“[I]n the aftermath of a loss, there is plenty of kindling for irresponsible politicians to set fire to,” Bowler notes. “Most politicians who lose elections recognize this potential for mischief, and so they ordinarily make a creditable run at helping to keep matters calm.”

All losing presidential candidates in modern U.S. history have avoided the temptation to fan the flames of grievance, and have instead shown restraint and respect for the peaceful transfer of power. Many Americans take this norm for granted, and it can operate in subtle ways.

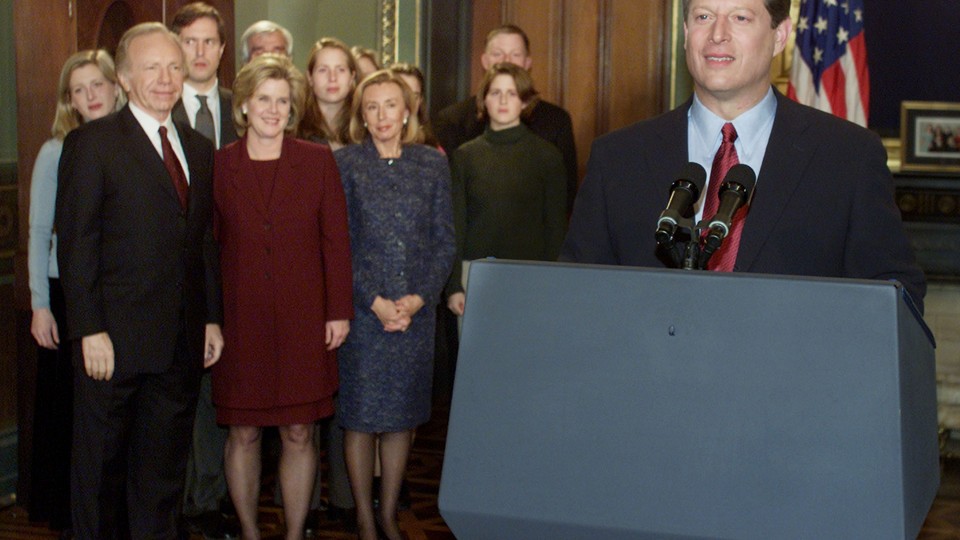

In December 2000, for example, Al Gore conceded defeat to George W. Bush after one of the country’s closest and most divisive elections. The Supreme Court halted the recount of votes in Florida and effectively handed the presidency to Bush, even though Gore won the national popular vote and had good reason to argue that the court’s decision was politically motivated.

To understand what it means to prioritize a political system over any one aggrieved politician—to put country before party or personal ambition despite the pressures to do otherwise—consider the statement that then-President Bill Clinton issued after Gore, his vice president, acknowledged Bush’s right to rule. Early drafts of the statement accepted the Supreme Court’s decision and congratulated Bush. But as Philip Bump noted in The Atlantic, those drafts also mentioned that “tens of thousands of ballots that may have decided a close election were never tallied,” that “[e]very American should have equal access to the ballot box,” and that Gore had fought “for the integrity of American democracy.”

By the time Clinton’s statement was delivered, all those bitter complaints had been removed from the text, save for brief mentions of disagreement with the court’s ruling and the need for bipartisan election reforms. Clinton’s team clearly recognized that it was time to put out fires, not to leave kindling lying around. “President-elect Bush and Vice President Gore showed what is best about America,” Clinton said. “In this election, the American people were closely divided. The outcome was decided by a Supreme Court that was closely divided. But the essential unity of our Nation was reflected in the words and values of those who fought this great contest.”

Gore later noted that he easily could have defied the court’s decision, but that he made the excruciating choice not to for the good of the country. “[I]nstead of making a concession speech, [I could have] launched a four-year rear guard guerrilla campaign to undermine the legitimacy of the Bush presidency, and to mobilize for a rematch,” he told The Washington Post in 2002. “And there was no shortage of advice to do that. I don’t know—I felt like maybe 150 years ago, in Andrew Jackson’s time, or however many years ago that is, that might have been feasible. But in the 21st century, with America the acknowledged leader of the world community, there’s so much riding on the success of any American president and taking the reins of power and holding them firmly, I just didn’t feel like it was in the best interest of the United States, or that it was a responsible course of action.”

Gore chose to adhere to the democratic bargain. It’s this norm that explains why, in a recent ranking of democratic elections in 139 countries, the United States performed well in terms of peacefully and legally resolving post-election disputes, even as it scored poorly on other metrics like money in politics. It’s this norm that moved Trump’s running mate, Mike Pence, to emphasize on Sunday that “We will absolutely accept the result of the election,” and it’s this norm that should move other Republican leaders, especially those who still support Trump, to unequivocally do the same ahead of Election Day and in the event that Trump loses the race. Asked whether he would accept the election’s outcome during the first presidential debate in September, Trump initially dodged the question before suggesting that he would. Chris Wallace, the moderator of the third and final debate, would do well to ask Trump again. And again.

What’s at stake in this election isn’t just a Clinton presidency or a Trump presidency. It’s America’s long political tradition of graceful losing. “I’ve always believed that U.S. election campaigns are, at the end of the day, incredibly civil,” the Indian journalist Chidanand Rajghatta, who’s been covering U.S. politics since 1994, told me earlier this year. “When it’s all over, there’s this remarkable healing that takes place on all sides. At least so far there’s been a lot of grace.”

“I don’t know whether that will apply to this election,” Rajghatta continued. “I wonder if this is a pivotal moment where grace goes out the window in U.S. politics.”