White-Washing Malcolm X: The Atlantic's View in 1965

A psychoanalytic interpretation of the slain civil-rights leader from shortly after his death

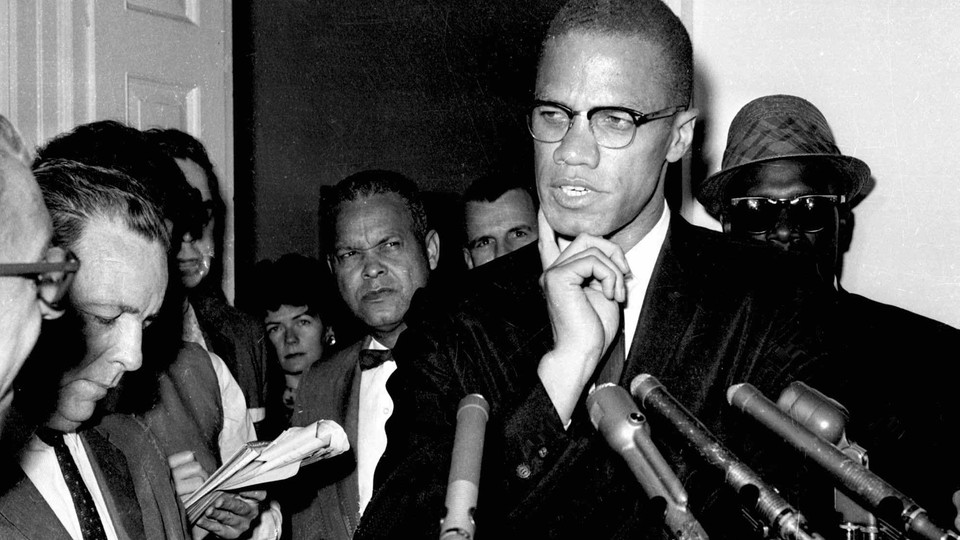

It has been nearly a half-century—49 years Friday—since three gunmen rushed Malcolm X at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem and killed him. The battle over his legacy, begun before his body was buried and fed with the posthumous release of his Autobiography several months later, rages still. Depending on one's viewpoint, he is a true hero or a tragically flawed one; a race-baiter; an inspiration; and even the subject of lurid conspiracy theories. Perhaps more than anything, he's rolled out as a foil to Martin Luther King—the more aggressive, militant yang to King's yin.

When the Autobiography was released, Pulitzer Prize-winning Harvard historian Oscar Handlin reviewed it in The Atlantic's December 1965 issue. Interestingly, Handlin sidestepped many of the broader social questions that the book and the man raised. You won't find any views on black Islam, segregation, militancy, or Sunni orthodoxy here; nor will you hear much of a theory about race in America. The story of Malcolm X, Handlin declared, is fundamentally about a broken person and a broken society. But what has broken them is not racism in American society but modernity (emphasis mine):

The Autobiography of Malcolm X is a moving and instructive account of a Negro whose involvement with the Black Muslim movement first gave meaning, and then destroyed, his life. The text was prepared with the assistance of Alex Haley, who fashioned it into a coherent book.

The perspective is that of Malcolm X, who sees himself as the white man's victim until he earns self-respect as a follower of Elijah Muhammad. The causes of the break with the prophet and of Malcolm's subsequent spiritual hegira are less clearly set forth.

Malcolm was not a product of the segregated South. His experience was Northern; he attended integrated schools and had frequent, indeed intimate, contact with whites. His bitterness, directed as much against middle-class Negroes as against whites, was a product not of separation but of the disorganization of his life. The death of his father contributed to his demoralization; but the chief factor in it was his inability to adjust to the conditions of existence of the modern city. Malcolm was the victim of the handicaps of race, but also of the burdens of the urban life of the past two decades.

It's not especially surprising that Handlin would situate Malcolm X as a victim of the contemporary urban landscape more than a victim of race, since the professor argued for a view of America in which citizens of all races were united by shared hardship. But it's also easy to see how such an argument would be appealing to the readership of a magazine founded by, and at the time still largely staffed and read by, educated white Northern readers who would have considered themselves progressive on race. It was straightforward for The Atlantic to criticize the segregated South; it was more problematic to have to grapple with Malcolm X's sharp polemic about the power of racism in the structures of integrated northern society. If his malady is modernity, however, suddenly he's not the angry face of black America.

Manning Marable's 2011 biography of Malcolm X—like the autobiography, published after the author's death—was a major landmark in studies of his legacy. Assessing that book in May 2011, Ta-Nehisi Coates laid out a rather different view:

For all of Malcolm’s prodigious intellect, he was ultimately more an expression of black America’s heart than of its brain. Malcolm was the voice of a black America whose parents had borne the slights of second-class citizenship, who had seen protesters beaten by cops and bitten by dogs, and children bombed in churches, and could only sit at home and stew. He preferred to illuminate the bitter calculus of oppression, one in which a people had been forced to hand over their right to self-defense, a right enshrined in Western law and morality and taken as essential to American citizenship, in return for the civil rights that they had been promised a century earlier. The fact and wisdom of nonviolence may be beyond dispute—the civil-rights movement profoundly transformed the country. Yet the movement demanded of African Americans a superhuman capacity for forgiveness. Dick Gregory summed up the dilemma well. “I committed to nonviolence,” Marable quotes him as saying. “But I’m sort of embarrassed by it.”