Last week, a group of Washington, D.C., parents and teachers stopped Betsy DeVos, the new secretary of education, from entering a D.C. middle school. Several conservative pundits compared DeVos, an outspoken school-choice advocate, to Vivian Malone and James Hood, the black students blocked from entering the University of Alabama by segregationists in 1963. The parallel, however, is somewhat problematic, since one of the things the D.C. parents were rallying against was segregation: The protester Betsy Wolf told NBC Washington she was there to ensure that DeVos “not do things to further the inequity and school segregation that already exists.”

As a new report from UCLA’s Civil Rights Project—a prominent critic of school choice—suggests, the protesters may have cause for concern. D.C.’s school district, despite being a darling of the school-choice movement, is intensely divided by both race and class, and the report’s authors, Gary Orfield and Jongyeon Ee, conclude that charter schools and vouchers may only be exacerbating the issue.

The researchers found that D.C. charter schools, which serve over 40 percent of the city’s student population, are more segregated than D.C.’s other public schools. In 2012, over two-thirds of charter schools, Orfield and Ee note, were “apartheid schools” (defined as having less than 1 percent white enrollment), whereas only 50 percent of public schools had such completely segregated populations. Voucher schools, another model that DeVos favors, often heightened this problem, according to the report, concentrating in affluent, white communities and underserving black families, who could often not afford to pay fees required beyond the vouchers themselves.

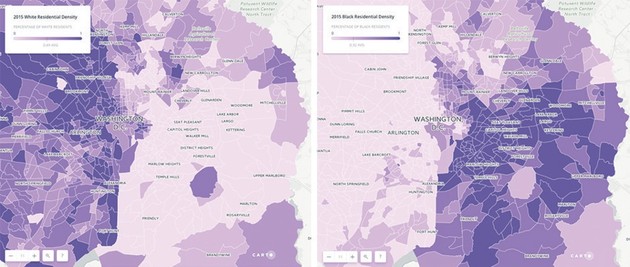

D.C.’s embrace of school choice began in earnest in the 1990s, but the city’s schools were segregated long before that. Underlying this is extreme housing segregation (and the hyper-racialized wealth inequality that feeds it). To better understand the scope of the issue, CityLab, a partner of The Atlantic, talked to Orfield about how education policies can help tackle the twin problems of housing and school segregation.

George Joseph: In both D.C. public and charter schools, white students are far more likely to be with other white students than a random distribution of the student population would have them be. Is this a simple story of extreme housing segregation, or are there other mechanisms at play?

Gary Orfield: There is an incredible income and jobs gap in D.C., and the housing costs in those neighborhoods tend to be impossible for many of the black families. D.C. has not used its subsidized housing policies to help with this problem, missing a key opportunity. D.C. has a larger unemployment racial gap than any state, which is, in part, the huge gap in educational achievement.

Joseph: It seems like school integration is almost impossible to enforce and make durable without accompanying moves to desegregate housing. What roles can schools play in this process, and what limits are there to a school-focused desegregation approach?

Orfield: The South’s mandatory countywide desegregation plans saw the highest and longest-lasting levels of desegregation. And there is strong evidence that it actually fostered more housing integration, since it removed most of the incentive for white departure and tended to create a level of integration that was widely acceptable across racial lines. But most of those plans dissolved following Supreme Court decisions in the l990s.

Joseph: Your report found that charter schools are significantly more segregated than traditional public schools. Why are D.C. charters so much more segregated, and what role has school choice played, if any, in preventing school desegregation in the district?

Orfield: Charters were created without the key mechanisms the magnet-school experience showed were essential. To achieving lasting diversity, you need to have recruitment across racial and ethnic lines, free transportation, a strongly appealing and distinctive curriculum, admission to all groups of students, integrated faculties, etc. School choice without such features almost always tends to stratify. Neighborhoods with schools that are already diverse or are mostly white and Asian don’t see the need for charters and often strongly support the local school.

Joseph: Could you expand on this more? How often do white and Asian families actually opt into school-choice programs in D.C.?

Orfield: Our stats show very few whites and Asians go into charter schools in D.C., and charters are very uncommon in affluent areas of suburbia. I always tell people, “If you really want to offer choice to poor students of color, why not the choice of your kids' schools rather than another segregated high-poverty school that no middle-class families choose?”

Joseph: You argue there is a collective action problem in creating strong stable schools integrated by race and class, especially because of fears that middle class students mixing with poorer students will hurt their achievement. Given these perceptions, what kind of serious desegregation options do schools have? Forced busing? Strong zoning to ensure diversity?

Orfield: There are various solutions to collective action problems. A mandatory framework proved to be very positive for the creation of successful magnet programs and other solutions, but it is rarely available since the Supreme Court’s Dowell decision in l991. The other solutions are leadership and incentives. If neighbors in a gentrified neighborhood can organize and find a way to foster and promote educationally successful integration, all the calculus can change. Or if the district or community organizers and institutions intervene positively in creating a strong attractive educational program with an explicit dedication to diversity, that can be a great help.

Sometimes it can become like the chemistry experiment where the conditions in a solution are right and drop in one crystal and the whole thing crystallizes. The great advantage is that if the offering changes and real diversity develops, it is something a great many people like and benefit from and it can well become self-sustaining.

This post appears courtesy of CityLab.