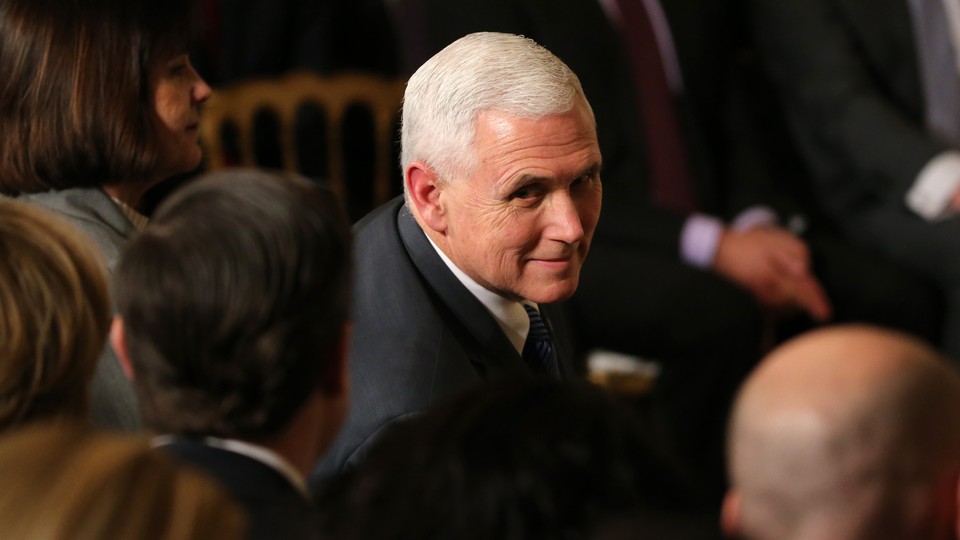

How Pence's Dudely Dinners Hurt Women

The vice president—and other powerful men—regularly avoid one-on-one meetings with women in the name of protecting their families. In the end, what suffers is women’s progress.

In a recent, in-depth Washington Post profile of Karen Pence, Vice President Mike Pence’s wife, a small detail is drawing most of the attention: “In 2002, Mike Pence told The Hill that he never eats alone with a woman other than his wife and that he won’t attend events featuring alcohol without her by his side, either.”

In context, this choice is not especially surprising. The Pences are evangelical Christians, and their faith animates both their policy views and how they express devotion to one another. Eight months into their courtship, the Post reporter Ashley Parker writes, “Karen engraved a small gold cross with the word ‘Yes’ and slipped it into her purse to give him when he popped the question.”

But, especially in boozy, late-working Washington, the eating thing rankled. Sure, during the day, you can grab coffee instead of a sandwich. But no dinner? Doesn’t that cut an entire gender off from a very powerful person at roughly 8 p.m.? To career-obsessed Washingtonians, that’s practically happy hour—which, apparently, is off-limits too.

3/ If Pence won’t eat with a woman alone, how could a woman be Chief of Staff, or lawyer, campaign manager, or...

— Clara Jeffery (@ClaraJeffery) March 29, 2017

Pence is not the only powerful man in Washington who goes to great lengths to avoid the appearance of impropriety with the opposite sex. An anonymous survey of female Capitol Hill staffers conducted by National Journal in 2015 found that “several female aides reported that they have been barred from staffing their male bosses at evening events, driving alone with their congressman or senator, or even sitting down one-on-one in his office for fear that others would get the wrong impression.” One told the reporter Sarah Mimms that in 12 years working for her previous boss, he “never took a closed door meeting with me. ... This made sensitive and strategic discussions extremely difficult.”

Social-science research shows this practice extends beyond politics and into the business world, and it can hold women back from key advancement opportunities. A 2010 Harvard Business Review research report led by Sylvia Ann Hewlett, the president of the Center for Work-Life Policy think tank, found that many men avoid being sponsors—workplace advocates—for women “because sponsorship can be misconstrued as sexual interest.”

Hewlett’s surveys, interviews, and focus groups found that 64 percent of executive men are reluctant to have one-on-one meetings with junior women, and half of junior women avoid those meetings in turn. Perhaps as a result, 31 percent of women in her sample felt senior men weren’t willing to “spend their chips” on younger women in office political battles. What’s more, “30 percent of them noted that the sexual tension intrinsic to any one-on-one relationship with men made male sponsorship too difficult to be productive.”

And that’s too bad, because according to the Harvard study and some others, women prefer male sponsors, perceiving them to be better-connected and more powerful. And they’re right: According to some analyses, men hold more than 85 percent of top management positions in big companies.

Because of that, when men avoid professional relationships with women, even if for noble reasons, it actually hurts women in the end. “The research is irrefutable: Those with larger networks earn more money and get promoted faster. Because men typically dominate senior management, there’s evidence that the most valuable network members may be men,” wrote Kim Elsesser, a research scholar at the UCLA Center for the Study of Women, in the Los Angeles Times recently. “Without access to beneficial friendships and mentor relationships with executive men, women won’t be able to close the gender gap that exists in most professions.”

Re the Mike Pence quote: Trying to imagine what my career would look like if I’d refused to dine solo with male editors & interview subjects

— Pamela Colloff (@pamelacolloff) March 30, 2017

Establishing cross-gender mentors, or even just office buddies, can be awkward. One study found that when mentors and their proteges are of different genders, they socialize less outside of work and their work relationships are harder to initiate because they worry others will misconstrue their friendliness as sexual interest. In a 2006 paper, Elsesser found that 75 percent of men in her sample worried about sexual harassment issues when interacting with woman at work, and 30 percent of participants had co-workers question them about the true motives behind a cross-gender friendship. In research Elsesser conducted for her recent book on the topic, some professional men and women told her they avoided dining with the opposite sex because they worried about the situation being misunderstood or didn’t want to upset their spouses. In psychology, this is known as the “audience challenge” to cross-gender friendships: People worry what their neighbors or co-workers are going to think.

But the way to overcome that problem, Elsesser said, is not to monastically order room service every night of your business trip. Instead, it’s to normalize men and women interacting professionally, in a non-sexual way. “If you always saw men and women meeting together for dinner,” she told me, “people wouldn’t see it as suspicious.”

In the midst of so much policy news, Pence’s gender-segregated meals might seem like a minor issue. And since that tidbit was from 2002, it’s not clear if he still hews to that standard. “He set a standard to ensure a strong marriage when he first came to D.C. as a congressman,” said Pence spokesman Marc Lotter in an email. “Clearly that worked.” Lotter pointed out that several members of Pence’s senior staff, including his deputy chief of staff, Jen Pavlik, and director of public engagement, Sarah Makin, are women.

But this quirk of Pence’s highlights broader questions over where, exactly, women’s voices—other than Ivanka Trump’s—belong in the Trump administration. Women I met while covering the Women’s March told me they feared, given Trump’s rhetoric, that their views and concerns will be pushed to the sidelines during his tenure. And indeed, Trump has vowed to defund Planned Parenthood and has already cut global family-planning funds.

As Jill Filipovic recently pointed out in The New York Times, “President Trump’s cabinet is the most white and male in 35 years. Among his top staff members, men outnumber women two to one.” When Pence tweeted a photo of a meeting with the House Freedom Caucus on health care recently, what made waves was not the attempts at political deal-making but the fact that room, which was weighing the elimination of mothers’ health benefits, was so crammed with Y-chromosomes.

A cheesy bon-mot popular among lobbyists goes, “in Washington, if you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.” In other words, if you don’t schmooze, you lose—and so does the agenda you’re pushing. If Pence literally won’t sit at the table with women, where does that leave women’s issues?

There’s really no need for Pence—or any other man—to wall women off professionally. As my colleague Emma Green points out, the Pence rule (which is actually the Billy Graham rule) is meant to preserve a marriage at all costs. But in the age of sexting, avoiding co-ed meetings seems aimed more at managing one’s reputation than at preventing a sex scandal. In 2017, if you really wanted to cheat on your wife, you wouldn’t take your staffer to the Palm. You’d hit her up on Snapchat.