How a Philly Ob-Gyn Ended Up Delivering a Baby Gorilla

“For the most part, I was in the moment, doing what I do every day.”

Last Friday, at 10:30 a.m., ob-gyn Rebekah McCurdy was seeing patients in her office when she got the call. Hello, said the voice on the line. It’s us. We’re thinking of doing a C-section, and we’re ready to put her under anesthesia. Weird, thought McCurdy. She wasn’t covering deliveries that morning, and in any case, she didn’t have any C-sections scheduled. “Who is this?” she said.

“It’s the zoo,” said the voice. “It’s for Kira.”

McCurdy dropped everything and ran to her car. A few hours later, she was delivering a baby gorilla into the world.

Philadelphia Zoo has a long history of raising great apes: In 1928, it became the first American zoo to successfully breed both chimpanzees and orangutans. In 2009, when it restarted its breeding program in a newly built primate house, vets contacted Stuart Weiner, a director at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and a specialist in high-risk obstetrics. They wanted someone on standby in case any of the pregnancies became complicated.

For a while, these precautions proved unnecessary. In 2009, Tua, one of the zoo’s Sumatran orangutans gave birth to a baby girl who was later named Batu. Seven years later, Honi, one of the two resident female gorillas also gave birth to a girl, who (after a public vote) was named Amani after the Swahili word for “peace.” Both pregnancies went smoothly. But when Kira, the second female gorilla, went into labor last Thursday, things took a different turn.

For gorillas, labor is not the obvious, painful process that it is in humans. Females will still move about, eat snacks, and do whatever it is that gorillas normally do. Their behavior is so normal that only trained observers can tell that something important is happening, which is why most gorilla births—even in captivity—are seldom recorded or witnessed. In this case, zookeepers noticed a few unusual signs. Kira started stretching her arms above her head and making squatting motions. Aha, they thought, she’s in labor. The process typically lasts from 6 to 12 hours, but by Friday morning, Kira still hadn’t given birth. More worryingly, she looked rather ill—she had become inactive, and she had lost interest in food. The zoo needed an ob-gyn.

Weiner was out of town but McCurdy, his colleague, had volunteered to act as a backup. She had visited the zoo when Honi was pregnant, so the gorillas were accustomed to her presence. She had read up on the reproductive biology of apes. “And I grew up on a farm so I’m used to animals,” she tells me. “But certainly not western lowland gorillas.”

After an anxious 20-minute drive, McCurdy pulled up at the zoo and was greeted by staff veterinarian Donna Ialeggio. She met the assembled team of vets and zookeepers, who decided to sedate Kira in preparation for a C-section. They hoisted her onto a stretcher, moved her out of the gorilla enclosure, and loaded her into a white van that must have temporarily doubled as the world’s strangest ambulance.

In a nearby building, McCurdy did an ultrasound. “We had to remove some of her fur so I could see; I don’t usually have to do that,” she says. “There were also bits of straw on her fur; that’s not usually a problem, either.” The ultrasound confirmed, for the first time, that there was indeed a baby—and just the one. Its heart rate was normal and it was head-down. But while gorillas typically deliver with the baby facing the front of the mother, this one was facing the wrong way round. Perhaps that was why Kira was having a hard time pushing it out.

Gorillas are clearly very different from humans. Their pelvis is both wider than ours, and larger relative to the baby. The babies are also proportionally smaller—a five-pound package coming out of a 260-pound mother. All of this makes birth much less difficult for gorillas, and females typically do so while crouching. As the newborn pops out, they quickly scoop it up and cradle it to their chest.

Still, gorillas are among our closest relatives, and their reproductive parts are similar enough to ours that McCurdy could easily apply all of her experience despite never having dealt with a non-human patient before.

She started with a pelvic exam—a procedure that, with human women, usually involves more conversation and explanation. But with McCurdy’s patient sedated (and, also, a gorilla), she narrated her findings to the assembled vets instead. To her surprise, Kira was on the cusp of delivery. “I remember looking at Donna and saying, Oh, she’s completely dilated. The baby’s right there,” she says. “One of the keepers behind me said, You sound like an obstetrician. I said, That’s because I am.”

The team was nervous about doing a C-section. Gorillas have been born in this way before, but the recovery period can be rough for such active, climbing animals. The team knew that once Kira was back in her enclosure, they wouldn’t be able to get close enough to check her bandages. They knew that Kira is a fidgety gorilla, with a habit of picking at scabs. And most of all, they weren’t sure what to do about the baby while she was recovering. Gorilla infants stay with their mothers for years, and the keepers didn’t want to disrupt those first critical moments, when the bond between mother and baby solidifies.

Ialeggio asked McCurdy what she’d do if the patient was a human. “I’d pull the baby out,” McCurdy said.

She hadn’t anticipated that when she left the hospital, so she hadn’t brought the requisite forceps along with her. The zoo had a variety of surgical equipment on hand but nothing that was exactly right. In the end, one of the more muscular vets bent a pair of retractors into the right shape.

The team, which by this point had swelled to include some surgeons and anesthesiologists from local hospitals, washed Kira and drained her bladder. They made a small nick in her perineum to give the baby more room. And then, McCurdy pulled.

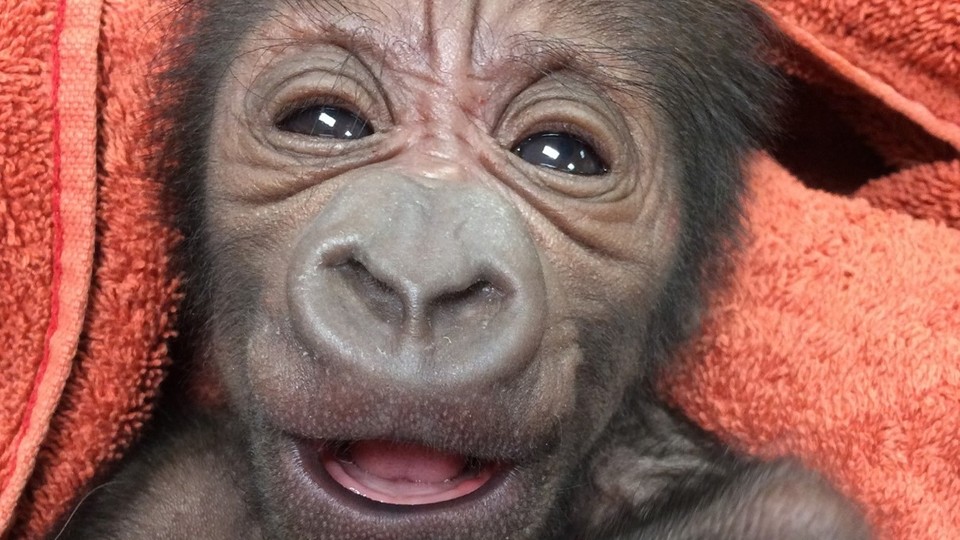

The baby—a five-pound boy—came out at around 1:58 p.m.

McCurdy placed it on a towel that Ialeggio was holding, and then paused before clamping its cord. Zoos don’t have blood banks for gorillas, so she wanted as much blood to get from the placenta to the baby as possible, in case anything should go wrong.

Fortunately, nothing did. The newborn was quieter than human babies, but it was clearly attentive and looking around. The staff gave Kira a night to recover from her sedation, and the next morning, they introduced her to her new baby. The two of them have been inseparable ever since. In time, the zoo will carry out another public vote to name their new arrival.

To have delivered a western lowland gorilla—a critically endangered ape with fewer than 100,000 individuals left in the wild—was an “incredible privilege,” McCurdy tells me. “For the most part, I was in the moment, doing what I do every day. It wasn’t until afterwards that it really hit me. Oh my, I believe I just delivered a gorilla.”

Not only that, but she happened to deliver a gorilla while being 28 weeks pregnant herself. Afterwards, McCurdy returned to the hospital to write up some notes and have a prenatal consultation. Then, she drove home to her husband and her three children.