The 1850s Response to the Racism of 2017

How the writers of The Atlantic responded to defenses of slavery in the 19th century

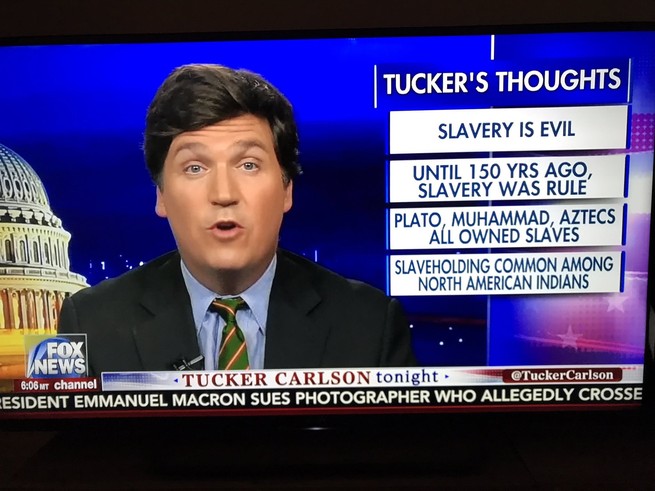

Last night, Tucker Carlson took on the subject of slavery on his Fox News show. Slavery is evil, he noted. However, slavery permeated the ancient world, he said, as reflected in the on-screen graphics.

On Twitter, recent University of Toronto English Ph.D. graduate Anthony Oliveira noted, “Here's Tucker Carlson right now on Fox making the *exact* pro-slavery case (bad but status-quo and well-precedented) made 160 years ago.”

It sounds like a particular variety of Twitter gallows humor, not meant to be taken quite seriously. But it is not a joke.

This precise series of ostensible mitigating factors around the institution of American slavery were, in fact, advanced by pro-slavery forces through the 19th century. And it got me wondering: Given that The Atlantic was founded as an abolitionist magazine before the Civil War, might there be an article or two that might address Carlson’s warmed-over proto-Confederate arguments?

And indeed, there are.

Take Carlson’s bullet point, “Until 150 years ago, slavery was rule.”

Well, yes. Slavery was legal in some American states. But how did this happen, especially when other countries began abolishing slavery early in the 19th century? In our second issue, Edmund Quincy put his pen to “Where Will It End?” And he doesn’t mess around. Slavers had power because they went on bloody conquests to open up new territory for slavery.

The baleful influence thus ever shed by Slavery on our national history and our public men has not yet spent its malignant forces. It has, indeed, reached a height which a few years ago it was thought the wildest fanaticism to predict; but its fatal power will not be stayed in the mid-sweep of its career ... Slavery presiding in the Cabinet, seated on the Supreme Bench, absolute in the halls of Congress—no man can say what shape its next aggression may not take to itself. A direct attack on the freedom of the press and the liberty of speech at the North, where alone either exists, were no more incredible than the later insolences of its tyranny ... The rehabilitation of the African slave-trade is seriously proposed and will be furiously urged, and nothing can hinder its accomplishment but its interference with the domestic manufactures of the breeding Slave States ... Mighty events are at hand, even at the door; and the mission of them all will be to fix Slavery firmly and forever on the throne of this nation.

Indeed, in the early days of The Atlantic, the violent battle over whether Kansas would become a slave state raged. In the “Kansas Usurpation,” from Issue 4, our author details the endless skulduggery that slavers perpetrated “to force the evils of slavery upon a people who cannot and will not endure them.”

And how about the idea that ancient peoples also held slaves? The Atlantic didn’t address Greek slaveholding, but takes on their admirers, the Romans. In a piece called “Spartacus,” published in Issue 3 in 1858, the author explicitly differentiates the Roman version of slavery from the American.

“Fowell Buxton has happily translated [the Roman motto], ‘They murdered all who resisted and enslaved the rest.’ But it was as slaveholders that the Romans most clearly exhibited their impartiality,” the piece states. “They were above those miserable subterfuges that are so common with Americans. They made slaves of all, of the high as well as the low—of Thracians, as well as Sardinians, of Greeks and of Syrians as readily as of Scythians and Cappadocians.”

With ever-increasing rigor from colonial times, the American system explicitly made only people with African ancestry subject to chattel slavery, i.e. they were the only people whose children were born enslaved and who would die enslaved, absent an extraordinary circumstance. American slavery was different.

To be clear, this isn’t just about Carlson. My target is the implicit idea that American slavery was not historically, distinctly terrible. It was. There is no parallel. While other countries—and states within the Union—were banning slavery, the South was intensifying slavery in several different ways.

First, the ideological and theological interpretation of slavery in the South began to change. The specific and perpetual enslavement of African people had seemed to Jeffersonian Americans as an evil that was ebbing away. “In the late 18th century, most Americans believed that slavery, as institutionalized dependence, was neither good nor practical, and so would fade before the action of natural forces under the new, free political system,” writes John Patrick Daly in When Slavery Was Called Freedom: Evangelicalism, Proslavery, and the Causes of the Civil War.

But as abolitionists began to succeed in the northern states, chattel slavery of black human beings began to be theologically promoted as something to be proud of, possibly even holy, in the South. “Good slaveholders, they maintained, gave the institution its character—that is, goodness,” Daly writes. “This formulation allowed proslavery spokesmen to denounce the historically evil institution of slavery while defending Southern practices: Slaveholders in the evil form of slavery were bad men; the Southerners were good, and the source of their wealth untainted. Good—and especially evangelical—slaveholders supposedly redeemed the institution of slavery.”

Second, the old colonial state slaveowners were making a business out of selling the people they enslaved south and west. This became a lynchpin of the region’s wealth as agriculture declined there. Black people were chained together in Virginia and the Carolinas and marched to Georgia, to Florida, to Mississippi, to Texas. Whatever networks of family and community they’d been able to build within the oppressive violence of slavery were destroyed (again).

Ed Baptist tells this story in The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. “The massive and cruel engineering required to rip a million people from their homes, brutally drive them to new, disease-ridden places, and make them live in terror and hunger as they continually built and rebuilt a commodity-generating empire,” he writes, “this vanished in the story of a slavery that was supposedly focused primarily not on producing profit but on maintaining its status as a quasi-feudal elite, or producing modern ideas about race in order to maintain white unity and elite power.”

Third, the gin-powered cotton economy relied on huge financial investments to open up new cotton land ever farther south and west. A series of financial bubbles ran in those directions, with literal securities issued to slaveowners secured by the bodies of enslaved people.

“African American bodies and childbearing potential collateralized massive amounts of credit, the use of which made slaveowners the wealthiest people in the country,” write Ned and Constance Sublette in The American Slave Coast: A History of the Slave-Breeding Industry. “When the Southern states seceded to form the Confederacy they partitioned off, and declared independence for, their economic system in which people were money.”

To make their loan payments, these speculator-slavers created the brutal “whipping machine,” which drove massive productivity gains at the expense of the health and well-being of the already oppressed people working in the fields.

”The returns from cotton monopoly powered the modernization of the rest of the American economy, and by the time of the Civil War, the United States had become the second nation to undergo large-scale industrialization,” Baptist writes. “In fact, slavery’s expansion shaped every crucial aspect of the economy and politics of the new nation—not only increasing its power and size, but also, eventually, dividing U.S. politics, differentiating regional identities and interests, and helping to make civil war possible. The idea that the commodification and suffering and forced labor of African Americans is what made the United States powerful and rich is not an idea that people necessarily are happy to hear. Yet it is the truth.”

It was this marriage of new ideological underpinning, the incredible profits the gin-powered cotton industry could produce, and the new modes of capitalization and management that American slaveowners developed that make American slavery different and worse from those that preceded it.

The drive to keep opening up cotton land to feed the slaver-speculator economy also led to genocidal atrocities against Native Americans, as well as the imperial project of snatching the western part of the continent from Mexico, which had abolished slavery in the 1820s.

In April 1861, with the slaveholder’s rebellion beginning, The Atlantic published an essay by Charles Francis Adams Jr., the grandson of John Quincy Adams, called “The Reign of King Cotton.”

“Throughout the South, whether justly or not, it is considered as well settled that cotton can be profitably raised only by a forced system of labor,” Adams wrote. “With this theory, the Southern States are under a direct inducement, in the nature of a bribe, to the amount of the annual profit on their cotton-crop, to see as many perfections and as few imperfections as possible in the system of African slavery.”

But the bribe didn’t stop getting paid at the Mason-Dixon line. Even New England, hotbed of abolitionism and birthplace of this magazine, got rich on textiles spun in the factories along the Merrimack. Where do you think they got the cotton for the City of Spindles? Baptist tells the story of the Collins Axe Works, which sold hundreds of thousands of axes into the western parts of the South, where they were given to enslaved black people to clear the forests. Hundreds of millions of trees fell through black labor performed with these axes. And back on the Farmington River, a white factory owner and his associates got rich.

“All told, more than $600 million, or almost half of the economic activity in the United States in 1836, derived directly or indirectly from cotton produced by the million-odd slaves—6 percent of the total U.S. population—who in that year toiled in labor camps on slavery’s frontier,” Baptist calculates.

There is no escaping the basic facts of our history. Plato, Muhammad, and the Aztec empire did not have the cotton gin or the luxuries that came from the securitization of enslaved people. Native American slaveholders didn’t shape and take advantage of emergent American capitalism to subdue a continent.

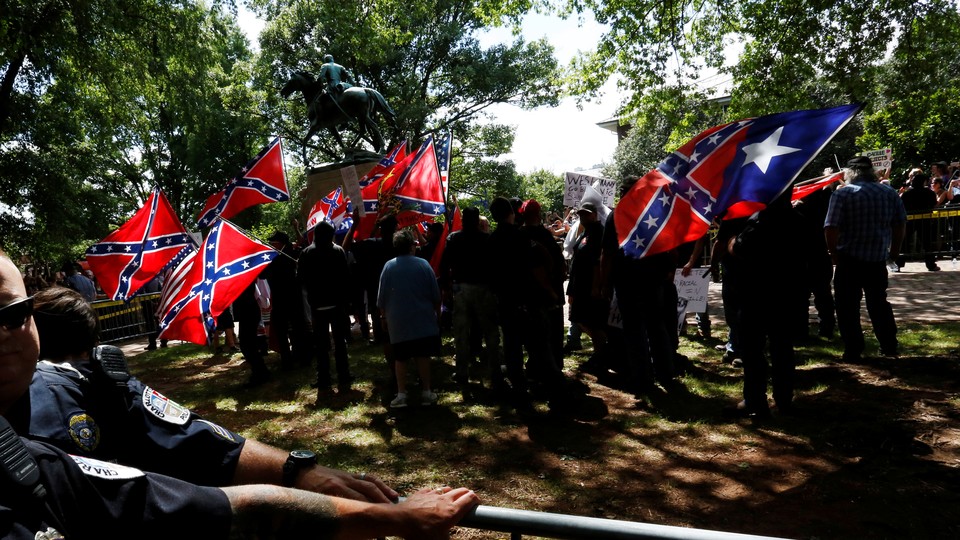

Given all this, no wonder the neo-Confederates keep fighting to keep their heroic monuments. Understanding the breadth and depth of the American slavery’s evil would undermine not just their dedication to busts of Robert E. Lee, but the whole moral project of seeing whiteness as a sign of virtue.

This is what Confederate flag wavers mean when they say they are “fighting for their heritage.” They are fighting for the right to declare their ancestors good, despite the evidence of the horrors they perpetrated, which rival anything that happened in the 20th century.

And what they’re counting on is that Americans, no matter when their families arrived across seas or rivers, will excuse the Confederate flag-wavers because they want to believe only the best stories about our country, too.

There is no excuse. That other people at other times owned slaves—Greek, African, or Native American—does not excuse the system of oppression that we erected on this continent to build this country.

“Many of those people were there to protest the taking down of the statue of Robert E. Lee. So this week, it’s Robert E. Lee, I noticed that Stonewall Jackson’s coming down,” President Trump said yesterday at a press conference. “I wonder, is it George Washington next week? And is it Thomas Jefferson the week after? You know, you really do have to ask yourself, where does it stop?”

What if the answer is that it doesn’t? The evil of slavery and the white supremacy it embedded in the fabric of the country go all the way back to the beginning. And our history needs to honestly tell the story of James Madison dying without freeing a single one of the 100 enslaved people who worked for him right alongside his call, quoted in The Atlantic in 1861, to leave the words slavery out of the Constitution so that it would “be the great charter of Human Liberty to the unborn millions who shall enjoy its protection, and who should never see that such an institution as slavery was ever known in our midst.”

We can excise the words, but we can never scrub the blood from the soil.