Giving to Charity via Unlikely Middlemen: Walmart and Coke

A fledgling company asks: Is activism compatible with profitable investments?

Liam Monaghan, a 37-year-old white South African who now lives in California, knows from personal experience that making the world a better place can come at the expense of one’s own security and freedom. His aunt and uncle, Eve and Tony Hall, joined the anti-apartheid African National Congress in 1961, one year after the South African police opened fire on a crowd of black protesters and killed 69 people. The Halls were eventually arrested and expelled from the country. But, fortunately for Monaghan, he seems to have figured out how to do his part in a way that is both less dangerous and more profitable.

Monaghan is one of the founders of Swell Investing, a new financial-research company guided by the philosophy that “you can do well for yourself and do good for those in need at the same time.” It’s not a novel concept: There are plenty of powerful organizations such as the Rockefeller Foundation and Morgan Stanley’s Institute for Sustainable Investing exhibiting a similar spirit.

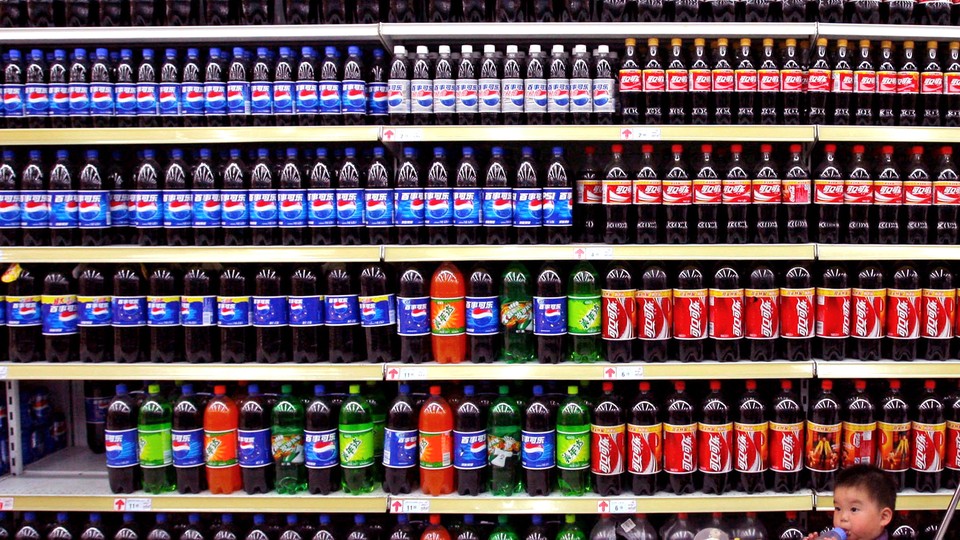

But what is novel is that money invested in Swell, before it finds its way to a microfinance agency in India or a builder of low-cost irrigation systems in Kenya, usually passes through some unlikely middlemen: relatively large corporations, such as Walmart and Coca-Cola.

Swell essentially connects investors with companies that give a lot of money to charity, and has partnered with Motif Investing, a socially-minded online brokerage, to facilitate this. The way Swell works is fairly simple: For a flat fee of $9.95 and a minimum investment of $250, people can choose one of Swell’s four distinct investment areas, each dedicated to a different “motif”: “improving education,” “upholding human rights,” “fighting cancer,” and, most ambitiously, “ending poverty.”

Say a person is particularly concerned about human rights. If he or she checks the box for that “motif,” his or her money will be parceled out among about 30 different companies that Swell has identified as major players in the world of human-rights philanthropy. Crucially, these companies have been selected not just for charitableness, but also for profitability. In other words, Swell isn’t asking people to just give money to charity—it’s offering a way to make money by giving to charity. As an added incentive, Swell also pledges 20 percent of its own revenues to those same charities.

Monaghan and his co-founder, Dave Fanger, came up with the idea for Swell in 2012, somewhere in the sky between Los Angeles and New York. They were on a business trip for Pacific Life, a life-insurance company where they were working as actuaries, and at some point their conversation turned to a new trend in investing—the idea of “doing well by doing good.” At first, they were skeptical. “There's a lot of marketing out there about companies giving back,” said Monaghan. “We are investment geeks. We wanted to look at their performance.”

So they dove into the data, poring over tax records to determine which of the largest publicly-traded companies in the U.S. were backing up their philanthropic talk with action. After that, they approached their bosses with a pitch.

It turned out to be an easy sell. Unlike Swell, Pacific Life has been around for more than 100 years; its founder and first policyholder was Leland Stanford, who also founded Stanford University. In 2012, the company was looking to expand its clientele to include more young people—and young people, as recent surveys have shown and as Monaghan and Fanger are quick to point out, are more likely than their parents and grandparents to care about the social impact of their investments. “Pacific Life recognized that,” said Fanger, “and agreed.” (Swell is a subsidiary of Pacific Life.)

Although charitable donations might address society’s problems more directly, Swell has certain advantages, Monaghan argues. For one thing, the barrier to using it is relatively low: The $250 minimum investment is a pittance compared with the $2,500 minimum required of some social-responsibility-oriented mutual funds. Then there’s the fact that a client can customize each investment to suit his or her preferences, which isn’t possible with a mutual fund. Worried about how sugary beverages are affecting the health of the kids whose education you’re supporting? You’re free to remove Coca-Cola from your portfolio.

Monaghan wouldn’t disclose Swell’s revenue figures or client numbers, though he did note that its returns have been tracking with the S&P 500. But even if Swell’s figures were made public, there’d still be the problem of measuring its humanitarian progress. Swell is “a good thing,” said Robert Strand, the executive director for the Center for Responsible Business at UC Berkeley. “That said, I am a bit leery to assess the social impact of a company solely upon the dollars that it donates. I feel that it is even more important to assess how a company makes its money, not just how it spends it.”