How a Genealogy Website Led to the Alleged Golden State Killer

Powerful tools are now available to anyone who wants to look for a DNA match, which has troubling privacy implications.

Updated on April 27 12:45 p.m. ET.

When the East Area Rapist broke into the home of his first victim in 1976, human DNA had not yet been sequenced. When he reemerged as the Original Night Stalker and began a spree of murders in 1979, the World Wide Web still did not exist. For decades, the Golden State Killer—as he is now best known—got away with it all.

Then DNA and the internet appear to have caught up. Reporting from The Sacramento Bee and Mercury News indicates that police arrested Joseph James DeAngelo based on DNA found at crime scenes that partially matched the DNA of a relative on the open-source genealogy website GEDmatch. Previous searches of law-enforcement DNA databases had turned up no matches.

This way of finding people by DNA is new to law enforcement, but it is not new to genealogists, who immediately recognized their methods in the police’s vague descriptions. And the revelation has landed like a bomb. It at once demonstrates the power of genetic genealogy research and exposes the many ethical and privacy issues: Did any of DeAngelo’s distant relatives know their DNA could be searched by law enforcement? Will people want to upload their DNA to genealogy websites if it could one day incriminate their children—or their children’s children’s children?

“It’s very controversial,” says Margaret Press, a genetic genealogist who co-runs the nonprofit DNA Doe Project.“It’s going be debated for a very long time in law and forensics and genealogy and everywhere you can imagine.”

The Sacramento County district attorney’s office declined to comment, except to confirm the Bee’s reporting. Genetic genealogists, however, outlined to The Atlantic how the search was likely done. “The process is really your standard genealogy research project. It’s no different from finding an adoptee,” says Press.

First, how it was not done. Direct-to-consumer DNA testing companies like 23andMe and AncestryDNA did not directly hand customer information over to police. Nor could law enforcement have sent DNA from the crime scene to these two companies, which require a large tube of saliva. Both 23andMe and Ancestry have denied being involved in the case.

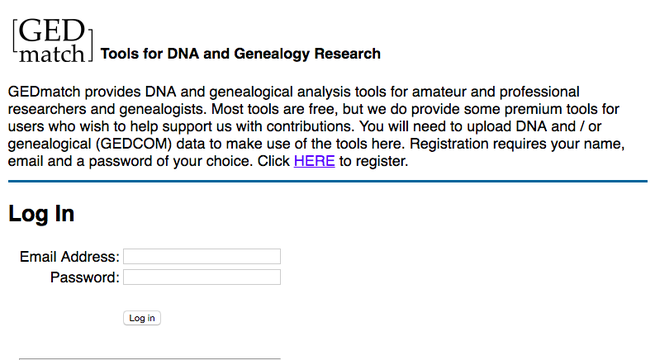

But customers can themselves choose to export the raw data file from these and other DNA-testing services to a third-party site, such as GEDmatch. These third-party sites are less user friendly than the websites of 23andMe or AncestryDNA, but they offer a more powerful suite of tools. For example, GEDmatch allows users to find profiles that match only one particular segment of DNA. It also lets users who have tested with different services match with each other without shelling out for another one. GEDmatch offers premium tools but is largely free to use.

It’s unclear how exactly law enforcement generated a profile of the Golden State Killer from DNA left at crime scenes. But the DNA Doe Project’s Press and her partner, Colleen Fitzpatrick, were recently able to identify Marcia King, murdered in 1981, after whole genome sequencing on a highly degraded DNA sample nevertheless matched to a first cousin once removed on GEDmatch.

GEDmatch is an example of the openness in the genealogy community, says CeCe Moore, a genetic genealogist. “We have amazing citizen scientists who have built tools the companies have not been able or willing to provide,” she says. “And we encouraged or demanded we have access to our raw data.” But this openness makes it easier for law enforcement to access data, too. Unlike 23andMe or Ancestry, GEDmatch does not have lawyers to protect the data of its users. The website issued a statement saying law enforcement did not directly approach the site about the research and urged concerned users to delete their registration.

“The police officer’s ability to throw some information into a public database like this is wholly unregulated,” says Erin Murphy, a law professor at New York University Law School. In 2014, a genealogical database search led police working a cold case to man in New Orleans, who turned out to be innocent. California also allows law enforcement to look for relatives in criminal-justice DNA databases—but those searches are regulated and restricted to certain serious crimes.

GEDmatch provides a more powerful way of tracing people by DNA and genealogy than a better-known method that only uses the Y chromosome. Fitzpatrick, Press’s partner in the DNA Doe Project, is an expert on this. In 2014, she tracked down the alleged “Canal Killer” in Phoenix, Arizona by matching the Y chromosome to a family name, which are both passed through fathers. Using age and location information, police then narrowed it down to a single man. However, this has severe limits, according to Fitzpatrick and Press. Y chromosomes cannot tell you how related two people are—even distant cousins with a last common ancestry in the 17th century may have essentially identical Y chromosomes. And, of course, it traces exclusively through the male line.

In fact, Fitzpatrick had tried using the Y chromosome to find the Golden State Killer. Michelle McNamara, the author of a recent book about his crimes called I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, consulted with Fitzpatrick after uploading his DNA profile to a Y chromosome database on Ancestry.com. The one match, however, was too distant to yield a useful lead.

“In this case, the Y chromosome definitely would not have led to him,” says Moore of the Golden State Killer case. “There’s much more power in autosomal DNA to resolve any sort of family or genealogical mystery.” Autosomal DNA refers to the DNA on the 22 pairs of other chromosomes that are not X and Y. With a web of enough matches or better yet one close match, an experienced genetic genealogist can begin to identify family members.

This work requires enough expertise that a professional genetic genealogist likely helped law enforcement—an idea that is deeply troubling to some in the community. “Because of the way this is done surreptitiously, there is also a lot of anger and backlash in our community,” says Press.

Press and Moore say they both know of genealogists making profiles on GEDmatch private after the Golden State Killer case became known. They fear that backlash from this case could make it harder for people trying to find family—or even police trying to find other suspects—in the future.

Given the power of genetic genealogy, a case like this was bound to come up. Even before it became public, Moore says, the community had been discussing a public statement about how law enforcement searches should be handled, but they could not agree. Now the debate has spilled out into the public.

“The question now is how we can work together so nobody’s privacy is invaded and it doesn’t damage our industry,” she says. “I would be devastated to see it come crashing down because of something like this.”