A Landslide of Classic Art Is About to Enter the Public Domain

For the first time in two decades, a huge number of books, films, and other works will escape U.S. copyright law.

The Great American Novel enters the public domain on January 1, 2019—quite literally. Not the concept, but the book by William Carlos Williams. It will be joined by hundreds of thousands of other books, musical scores, and films first published in the United States during 1923. It’s the first time since 1998 for a mass shift to the public domain of material protected under copyright. It’s also the beginning of a new annual tradition: For several decades from 2019 onward, each New Year’s Day will unleash a full year’s worth of works published 95 years earlier.

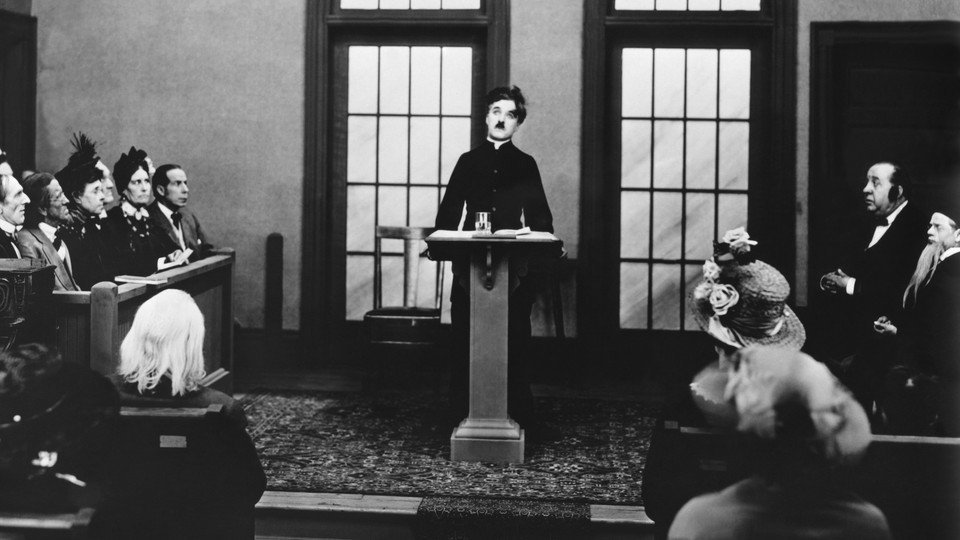

This coming January, Charlie Chaplin’s film The Pilgrim and Cecil B. DeMille’s The 10 Commandments will slip the shackles of ownership, allowing any individual or company to release them freely, mash them up with other work, or sell them with no restriction. This will be true also for some compositions by Bela Bartok, Aldous Huxley’s Antic Hay, Winston Churchill’s The World Crisis, Carl Sandburg’s Rootabaga Pigeons, e.e. cummings’s Tulips and Chimneys, Noël Coward’s London Calling! musical, Edith Wharton’s A Son at the Front, many stories by P.G. Wodehouse, and hosts upon hosts of forgotten works, according to research by the Duke University School of Law’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain.

Throughout the 20th century, changes in copyright law led to longer periods of protection for works that had been created decades earlier, which altered a pattern of relatively brief copyright protection that dates back to the founding of the nation. This came from two separate impetuses. First, the United States had long stood alone in defining copyright as a fixed period of time instead of using an author’s life plus a certain number of years following it, which most of the world had agreed to in 1886. Second, the ever-increasing value of intellectual property could be exploited with a longer term.

But extending American copyright law and bringing it into international harmony meant applying “patches” retroactively to work already created and published. And that led, in turn, to lengthy delays in copyright expiring on works that now date back almost a century.

Only so much that’s created has room to persist in memory, culture, and scholarship. Some works may have been forgotten because they were simply terrible or perishable. But it’s also the case that a lack of access to these works in digital form limits whether they get considered at all. In recent years, Google, libraries, the Internet Archive, and other institutions have posted millions of works in the public domain from 1922 and earlier. With lightning-fast ease, their entire contents are now as contemporary as news articles, and may show up intermingled in search results. More recent work, however, remains locked up. The distant past is more accessible than 10 or 50 years ago.

The details of copyright law get complicated fast, but they date back to the original grant in the Constitution that gives Congress the right to bestow exclusive rights to a creator for “limited times.” In the first copyright act in 1790, that was 14 years, with the option to apply for an automatically granted 14-year renewal. By 1909, both terms had grown to 28 years. In 1976, the law was radically changed to harmonize with the Berne Convention, an international agreement originally signed in 1886. This switched expiration to an author’s life plus 50 years. In 1998, an act named for Sonny Bono, recently deceased and a defender of Hollywood’s expansive rights, bumped that to 70 years.

The Sonny Bono Act was widely seen as a way to keep Disney’s Steamboat Willie from slipping into the public domain, which would allow that first appearance of Mickey Mouse in 1928 from being freely copied and distributed. By tweaking the law, Mickey got another 20-year reprieve. When that expires, Steamboat Willie can be given away, sold, remixed, turned pornographic, or anything else. (Mickey himself doesn’t lose protection as such, but his graphical appearance, his dialog, and any specific behavior in Steamboat Willie—his character traits—become likewise freely available. This was decided in a case involving Sherlock Holmes in 2014.)

The reason that New Year’s Day 2019 has special significance arises from the 1976 changes in copyright law’s retroactive extensions. First, the 1976 law extended the 56-year period (28 plus an equal renewal) to 75 years. That meant work through 1922 was protected until 1998. Then, in 1998, the Sonny Bono Act also fixed a period of 95 years for anything placed under copyright from 1923 to 1977, after which the measure isn’t fixed, but based on when an author perishes. Hence the long gap from 1998 until now, and why the drought’s about to end.

Of course, it’s never easy. If you published something between 1923 and 1963 and wanted to renew copyright, the law required registration with the U.S. Copyright Office at any point in the first 28 years of copyright, followed at the 28-year mark with the renewal request. Without both a registration and a renewal, anything between 1923 and 1963 is already in the public domain. Many books, songs, and other printed media were never renewed by the author or publisher due to lack of sales or interest, an author’s death, or a publisher’s shutting down or bankruptcy. One estimate from 2011 suggests about 90 percent of works published in the 1920s haven’t been renewed. That number shifts to 60 percent or so for works from the 1940s. But there are murky issues about ownership and other factors for as many as 30 percent of books from 1923 to 1963. It’s impossible to determine copyright status easily for them.

It’s easier to prove a renewal was issued than not, making it difficult for those who want to make use of material without any risk of challenge. Jennifer Jenkins, the director of Duke’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain, says, “Even if works from 1923 technically entered the public domain earlier because of nonrenewal, next year will be different, because then we’ll know for sure that these works are in the public domain without tedious research.”

Jenkins’s group was unable, for instance, to find definitive proof that The Great American Novel wasn’t renewed, but that doesn’t mean there’s not an undigitized record in a file in Washington, D.C. While courts can be petitioned to find works affirmatively in the public domain, as ultimately happened following a knotted dispute over “Happy Birthday to You,” most of the time the issue only comes up when an alleged rights holder takes legal action to assert that copyright still holds. As a result, it’s more likely a publisher would wait to reissue The Great American Novel in 2019 than worry about Williams’s current copyright holders objecting in 2018.

There’s one more bit of wiggle, too: Libraries were granted special dispensation in the 1998 copyright revision over work in its last 20 years of its copyright so long as the work isn’t being commercially exploited, such as a publisher or author having a book in print or a musician actively selling or licensing digital sheet music. But hundreds of thousands of published works from 1923 to 1941 can be posted legally by libraries today, moving forward a year every year. (The Internet Archive assembles these works from partners at its ironic Sonny Bono Memorial Collection site.)

It’s possible this could all change again as corporate copyright holders start to get itchy about expirations. However, the United States is now in harmony with most of the rest of the world, and no legislative action is underway this year to make any waves that would affect the 2019 rollover.

A Google spokesperson confirmed that Google Books stands ready. Its software is already set up so that on January 1 of each year, the material from 95 years earlier that’s currently digitized but only available for searching suddenly switches to full text. We’ll soon find out more about what 1923 was really like. And in 2024, we might all ring in the new year whistling Steamboat Willie’s song.