I could have seen it only there, on the waxed hardwood floor of my elementary-school auditorium, because I was young then, barely 7 years old, and cable had not yet come to the city, and if it had, my father would not have believed in it. Yes, it had to have happened like this, like folk wisdom, because when I think of that era, I do not think of MTV, but of the futile attempt to stay awake and navigate the yawning whiteness of Friday Night Videos, and I remember that there were no VCRs among us then, and so it would have had to have been there that I saw it, in the auditorium that adjoined the cafeteria, where after the daily serving of tater tots and chocolate milk, a curtain divider was pulled back and all the kids stormed the stage. And I would have been there among them, awkwardly uprocking, or worming in place, or stiffly snaking, or back-spinning like a broken rotor, and I would have looked up and seen a kid, slightly older, facing me, smiling to himself, then moving across the floor by popping up alternating heels, gliding in reverse, walking on the moon.

Nothing happens that way anymore. Nothing can. But this was 1982, and Michael Jackson was God, but not just God in scope and power, though there was certainly that, but God in his great mystery; God in how a child would hear tell of him, God in how he lived among the legend and lore; God because the Walkman was still uncommon, and I was young and could not count on the car radio, because my parents lived between NPR and WTOP. So the legends were all I had—tales of remarkable feats and fantastic deeds: Michael Jackson mediated gang wars; Michael Jackson was the zombie king; Michael Jackson tapped his foot and stones turned to light. Even his accoutrements felt beyond me—the studded jacket, the sparkling glove, the leather pants—raiment of the divine, untouchable by me, a mortal child who squinted to see past Saturday, who would not even see Motown 25 until it was past 30, who would not even own a copy of Thriller until I was a grown man, who no longer believed in miracles, and knew in my heart that if the black man’s God was not dead, he surely was dying.

And he had always been dying—dying to be white. That was what my mother said, that you could see the dying all over his face, the decaying, the thinning, that he was disappearing into something white, desiccating into something white, erasing himself, so that we would forget that he had once been Africa beautiful and Africa brown, and we would forget his pharaoh’s nose, forget his vast eyes, his dazzling smile, and Michael Jackson was but the extreme of what felt in those post-disco years to be a trend. Because when I think of that time, I think of black men on album covers smiling back at me in Jheri curls and blue contacts and I think of black women who seemed, by some mystic edict, to all be the color of manila folders. Michael Jackson might have been dying to be white, but he was not dying alone. There were the rest of us out there, born, as he was, in the muck of this country, born in The Bottom. We knew that we were tied to him, that his physical destruction was our physical destruction, because if the black God, who made the zombies dance, who brokered great wars, who transformed stone to light, if he could not be beautiful in his own eyes, then what hope did we have—mortals, children—of ever escaping what they had taught us, of ever escaping what they said about our mouths, about our hair and our skin, what hope did we ever have of escaping the muck? And he was destroyed. It happened right before us. God was destroyed, and we could not stop him, though we did love him, we could not stop him, because who can really stop a black god dying to be white?

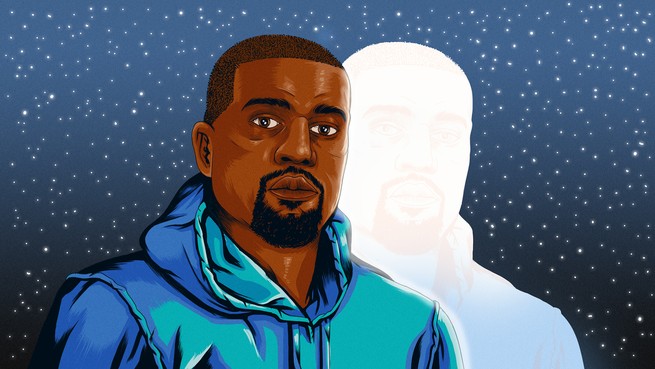

Kanye West, a god in this time, awakened, recently, from a long public slumber to embrace Donald Trump. He hailed Trump, as a “brother,” a fellow bearer of “dragon energy,” and impugned those who objected as suppressors of “unpopular questions,” “thought police” whose tactics were “based on fear.” It was Trump, West argued, not Obama, who gave him hope that a black boy from the South Side of Chicago could be president. “Remember like when I said I was gonna run for president?” Kanye said in an interview with the radio host Charlamagne Tha God. “I had people close to me, friends of mine, making jokes, making memes, talking shit. Now it’s like, oh, that was proven that that could have happened.”

There is an undeniable logic here. Like Trump, West is a persistent bearer of slights large and small—but mostly small. (Jay-Z, Beyoncé, Barack Obama, and Nike all came in for a harangue.) Like Trump, West is narcissistic, “the greatest artist of all time,” he claimed, helming what would soon be “the biggest apparel company in human history.” And, like Trump, West is shockingly ignorant. Chicago was “the murder capital of the world,” West asserted, when in fact Chicago is not even the murder capital of America. West’s ignorance is not merely deep, but also dangerous. For if Chicago truly is “the murder capital of the world,” then perhaps it is in need of the federal occupation threatened by Trump.

It is so hard to honestly discuss the menace without forgetting. It is hard because what happened to America in 2016 has long been happening in America, before there was an America, when the first Carib was bayoneted and the first African delivered up in chains. It is hard to express the depth of the emergency without bowing to the myth of past American unity, when in fact American unity has always been the unity of conquistadors and colonizers—unity premised on Indian killings, land grabs, noble internments, and the gallant General Lee. Here is a country that specializes in defining its own deviancy down so that the criminal, the immoral, and the absurd become the baseline, so that even now, amidst the long tragedy and this lately disaster, the guardians of truth rally to the liar’s flag.

Nothing is new here. The tragedy is so old, but even within it there are actors—some who’ve chosen resistance, and some, like West, who, however blithely, have chosen collaboration.

West might plead ignorance—“I don’t have all the answers that a celebrity is supposed to have,” he told Charlamagne. But no citizen claiming such a large portion of the public square as West can be granted reprieve. The planks of Trumpism are clear—the better banning of Muslims, the improved scapegoating of Latinos, the endorsement of racist conspiracy, the denialism of science, the cheering of economic charlatans, the urging on of barbarian cops and barbarian bosses, the cheering of torture, and the condemnation of whole countries. The pain of these policies is not equally distributed. Indeed the rule of Donald Trump is predicated on the infliction of maximum misery on West’s most ardent parishioners, the portions of America, the muck, that made the god Kanye possible.

And he is a god, though one born of a different time and a different need. Jackson rose in the last days of enigma and wonder; West, in an accessible age, when every fuck is a tweet and every defecation a status update. And perhaps, in that way, West has done something more remarkable, more amazing than Jackson, because he is a man of no mystery, overexposed, who holds the world’s attention through simply the consistent, amazing, near-peerless quality of his work.

He arrived to us with Bin Laden, on September 11, 2001—life emerging out of mass death—and I guess it is more accurate to say here that he arrived to me on that day, because West had been producing since at least five years before. All I know is when I heard his production on The Blueprint, I felt that he was the one I had been waiting for. I was then, still, an aesthetic conservative, a vulgar backpacker who truly and absurdly believed that shiny suits had broken the cypher, scratched the record, and killed my beloved hip-hop. My theme music alternated between Common’s “I Used to Love H.E.R.,” The Roots’ “What They Do,” and O.C.’s “Time’s Up.” Slick Rick’s admonition—“Their time’s limited, hard-rocks’ too”—was my mantra, so that on that day of mass murder, when Kanye West greeted me, chopping up the Jackson 5, drawing from Bobby “Blue” Bland, pulling from David Ruffin, arrived with Jay-Z, an MC who dated back to the Golden Age, I did not see myself simply in the presence of a great album, but bearing witness to the fulfillment of prophecy. This was insane, and it has been the great boon of my life that Twitter did not exist back then, to come of age in the last days of mystery, because Lord knows how many times I would have told you hip-hop was dead, and Lord knows how many times I would have said “Incarcerated Scarfaces” was the peak of civilization. Forgive me, but that is who I was, an old man before my time, and all I can say is that when I heard Kanye, I felt myself back in communion with something that I felt had been lost, a sense of ancestry in every sample, a sound that went back to the separated and unequal, that went back to the slave.

That was almost 20 years ago. It is easy to forget just how long West has been at this, that he’s been excellent for so long, that there are adults out there, now, who have never seen the sun set on the empire of Kanye West. And he made music for them, for the young and futuristic, not for the old and conservative like me, and so avoided the tempting rut of nostalgia, of soul samples and visions of what hip-hop had been. And so to those who had been toddlers in the era of The Blueprint, he became a god, by pulling from that generation raised in hip-hop’s golden age, and yet never being shackled by it. (Even after the events of the week, it would shock no one if West’s impending was the best of the year.)

West is 40 years old, a product of the Crack era and Reaganomic Years, a man who remembers the Challenger crash and The Cosby Show before syndication. But he never fell into the bitterness of his peers. He could not be found chasing ghosts, barking at Soulja Boy, hectoring Lil Yachty, and otherwise yelling at clouds. To his credit, West seemed to remember rappers having to defend their music as music against the withering fire of their elders. And so while, today, you find some of these same artists, once targets, adopting the sanctimonious pose of the arthritic jazz-men whom they vanquished, you will not find Yeezy among them, because Yeezy never got old.

Maybe that was the problem.

Everything is darker now and one is forced to conclude that an ethos of “light-skinned girls and some Kelly Rowlands,” of “mutts” and “thirty white bitches,” deserved more scrutiny, that the embrace of a slaveholder’s flag warranted more inquiry, that a blustering illiteracy should have given pause, that the telethon was not wholly born of keen insight, and the bumrushing of Taylor Swift was not solely righteous anger, but was something more spastic and troubling, evidence of an emerging theme—a paucity of wisdom, and more, a paucity of loved ones powerful enough to perform the most essential function of love itself, protecting the beloved from destruction.

I want to tell you a story about the time, still ongoing as of this writing, when I almost lost my mind. In the summer of 2015, I published a book, and in so doing, became the unlikely recipient of a mere fraction of the kind of celebrity Kanye West enjoys. It was small literary fame, not the kind of fame that accompanies Grammys and Oscars, and there may not have been a worse candidate for it. I was the second-youngest of seven children. My life had been inconsequential, if slightly amusing. I had never stood out for any particular reason, save my height, and even that was wasted on a lack of skills on the basketball court. But I learned to use this ordinariness to my advantage. I was a journalist. There was something soft and unthreatening about me that made people want to talk. And I had a capacity for disappearing into events and thus, in that way, reporting out a scene. At home, I built myself around ordinary things—family, friends, and community. I might never be a celebrated writer. But I was a good father, a good partner, a decent friend.

Fame fucked with all of that. I would show up to do my job, to report, and become, if not the scene, then part of it. I would take my wife out to lunch to discuss some weighty matter in our lives, and come home, only to learn that the couple next to us had covertly taken a photo and tweeted it out. The family dream of buying a home, finally achieved, became newsworthy. My kid’s Instagram account was scoured for relevant quotes. And when I moved to excise myself, to restrict access, this would only extend the story.

It was the oddest thing. I felt myself to be the same as I had always been, but everything around me was warping. My sense of myself as part of a community of black writers disintegrated before me. Writers, whom I loved, who had been mentors, claimed tokenism and betrayal. Writers, whom I knew personally, whom I felt to be comrades in struggle, took to Facebook and Twitter to announce my latest heresy. No one enjoys criticism, but by then I had taken my share. What was new was criticism that I felt to originate as much in what I had written, as how it had been received. One of my best friends, who worked in radio, came up with the idea of a funny self-deprecating segment about me and my weird snobbery. But when it aired, the piece was mostly concerned with this newfound fame, how it had changed me, and how it all left him feeling a type of way. I was unprepared. The work of writing had always been, for me, the work of enduring failure. It had never occurred to me that one would, too, have to work to endure success.

The incentives toward a grand ego were ever present. I was asked to speak on matters which my work evidenced no knowledge of. I was invited to do a speaking tour via private jet. I was asked to direct a music video. I began to understand how and why famous writers falter, because writing is hard and there are “writers” who only do that work because they have to. But it was now clear there was another way—a life of lectures, visiting-writer gigs, galas, prize committees. There were dark expectations. I remember going with a friend to visit an older black writer, an elder statesman. He sized me up and the first thing he said to me was, “You must be getting all the pussy now.”

What I felt, in all of this, was a profound sense of social isolation. I would walk into a room, knowing that some facsimile of me, some mix of interviews, book clubs, and private assessment, had preceded me. The loss of friends, of comrades, of community, was gut-wrenching. I grew skeptical and distant. I avoided group dinners. In conversation, I sized everyone up, convinced that they were trying to extract something from me. And this is where the paranoia began, because the vast majority of people were kind and normal. But I never knew when that would fail to be the case.

On top of the skewed incentives, the wrecked friendships, the paranoia, the ruin of community, there was a part of me that I was left to confront. I was the loneliest I’d ever felt in my life—and part of me loved it, loved the way I’d walk into a restaurant in New York and make the wait disappear, loved the random swag, the green Air Force Ones, the blue joggers. I loved the movie stars, rappers, and ballplayers who cited my work, and there was so much more out there waiting to be loved. I loved my small fame because, though I had brokered a peace with all my Baltimore ordinariness, with how I faded into a crowd, with how unremarkable I really was—and though I decided to till, as Emerson says, my own plot of ground, whole other acres now appeared before me. It almost didn’t matter whether I claimed those acres or not, because who are you if, even as you do good, you feel the desire to do evil? The terrible thing about that small fame was how it undressed me, stripped me of self-illusion, and showed how easily I could be swept away, how part of me wanted to be swept away, and even if no one ever saw it, even if I never acted on it, I now knew it, knew that I could love that small fame in the same terrible way that I want to live forever, in that way, to paraphrase Walcott, that drowned sailors loved the sea.

But I did not drown. I felt the gravity of that small fame, feel its gravity even now, and it revealed securities as sure as it did insecurities, reasons to preserve the peace. I really did love to write—the irreplaceable thrill of transforming a blank page, the search for the right word, like pieces of a puzzle, the surgery of stitching together odd paragraphs. I loved how it belonged to me, a private act of creation, a fact that dissipated the moment I stepped in front of a crowd. So, that really was me. But more importantly, I think, were things beyond me, the pre-fame web of connections around me—child, spouse, brothers, sisters, friends—the majority of whom held fast and remained.

What would I be both without that web and with a larger, more menacing fame? I think of Michael Jackson, whose father beat him and called him “big nose.” I think of the sad tale of West’s rumored stolen laptop. (“And as far as real friends, tell my cousins I love ‘em / Even the one that stole the laptop, you dirty motherfucker.”) I think of West confessing to an opioid addiction, which had its origins in his decision to get liposuction out of fear of being seen as fat. And I wonder what private pain would drive a man to turn to the same procedure that ultimately led to the death of his mother.

There’s nothing original in this tale and there’s ample evidence, beyond West, that humans were not built to withstand the weight of celebrity. But for black artists who rise to the heights of Jackson and West, the weight is more, because they come from communities in desperate need of champions. Kurt Cobain’s death was a great tragedy for his legions of fans. Tupac’s was a tragedy for an entire people. When brilliant black artists fall down on the stage, they don’t fall down alone. The story of West “drugged out,” as he put it, reduced by the media glare to liposuction, is not merely about how he feels about his body. It was that drugged-out West who appeared in that gaudy lobby, dead-eyed and blonde-haired, and by his very presence endorsed the agenda of Donald Trump.

I finally saw Michael Jackson moonwalk in 2001, finally watched the myth descend into the real, though finally overstates the matter. I had, by then of course, seen the legendary tape of his performance at Motown 25, but somehow it was not yet real to me, because I had not shared in the actual moment, at that moment, because I still, after all those years, remembered the longing of having missed a great event, and having experienced it secondhand. But this time I really was there, live as it was airing—the 30th anniversary of Jackson’s entrance into the pop-music world—and I am thankful that it happened then, at the end of that era of myth and legend, when the internet was still embryonic, and DVRs were not omnipresent, and the world had not yet been YouTubed, and reality television had just begun to peek over the horizon. This was a world still filled with the mysteries, secrets, and crank theories of my childhood, where the Klan manufactured tennis shoes and bottled iced tea, and shipped it all into the ghetto. What I am saying is that this was still a time, as in my childhood, when you mostly had to see things as they happened, and if you had not seen them that way, there still was a gnawing disbelief as to whether they had happened at all.

I think this, in part, explains the screaming and fainting. Jackson cranked up “Billie Jean” and I felt it too. For when I saw Michael Jackson glide across the stage that night at Madison Square Garden, mere days before the Twin Towers fell, I did not imagine him so much walking on the moon, as walking on water. And the moonwalk was the least of things. He whipped his mop of hair and, cuffing the mic, stomped with the drums, spun, grabbed the air. I was astounded. There was the matter of his face, which took me back to the self-hatred of the ’80s, but this seemed not to matter because I was watching a miracle—a man had been born to a people who controlled absolutely nothing, and yet had achieved absolute control over the thing that always mattered most—his body.

And then the song climaxed. He screamed and all the music fell away, save one solitary drum, and boneless Michael seemed to break away, until it was just him and that “Billie Jean” beat, carnal, ancestral. He rolled his shoulders, snaked to the ground, and then backed up, pop-locked, seemed to slow time itself, and I saw him pull away from his body, from the ravished face, which wanted to be white, and all that remained was the soul of him, the gift given onto him, carried in the drum.

I like to think I thought of Zora while watching Jackson. But if not, I am thinking of her now:

It was said, “He will serve us better if we bring him from Africa naked and thing-less.” So the bukra reasoned. They tore away his clothes so that Cuffy might bring nothing away, but Cuffy seized his drum and hid it in his skin under the skull bones. The shin-bones he bore openly, for he thought, “Who shall rob me of shin-bones when they see no drum?” So he laughed with cunning and said, “I, who am borne away, to become an orphan, carry my parents with me. For rhythm is she not my mother, and Drama is her man?” So he groaned aloud in the ships and hid his drum and laughed.

There is no separating the laughter from the groans, the drum from the slave ships, the tearing away of clothes, the being borne away, from the cunning need to hide all that made you human. And this is why the gift of black music, of black art, is unlike any other in America, because it is not simply a matter of singular talent, or even of tradition, or lineage, but of something more grand and monstrous. When Jackson sang and danced, when West samples or rhymes, they are tapping into a power formed under all the killing, all the beatings, all the rape and plunder that made America. The gift can never wholly belong to a singular artist, free of expectation and scrutiny, because the gift is no more solely theirs than the suffering that produced it. Michael Jackson did not invent the moonwalk. When West raps, “And I basically know now, we get racially profiled / Cuffed up and hosed down, pimped up and ho’d down,” the we is instructive.

What Kanye West seeks is what Michael Jackson sought—liberation from the dictates of that we. In his visit with West, the rapper T.I. was stunned to find that West, despite his endorsement of Trump, had never heard of the travel ban. “He don’t know the things that we know because he’s removed himself from society to a point where it don’t reach him,” T.I. said. West calls his struggle the right to be a “free thinker,” and he is, indeed, championing a kind of freedom—a white freedom, freedom without consequence, freedom without criticism, freedom to be proud and ignorant; freedom to profit off a people in one moment and abandon them in the next; a Stand Your Ground freedom, freedom without responsibility, without hard memory; a Monticello without slavery, a Confederate freedom, the freedom of John C. Calhoun, not the freedom of Harriet Tubman, which calls you to risk your own; not the freedom of Nat Turner, which calls you to give even more, but a conqueror’s freedom, freedom of the strong built on antipathy or indifference to the weak, the freedom of rape buttons, pussy grabbers, and fuck you anyway, bitch; freedom of oil and invisible wars, the freedom of suburbs drawn with red lines, the white freedom of Calabasas.

It would be nice if those who sought to use their talents as entrée into another realm would do so with the same care which they took in their craft. But the Gods are fickle and the history of this expectation is mixed. Stevie Wonder fought apartheid. James Brown endorsed a racist Nixon. There is a Ray Lewis for every Colin Kaepernick, an O.J. Simpson for every Jim Brown, or, more poignantly, just another Jim Brown. And we suffer for this, because we are connected. Michael Jackson did not just destroy his own face but endorsed the destruction of all those made in similar fashion.

The consequences of Kanye West’s unlettered view of America and its history are, if anything, more direct. For his fans, it is the quality of his art that ultimately matters, not his pronouncements. If his upcoming album is great, the dalliance with Trump will be prologue. If it’s bad, then it will be foreshadowing. In any case what will remain is this—West lending his imprimatur, as well as his Twitter platform of some 28 million people, to the racist rhetoric of the conservative movement. West’s thoughts are not original—the apocryphal Harriet Tubman quote and the notion that slavery was a “choice” echoes the ancient trope that slavery wasn’t that bad; the myth that blacks do not protest crime in their community is pure Giulianism; and West’s desire to “go to Charlottesville and talk to people on both sides” is an extension of Trump’s response to the catastrophe. These are not stray thoughts. They are the propaganda that justifies voter suppression, and feeds police brutality, and minimizes the murder of Heather Heyer. And Kanye West is now a mouthpiece for it.

It is the young people among the despised classes of America who will pay a price for this—the children parted from their parents at the border, the women warring to control the reproductive organs of their own bodies, the transgender soldier fighting for his job, the students who dare not return home for fear of a “travel ban,” which West is free to have never heard of. West, in his own way, will likely pay also for his thin definition of freedom, as opposed to one that experiences history, traditions, and struggle not as a burden, but as an anchor in a chaotic world.

It is often easier to choose the path of self-destruction when you don’t consider who you are taking along for the ride, to die drunk in the street if you experience the deprivation as your own, and not the deprivation of family, friends, and community. And maybe this, too, is naive, but I wonder how different his life might have been if Michael Jackson knew how much his truly black face was tied to all of our black faces, if he knew that when he destroyed himself, he was destroying part of us, too. I wonder if his life would have been different, would have been longer. And so for Kanye West, I wonder what he might be, if he could find himself back into connection, back to that place where he sought not a disconnected freedom of “I,” but a black freedom that called him back—back to the bone and drum, back to Chicago, back to Home.