Why More Philanthropists Are Giving Before They Die

The trend is a departure from the traditional model of donation—and could affect how large sums of money are put to use.

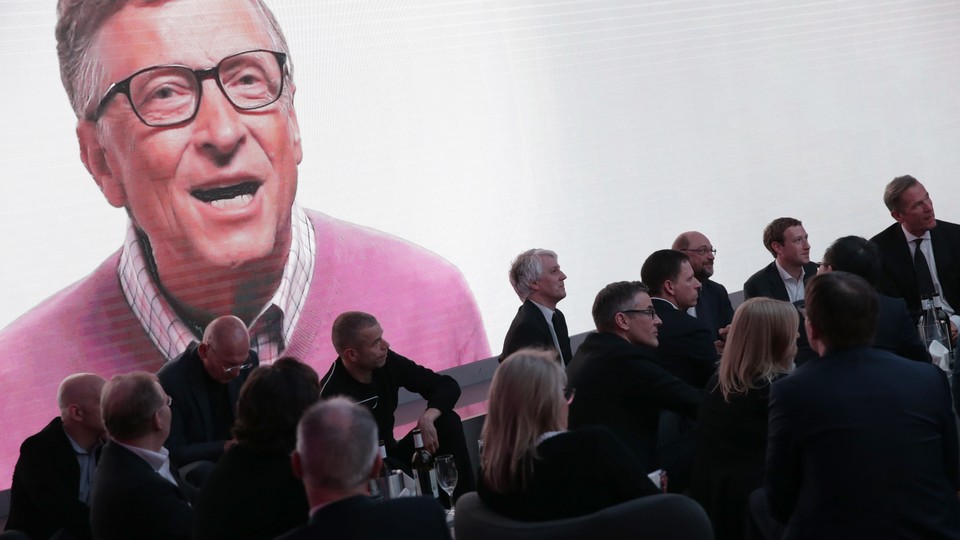

Big philanthropy is having something of a moment. There is the Giving Pledge, the promise made by more than a hundred of the United States’ wealthiest citizens, including Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, to give the vast majority of their fortunes to charity. Then there is the related “giving while living” movement, whose best known proponent is Charles Feeney, now 86, who has given away almost the entirety of his multi-billion dollar fortune during his lifetime.

Some, though, are cautious about these donations’ ultimate effects. There’s an argument that no matter how well intentioned, the scale of the money being directed toward philanthropic efforts by the wealthiest Americans is further contributing to an unequal balance of power in society, even as the givers claim that’s exactly what they are attempting to address.

Joel Fleishman knows these issues well. The director of the Center for Strategic Philanthropy and Civil Society at Duke University (and a professor there as well), Fleishman served for more than a decade as an executive at the Atlantic Philanthropies, the charitable foundation set up in 1982 by Feeney to carry out his own giving-while-living pledge.

Fleishman’s new book, Putting Wealth to Work: Philanthropy for Today or Investing for Tomorrow, is a survey of the world of charitable foundations, circa 2017. I recently spoke with him about philanthropic giving, including his surprising (for someone with his background) critique of giving while living, and strong defense of perpetual foundations, meaning foundations set up to continue on after their founders pass away. The conversation that follows is lightly edited and condensed for clarity and length.

Helaine Olen: What are the origins of the “giving while living” movement?

Joel Fleishman: Giving while living really originated with Andrew Carnegie. In a very famous document called "The Gospel of Wealth," which he published in 1888, he said you really should spend your money during your lifetime because if you do that, you'll be in a better position to be sure that it accomplishes what you hope. Of course, Andrew Carnegie didn’t, in the end, do that. He ended up with about a quarter of his fortune left at the point at which he was about to die which he still hadn't given away. He decided then to give it to a perpetual foundation, which he created. That’s now called the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

In our time, the person who is best known for giving while living is Chuck Feeney, the founder of Atlantic Philanthropies. The goal, the theory behind it, is that you could give away all of your assets during your lifetime and achieve much more. A lot of my book is about the question of how valid that assumption is.

Olen: And what do you think about that assumption?

Fleishman: If you say, “Can you achieve more in terms of diminishing hunger at present?,” I think you obviously can: If you give away a billion dollars to feed people, it's better than giving away 5 percent of a billion dollars annually. But if you're talking about curing cancer, it's a different story, because cancer is going to be cured, and indeed virtually every disease is going to be cured, by repetitive attempts to understand how cancer works and that requires hypotheses that are tested sequentially. You can't do it all at once.

My point here is that whether you can achieve significant impact really depends on what kind of problem you're trying to attack. The question is, do you care entirely about satisfying hunger or would you rather do something like figure out what's causing hunger in our system and trying to do something to correct those things that are perpetuating hunger or poverty?

Olen: But both approaches have their advantages, right?

Fleishman: Right. It’s clear that both kinds of philanthropy are needed. Solving social problems requires energetic persistence over time. It requires not only work by government, but it also requires a lot of other actors, like nonprofit organizations.

Look at the major nonprofit organizations that exist in the United States now. There are approximately 2 million nonprofit organizations that focus on a variety of problems, from the environment to race issues, to human rights, civil liberties, all those kind of things. And it has been primarily the perpetual foundations that were responsible for starting, nurturing, and indeed supporting many, if not most of the largest nonprofit organizations in the United States. As they say, Rome wasn't built in a day, and no public-policy problems have been solved in a day. The Green Revolution, for which Norman Borlaug of the Rockefeller Foundation earned a Nobel Peace Prize, took 35 to 40 years before they actually did develop the new grains that transformed countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh from chronically starving countries to chronically grain-exporting countries. It couldn’t be done in a short period of time.

I think those who have gone about this best are those that recognize that they cannot get instant impact on the problems that they care a lot about, in the short run. It just can't be done, because the problems don't lend themselves to it.

Olen: So if you are a philanthropist who wants to give while living, why set up a foundation? Couldn’t you just give the money to existing groups?

Fleishman: Most the people who are attracted to the idea of giving while living are attracted to the idea of getting some psychic satisfaction from what they do in the short run. Most major philanthropists who want to give away a lot of money are looking for a bigger bang. Most people who choose to give away a large amount of money during their lifetime are really wanting a more immediate sense of impact.

Olen: Is there a type of person who's more attracted to giving while living than others?

Fleishman: Most giving while living is done by people who have made a lot of money when they are young. My sense is that the reason is that they would like to replicate in the social sector the same level of achievement that they had in making their money in the for-profit sector. For example, look at the tech billionaires who are trying to figure out what to do with their money. They're not all motivated by a quest for instant impact, but many of them are. The more thoughtful people who want to give away a lot of money in the short run, they recognize the problems: There are constraints on their capacity to solve a problem in the short run, and they really need to support institutions like universities, like think tanks, that are working on these problems over the long run.

Olen: There is a critique that all this big-money philanthropy, no matter how well meant, is problematic: It’s allowing the wealthy to determine policy that is really the responsibility of an elected government. Do you think big philanthropy affords the giver too much power?

Fleishman: The United States has the First Amendment. The First Amendment is interpreted as not just about speaking out but also deploying your wealth on behalf of things that you care about. So, do these people have too much power? Under our Constitution, people are encouraged to spend their private resources to try to benefit society. And that tradition was one of the reasons that the United States has the largest amount of giving as a percentage of GDP of any country in the world.

Olen: But some of that giving is political.

Fleishman: If you read Jane Mayer's book Dark Money, you'll see how wealthy individuals can, in the case of the Koch Brothers, basically use nonprofit organizations to advance their political agendas. It's a very interesting book and it's very persuasive. One of the reasons that Trump’s support appears to be so widely spread around the country has to do, at least in part, with the fact that they have had these organizations there, these outposts of right, far-right, radical-right thinking.

Olen: Do you see similar moves on the left at all, or not to the same extent?

Fleishman: Not to the same extent. The left has not taken anywhere near as active a role. Only now is it starting to do that, and it has a lot of catching up to do. This is not something that happened instantly—it started with the creation of a number of explicitly right-leaning foundations, like the Olin Foundation, which I write about in my book. These foundations built the infrastructure.

Olen: This goes back to my question, though: Is this system giving too much power to the wealthy?

Fleishman: Well, the answer is we’ve never figured out whether it's a good idea to try to constrain the expenditure of funds for these kinds of things. And if we had to try to figure it out, it would be very complex to try to do that.

In Europe there's a long history of unwillingness to permit wealthy individuals and foundations to get involved in some areas of public policy, for the reasons that you are pointing out. My concern is that I cannot figure out how you are going to design laws and regulations that would in fact restrain people from spending the money on what they want to. And when you look at the record of the foundations over the course of the last century that they've been around, you have to say they’ve done a lot of very good things. There are many communities that continuously benefit from the existence of those foundations, locally—you don't hear any criticism from people in those towns about what the foundations are doing, nor do you hear much criticism from people around the country about what the big foundations are doing.

Ideologues can find anything they want wrong with the situation, but the fact is, government cannot do everything. We know about the fickleness of government and how it can change, as we've seen from going from Obama to Trump. So if you have more individuals who want to spend their wealth in ways that they think benefits society, I believe society benefits significantly from it.