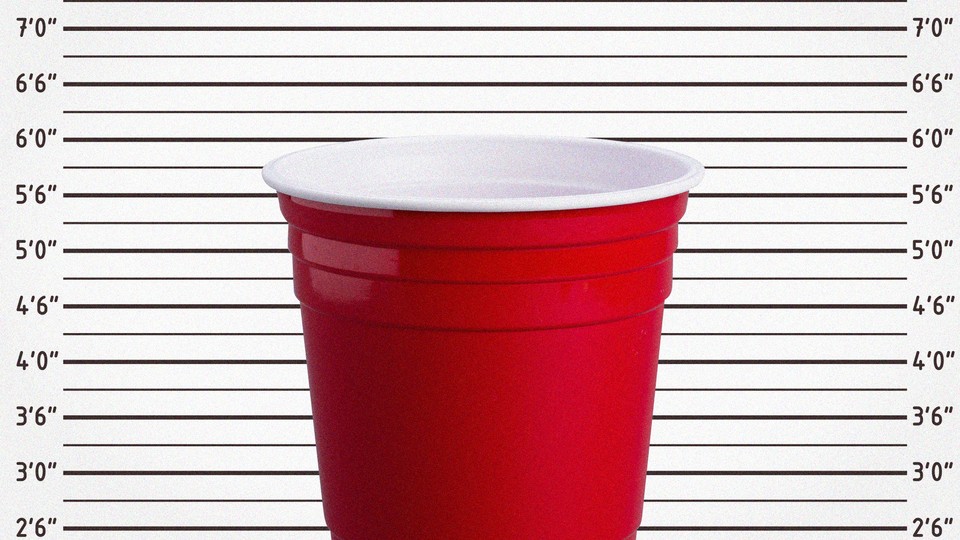

What's the Difference Between a Frat and a Gang?

They’re both blamed for predisposing their members to violent acts, but they’ve sparked radically different public-policy responses.

When I thought about locking up with a crew in 1996, I wanted to see a full initiation first, not parts I stumbled upon over the years. My friend Cliff and I arrived at a park not close from my home in Jamaica, Queens. Leaves danced with the wind around our feet, wafting an eerie feeling in my 14-year-old black body. The grounds of the initiation beckoned: a high-rise chain link fence, enclosing two basketball courts.

Through the daylighted chain, I watched scowls and punches and stomps engulf the uninitiated teen—a stoppage, then an awkward transition into hugs, handshakes, and smiles. The striking contrast shot at my core of authenticity, the insincerity of the punch-hug, of the stomp-smile, murdering my thoughts of joining a crew.

The same feeling shot within me five years later in 2001 when I thought about joining a college fraternity. The rumors of beatings and sexual assaults overwhelmed me like the worn-down bodies of pledges inching around campus unclothed in hazing. The before contrasted vividly again with the after: the excitable energy of the sparkling new brothers when they came out each year to the deafening cheers of their potential victims, especially in sororities. At these campus spectacles, my mind became a split screen of the past and the present.

My timeworn mind remains a split screen, seeing the fraternity from the same vantage point I see the gang. An abnormal view, I know. But from abnormal views, we discover.

The fraternity may be as violent as the gang. Collegiate America may be as dangerous for women as urban America. If sexual violence is a violent crime, then the fraternity of today may be committing as many violent crimes as the gang of the 1990s that spooked fearful Americans into tough-on-crime policies. The fraternity may be as frequently violent as the “savage gang MS-13,” as President Donald Trump called it in his State of the Union Address in January to spook fearful Americans into tough immigration policies. But Americans stereotype the gang and fraternity differently and treat them differently and rationalize their violence differently and police them differently. What if Americans looked at them similarly? What if Americans treated them similarly? What if Americans treated their victims similarly?

That is not to suggest that Americans should treat fraternities the same way they treat gangs right now any more than they should treat gangs the way they treat fraternities right now. But if experts on gang violence and sexual violence came together to extract the most effective policies and ideas from both, what lessons would they learn? Perhaps they would extract from the approach to the gang: the intense political will, the recognition of the crisis, the billions in public resources, the aggressiveness of investigators, the absolute refusal to blame the victims of violence, the centering of the victim. Perhaps they would extract from the approach to the fraternity: efforts focused on prevention and education, empathy for the accused, factoring in substance abuse, recognizing the causal complexity of human violence.

A call to bring together these experts may sound as outrageous as a call to conceptually bring together the gang and the fraternity. And yet, these calls are tuned by data and logic.

Five offenses are considered violent crimes in the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report Program: murder, non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault. But forcible rape is not the totality of sexual violence, according to the Center for Disease Control’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and the Division of Violence Prevention. Sexual violence includes “unwanted sexual contact”; “non-contact unwanted sexual experiences”; “alcohol/drug-facilitated penetration of a victim”; and “non-physically forced penetration which occurs after a person is pressured verbally or through intimidation or misuse of authority to consent or acquiesce.”

Fraternity men are not responsible for all, or probably not even most, of the sexual violence on college campuses these days. But the same was true of gangs and urban violence in the 1990s. Violent crimes in which the urban victim identified the offender as a gang member peaked in 1996 at 10 percent of all violent crimes, according to Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Still, gang culture has been linked to the violence problem. Gang members were found in one study to commit three times as many serious and violent offenses as non-gang youth. It is reasonable to conclude that gangs turned teens into people more likely to commit violent crimes.

Fraternity culture has been linked to the problem of sexual assault on college campuses, to recite a recent headline almost word for word. Three different studies found that frat men are three times more likely to rape than non-frat men. “It is reasonable to conclude that fraternities turn men into guys more likely to rape,” wrote the author of one of those studies.

In 1993, for every 1,000 urban residents, 74, or 7.4 percent, reported being victims of violent crime, a percentage that declined thereafter, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In 2016, for every 1,000 urban residents age 12 or older, 29.9, or 2.9 percent reported being victims of violent crimes, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In contrast, 16.9 percent of female freshmen reported being victims of non-consensual sexual contact by force and incapacitation during the 2014-15 academic year, according to a recent national survey of 27 universities. (Over the course of their collegiate life, 27.2 percent of senior women reported being victims of inappropriate sexual contact. Six of out 10 females, as well as gays and lesbians, reported “non-contact unwanted sexual experiences,” one of the CDC’s categories of sexual violence.)

A female freshman in college today may be more than two times more likely to be a victim of sexually violent contact than an urbanite was likely to be a victim of a violent crime in the mid-1990s. And, given the decline of violent crime in the intervening years, she may be more than five times more likely to face sexual violence on her campus than an urbanite is to face violence in her community. When “non-contact unwanted sexual experiences” are included, these disparities may be even larger.

Those numbers may be imprecise, or misleading. They may underestimate urban violence (and do not account for forms of “non-contact” urban violence). Sexual violence of all kinds is rampant off campuses, including in urban communities. And this comparison relies on the inexact science of self-reporting. I have been a victim of violent crimes, but never reported them to the police. More than half of the violent crimes from 2006 to 2010 went unreported to law enforcement, according to a report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics and RTI International. But underreporting may be even worse when it comes to sexual violence on college campuses. One 2000 study from the U.S. Department of Justice found that more than 95 percent of collegiate victims of completed or attempted rapes—let alone other forms of sexual violence—did not report the assaults.

No one really knows how often violence occurs in urban communities, or how often sexual violence occurs on (or off) college campuses. But I do know the perception of danger could not be more different. I do know societal perceptions and reactions to gangs and fraternities could not be more different.

[Readers respond: Is There a Difference Between a Frat and a Gang?]

Consider this series of contrasts: toughness toward savage gang boys versus softness toward immature frat men. Worries about destroying the lives of drunk 20-year-olds accused of violence versus hardly caring about destroying the lives of high 16-year-olds accused of violence. Attacking gangs wielding the faces of their victims versus attacking and defacing the victims of fraternities. Defending death sentences for violent gang boys versus defending the life of privileged denial for violent frat men.

This double standard is both racist and elitist. After all, the stereotypical gang boy is poor and non-white. The stereotypical frat man is elite and white. And the double standard is sexist, as well. A blinding toxicity of masculinity prevents some Americans from truly caring about the typical victim of sexual assault on college campuses in the way they care about the victim of urban violence. Then again, how many Americans really care about those mourning Latino parents of an MS-13 victim that Trump invited to his State of the Union Address? Or about urban Black teens like ‘90s me who were jumped or killed by gangs? And how many want to lock up, deport, or segregate as many of us as possible so we won’t harm them? Do most Americans think there is something wrong with the poor black gang boy and his non-white family, culture, community, and country that is not wrong with the family, culture, community, and country that produces the elite white frat man?

Gang boys are commonly cast as humanity’s problem; youth of color are demonized as super-predators. But frat boys apparently make stupid mistakes as all humans do; none of them, apparently, are super-preying on women.

This is not an attack on all American male gangs or fraternities, especially those healthy brothers and brotherhoods living in the shadows of the toxicity plaguing communities and campuses. It is an attack on Americans’ wildly disparate perceptions of, and policies towards, gangs and fraternities.

Three out of four major police departments already had new gang intelligence units (GIUs) by 1993. “Gangs and drugs have taken over our streets,” President Bill Clinton said as he signed the multi-billion dollar Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, the largest crime bill in American history, the next year.

Fraternities and sexual violence have taken over our colleges. And yet, has Congress ever seriously considered steering billions to thwart sexual violence, to clean up the toxic masculinity poisoning fraternities and campus life?

The task of addressing campus sexual violence has fallen primarily to colleges. But some colleges have been as reluctant to expose and subdue the sexual violence in their jurisdictions as police departments have been to expose and stamp out the police violence in their jurisdictions.

Hazing and discriminatory membership policies have prompted politicians and institutions like Florida State University and Harvard University to punish fraternities in recent years—not the preponderance of evidence of sexual violence. The Obama administration tried to push and prop up reluctant colleges. In 2011, the Office for Civil Rights urged campus officials to respond more promptly to reports of sexual violence, and use a less-rigorous standard for determining whether a sexual assault occurred.

But neither Democrats nor Republicans appear willing to declare political war on those sexually violent frat men in the way both declared political war on those violent gang boys in the 1990s, in the way Trumpian Republicans have declared political war on gangs today. “We cannot afford to be complacent in the face of violence that threatens too many of our communities,” said Attorney General Jeff Sessions on October 5 as he revived the war on gang violence. This resuscitation came two weeks after Education Secretary Betsy DeVos terminated the Obama-era fight against campus sexual violence. She revoked the more aggressive Obama-era guidelines for cracking down on campus sexual assault, claiming the federal overreach puts an undue burden on accused students to defend themselves. “The process … must be fair and impartial,” DeVos said.

DeVos appears more concerned with the rights of privileged men accused of sexual assaults than underprivileged boys in gangs being mass surveilled, suspected, and incarcerated. Sessions is federally overreaching on gang violence—not to mention on sanctuary cities and drugs—while DeVos is retracting the feds from deterring campus sexual violence. And they both work for a rich white man who relentlessly attacks gang violence, while relentlessly denying the accusations of sexual violence put forth by 22 women. Trump embodies the double standard and its multiple veins of bigotry.

Older frat men receive childlike compassion, teaching, and parental care away from home, while younger on average gang boys receive shame, charges as adults, and prisons away from home. Fraternities, surrounded by recruiters and breeders of politicians, aid their sexually violent members into jobs and wealth. Gangs, hounded by cops and highlighted by politicians, aid their violent members into penitentiaries and poverty.

Both models are failing in opposite directions to suppress the violence. Too punitive towards gangs. Too indulgent of frats. What about a new model that discards incarceration and indulgence as solvents? What about the split screen becoming one screen?

Instead America is stuck at the intersection of racism, sexism, and elitism as gangs and fraternities batter American bodies. How Americans carry on treating the violent and impoverished 16-year-old Latino gang member versus how Americans carry on treating the violent and affluent 21-year-old white fraternity brother—the split screen—should show us all about the self-destructive essence of American bigotry.